Among the many events put into the shade by the outbreak of Covid-19 in India was the inauguration of a museum in Bellary in Karnataka. Most likely the only museum in India focused on the Stone Age, the Robert Bruce Foote Sanganakallu Archaeological Museum is dedicated to an Englishman.

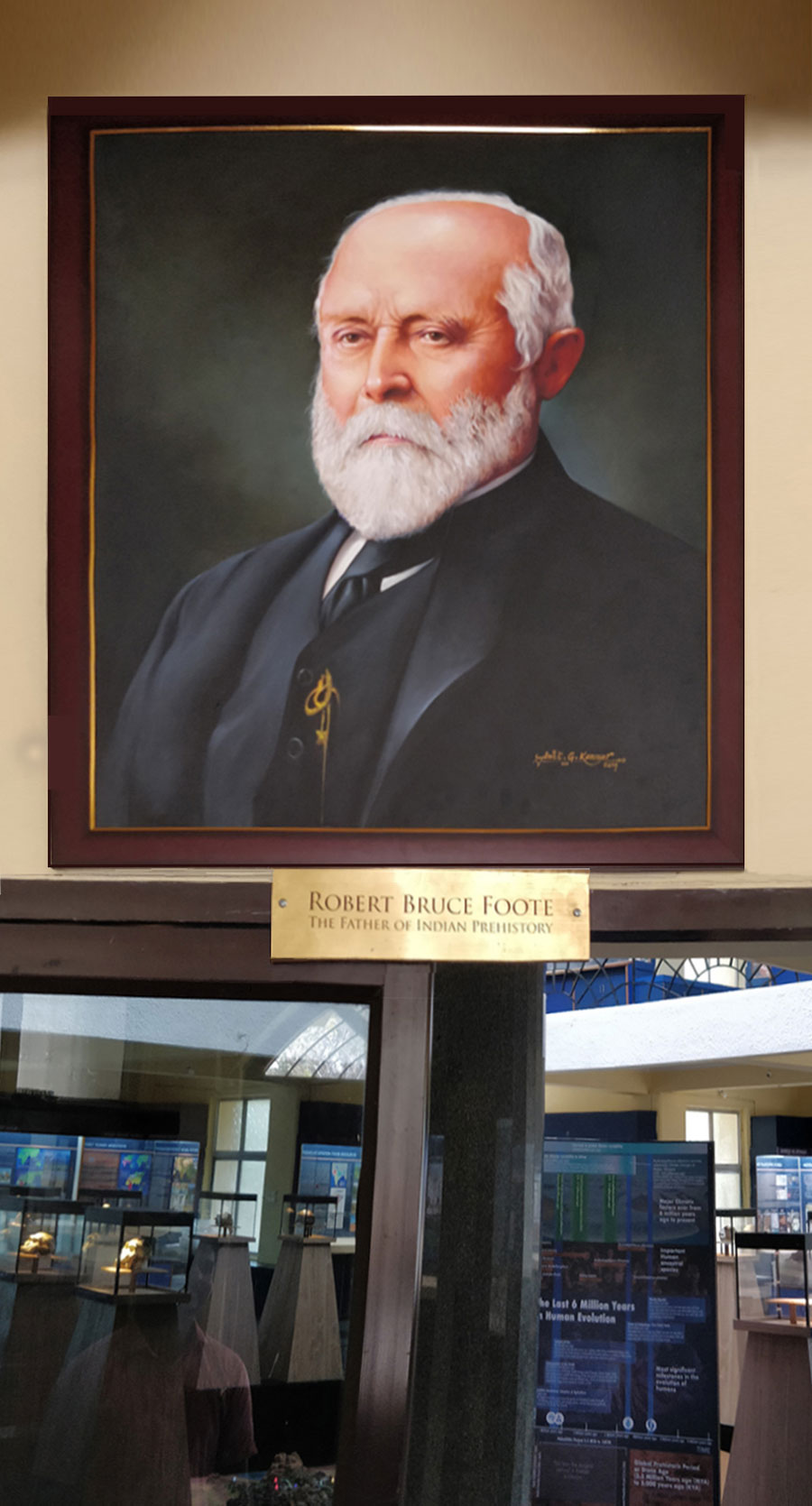

Robert Bruce Foote was a British geologist employed with the Geological Survey of India (GSI). Today, he is regarded as the father of south Indian geology, while archaeologists regard him as the father of Indian prehistory — a reference to the period before the invention of the alphabet or even the appearance of the first writings on stone surfaces.

