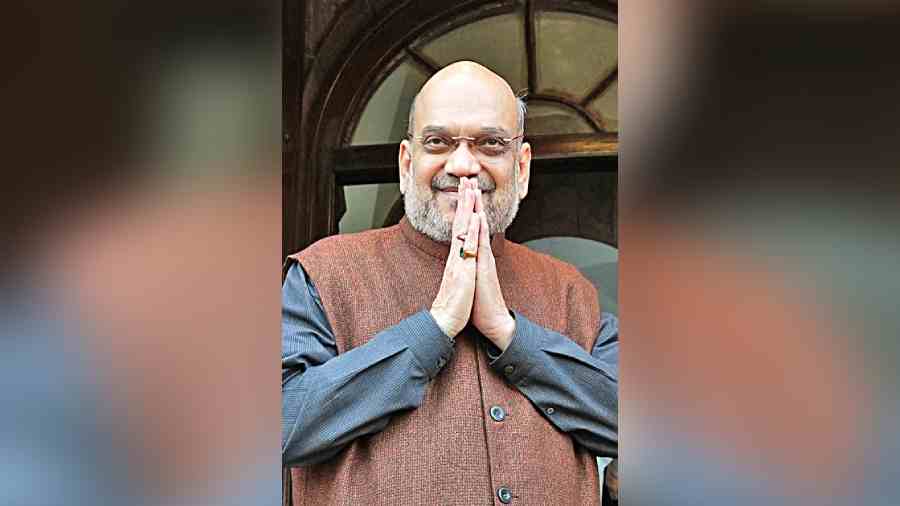

A senior Election Commission of India official on Friday said that nothing in Union home minister Amit Shah’s “permanent peace” speech in Gujarat had been found to violate the model code of conduct or any other law.

Shah had been quoted by the news agency PTI as saying in Gujarati at an election rally on November 25 that the BJP had “established permanent peace in Gujarat” in 2002 by teaching “a lesson” to those emboldened by the Congress to engage in rioting.

The poll panel official, who asked not to be named, said: “No community was mentioned in the speech, and hence it was not found to be violative.”

In 2002, Gujarat had witnessed an anti-Muslim pogrom after a train fire at Godhra railway station killed 59 kar sevaks returning from Ayodhya. The then state government, led by Narendra Modi as chief minister, was widely blamed for failing to control the violence.

At the rally in Mahuda, Shah was quoted as saying: “Through such riots, the Congress strengthened its vote bank and did injustice to a large section of society. But after they were taught a lesson in 2002, these elements left that path (of violence).

“They have refrained from indulging in violence from 2002 to 2022. The BJP has established permanent peace in Gujarat....”

No Congress leader was charged in the riots but several Sangh parivar sympathisers were convicted.

Former Congress MP Ehsan Jafri was brutally murdered during the riots in Ahmedabad.

Former Union economic affairs secretary E.A.S. Sarma and Jagdeep Chhokar, founder of the poll watchdog Association for Democratic Reforms, had complained to the commission about Shah’s speech.

Sarma wanted Shah’s statement to be examined for “appeal to caste or communal feelings for securing votes”. Chhokar alleged a violation of Section 8 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, and Section 153A of the Indian Penal Code that criminalises incitement.

The complainants are yet to receive a reply from the commission.

In a letter to the commission on December 2, Sarma had said: “I have tried scanning the website of the Election Commission of India (ECI) to ascertain whether the Commission has received and registered my two letters and whether it has taken any action. To my utmost disappointment, the Commission’s website makes no mention of the same, nor does it indicate the status of action.

“It is equally disappointing that I should gather information from news reports on the action said to have been taken by the Commission, the response of the Gujarat election authorities and so on.

“As a constitutional body, the ECI is a ‘public authority’ as defined in Section 2(h) of the Right to Information Act, 2005 (RTIA) and is required to make suo motu disclosures of important matters of public interest, as required in Section 4 of the RTIA.”

The Election Commission’s CVigil Portal — on which most complaints of model code of conduct (MCC) violations could be tracked during the 2019 polls — no longer offers such information.

It merely allows voters to lodge complaints and track their own plaints.

During the 2019 general election, complaints lodged against Prime Minister Narendra Modi stayed mysteriously invisible on the portal.

Then election commissioner Ashok Lavasa — who reportedly objected to the clean chits given to Modi and then BJP president Shah on complaints of poll code violations in 2019 — later quit to join the Asian Development Bank.

In its latest edition, CPM organ People’s Democracy said: “There is nothing to check the poisonous communal propaganda.

It has become normalised because of the failure of the Election Commission to intervene and act against repeated violations of the model code of conduct in previous Assembly elections and the Lok Sabha elections of 2019 when Narendra Modi and Amit Shah were the culprits.”

Low turnout

The commission’s current concern is the low voter turnouts in urban areas.

Almost all urban seats in Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh saw turnouts that were lower than before and below the state average.

“The old Systematic Voters’ Education and Electoral Participation (SVEEP) has reached its saturation point,” the commission official said.

“We will soon be unveiling a new SVEEP that reaches out to those who do not vote rather than repeatedly engaging those who already vote. Specifically, we want to reach out to migrants, city dwellers, the youth and those in the knowledge industry — which are segments of society where voting is perceived to be low.”

Currently, district officials implement the SVEEP through public advertisements and a whole range of events like bicycle rallies, dance programmes and recorded messages that play before telephone calls are placed. Often, local sponsors are involved.

The commission official said that more than half the electorate had now linked their voter cards with the Aadhaar system, which would help the poll panel identify voters who are registered in more than one place.