A police complaint by a Dalit woman has highlighted how the two perennial problems of water shortage and social discrimination combine to torment the rural poor in Bundelkhand every summer.

Sunita Devi, 40, has alleged that the affluent families of Kalupur village in Chitrakoot district, 250km south of Lucknow, are not allowing the poorer residents to use the government hand pumps amid the water crisis. She says she was beaten up when she tried to defy them.

“The village has five government-installed hand pumps, of which we were allowed to use only one for the last many years. But now, even that too is not for us,” she has said in her complaint.

“Till Thursday morning, the poor villagers were allowed to draw water from the lone hand pump. But the rich villagers stopped me today (Thursday) when I went to fetch drinking water for my family. Six people badly thrashed me when I said the pumps were meant for all.”

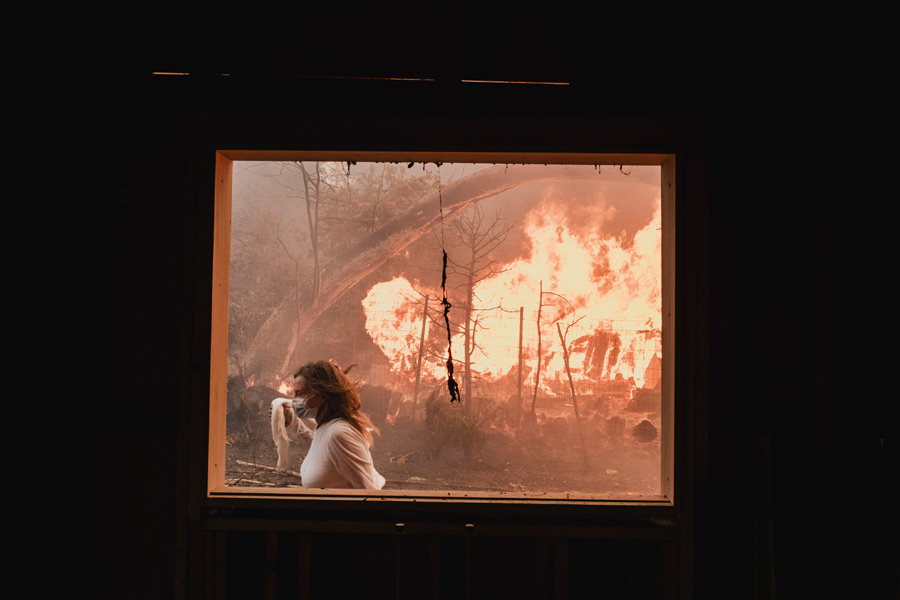

Sunita has sought police security. “The attackers said they would set me and my family on fire if I went to the police,” her complaint says.

Local people say such incidents are common in Chitrakoot every summer as most of the hand pumps either dry up or are appropriated by the affluent, who station guards before them or put a lock on them.

Anil Singh, the police inspector who received Sunita’s complaint, said he was probing the matter before registering an FIR.

“The woman, her husband Raju Kumar and son Durga Kumar had come to the police station. We are investigating the case and also trying to persuade the villagers not to guard or lock the hand pumps as they are meant for every villager.”

A report by the state panchayati raj department says that over 80 per cent of the 18,281 government-installed hand pumps in Chitrakoot, meant to cater to a population of 9.5 lakh, are either dry or need repairs.

Only the rich can afford private hand pumps, installing which costs Rs 1 lakh because the groundwater lies 20 metres under the hard, rocky soil even at the best of times.

For the poor like Sunita, the only option is to walk miles in the heat to the nearest natural source of water. However, even the rivers — Mandakini, Payaswani and Saryu — and the 1,300 ponds in the district tend to dry up during summer.

District magistrate Vishakh G. Iyer said the gram panchayat chiefs had been asked to make “alternative arrangements” — that is, arrange for government water tankers and ensure that every family gets a share.

“We are also doing re-boring and repair of the hand pumps. The funds have already been released,” Iyer told reporters.

Raju, Sunita’s husband, told reporters: “During summer, we worship a working hand pump as a god every day. But some people are keeping us away from our gods.”