The Jammu and Kashmir administration’s new media policy, which empowers the State to tell between fake news and authentic news and take action, has been criticised by almost all but one group: journalists’ associations in the Valley.

The silence has prompted suggestions that the strong tactics used by the administration, now headed by lieutenant governor G.C. Murmu, are working.

On June 2, the Union Territory’s administration had unveiled “Media Policy-2020” to examine what it called the content of print, electronic and other forms of media for “fake news, plagiarism and unethical or anti-national activities”.

The issue has repercussions outside Kashmir, too. “Fake news” is being used increasingly by oppressive regimes to not just spread lies but also give unpalatable reports a bad name and punish journalists.

When the phrase “fake news” began gaining currency, it was meant to describe deliberately fabricated reports that create an impression that the content is genuine, are usually spread over the Internet and are created to influence political views or to be treated as a joke.

However, of late, several governments have been construing honest mistakes as “fake news” and getting police to register FIRs and act against the journalist or media organisation concerned. Earlier, legal proceedings such as defamation cases used to be filed but only after the media outlet was given a chance to explain itself or correct its mistake if an error had been made.

The view from two sides of the spectrum in the US illustrates how the definition of “fake news” has been twisted out of shape.

In 2017, Michael Radutzky, the producer of CBS’s 60 Minutes, said: “We’re using the term ‘fake news’ to describe stories that are provably false, have enormous traction in the culture, and are consumed by millions of people.”

But President Donald Trump has broadened the meaning of “fake news” to include news that he finds hard to digest.

In Kashmir, politicians have described the new media policy as “undemocratic” and “colonial-era censorship” but no prominent journalists’ association in the Valley has so far protested in public.

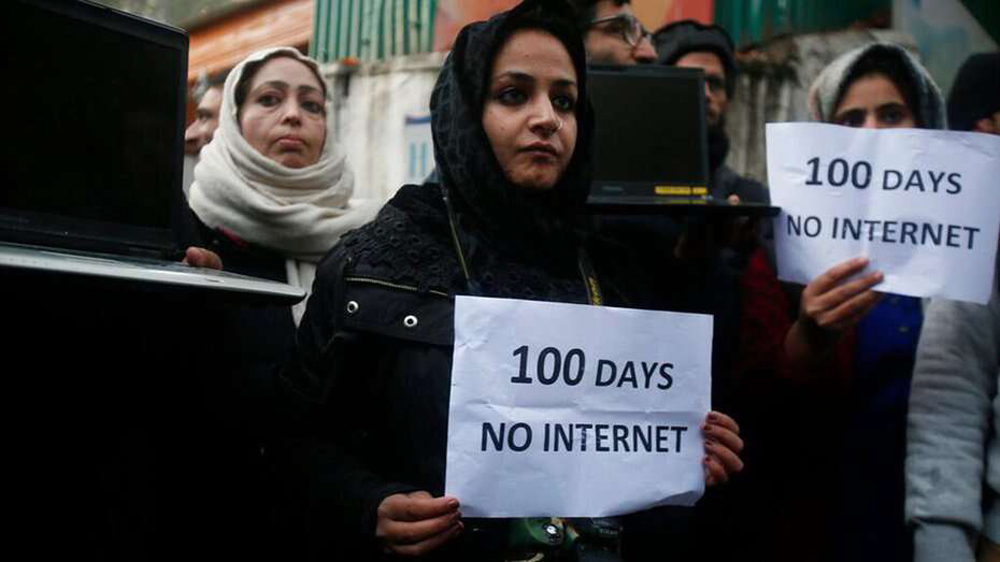

The new media policy has been announced amid a relentless clampdown that began with last year’s scrapping of Article 370. The administration intensified its crackdown against journalists by booking or summoning several of them to police stations. Two journalists — Masrat Zahra and Gowher Geelani — were booked under the draconian anti-terrorism act, UAPA, but were not arrested.

An editor with an English newspaper said the silence was deliberate and showed people were “scared” even months after the ball was set rolling on August 5 last year to scrap the then state’s special status.

Fearing retribution from the State or the freezing of government ads, many newspapers here have become the voice of the administration and resemble government bulletins.

“Some people did make efforts to oppose the new policy but later chose to be silent. Some people joke that if the J&K constitution was (not) given a damn, how does freedom of speech matter?” the editor told The Telegraph, requesting anonymity.

“That said, the new media policy will literally give a cop or a clerk in the information department the authority to decide what constitutes fake news,” he said.

Jammu and Kashmir had its own constitution under Article 370. While the Valley-based media largely fell in line after the August 5 clampdown, many local journalists working for national or international media organisations defied the odds and refused to budge.

The Valley’s biggest media body is the Kashmir Press Club. Its general secretary, Ishfaq Tantray, said the club had an online meeting on the subject where members felt that all media organisations, including journalists’ associations and editors in Jammu and Kashmir, should come together and “devise a joint mechanism to deal with the issue”.

He, however, conceded that no journalists’ body has so far formally reacted to the move.

Tantray said he personally felt the policy was a “serious threat to press freedom in Jammu and Kashmir” and gave “unbridled powers to the director, information, to decide what is news and what is fake news and sit on judgement”.

“A reading of the policy further reveals the government will decide what is fake, antisocial or anti-national news. But the most important part is that journalists would be prosecuted under the IPC and cyber laws. That means if the government is not happy with your story, it will term it ‘fake’ and register a case against you,” he said.

The 50-page policy says that any individual or group indulging in “fake news, unethical or anti-national activities or plagiarism” shall be “de-empanelled, besides being proceeded against under the law”.

“There shall be no release of advertisements to any media which incite or tends to incite violence, question sovereignty and the integrity of India or violate the accepted norms of public decency and behaviour,” the policy adds.

It also makes background checks on newspaper publishers, editors and key staff members mandatory before empanelling the media outlet for government advertisements. Security clearance has been made mandatory for a journalist before the award of the accreditation.

Political parties have expressed outrage at the policy although many of their leaders, who were arrested during the clampdown, were released after signing bonds that they would not question the scrapping of Article 370 and other decisions.

Former chief minister Omar Abdullah said the truth would be the biggest casualty of this “Orwellian order”, referring to the media policy.

“The policy seems to be a remnant of colonial-era censorship. It was that colonial experience of the founding fathers of the country that made them realise the crucial significance of the freedom of press,” Omar’s spokesperson Imran Nabi said in a statement.

PDP leader and former journalist Suhail Bukhari said the new media policy was a step towards demolishing democratic institutions.