The Englishman conducted his geological surveys between 1858 and 1891, and the greater part of his service was spent in south India — mostly in the Madras Presidency, which included Andhra Pradesh, parts of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Telangana, Odisha and Lakshadweep. In the Rayalaseema and Kalyana Karnataka regions — covering the whole of present-day northern Karnataka and western Andhra Pradesh — Foote had carried out detailed mapping of geological formations. But his interest went beyond minerals.

“He was a geologist with a passion for documenting evidence of prehistoric humans and their cultural evolution,” said the honorary director of the new museum, Ravi Korisettar, at a virtual talk organised recently by the Indian Museum in Calcutta. According to Korisettar, ever since his appointment by the GSI, Foote began his search for Early Man sites, especially in the Madras Presidency.

The Stone Age is divided into the Paleolithic (or Old Stone Age), Mesolithic (or Middle Stone Age) and Neolithic (or New Stone Age) periods. Megalithic is that which is typical of the period between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age. There are a large number of Paleolithic, Neolithic, Ashmound (typical of the Neolithic Age) as well as Megalithic sites not only in the Bellary region, where the museum stands, but also in Kurnool and Anantapur in Andhra Pradesh and Chitradurga in Karnataka.

Korisettar stresses on the importance of having a Stone Age museum and explains how an understanding of one’s past, even the remote past, is crucial to one’s sense of heritage. In the fitness of things, the new museum has initiated public outreach activity and archaeology workshops for museology students and schoolteachers, he tells The Telegraph.

The entrance to the Robert Bruce Foote Sanganakallu Archaeological Museum Sourced by the correspondent

In the preface to his 1901 work, Catalogue of the Prehistoric Antiquities, Foote writes how, ever since he had learnt about the English geologists who had discovered chipped flint instruments in the drift beds of the Somme river valley in northern France, he was convinced of “the necessity of looking out for possible similar traces of early human art in south India where my work then lay...”

Foote’s geological investigations helped generate the basic maps of geological resources, including the most productive gold fields, and in the identification of prehistoric sites. He discovered over 450 prehistoric sites in the Madras Presidency. In Bellary alone, in the heart of the Rayalaseema region, he discovered more than 160 sites. Says Korisettar, who is also a professor of archaeology at Karnataka University, “Among the several sites that he discovered, the Sanganakallu site, about seven kilometres northeast of Bellary, was of much importance.”

In Sanganakallu, Foote identified a large ground-stone axe workshop of the Neolithic Age, dating back to 3000 BC. Korisettar says, “He also discovered Lower Paleolithic sites at Pallavaram and Attirampakkam, which represent the Acheulean phase associated with the Homo erectus or archaic man’s expansion out of Africa.”

Large-scale granite quarrying in the region in the last 20 years has destroyed many of these sites. Korisettar says Sanganakallu too has sustained much damage.

This is what prompted a group of archaeologists to approach administrative officials of the region with the idea of a museum.

The museum, as it stands now, houses artefacts from the Palaeolithic period to the Iron Age; human and animal remains from various sites; plant remains, especially charred grains, from the Neolithic and Iron Age levels at Sanganakallu; beads and other objects of adornment; ritual and symbolic objects.

The ground floor has a section each on the African roots of humankind, the Indian subcontinent’s prehistory, the prehistory of Kalyana Karnataka, and the geological resources exploited by the Neolithic communities in the Rayalaseema region. A variety of stone tools of the Palaeolithic period too are on display. In the central sunken area of the ground floor the scale-down model of the Sanganakallu hill complex and various archaeological features associated with the site are highlighted.

A sarcophagus burial pot — recovered from the Kudatini ashmound on the Bellary-Hospet road and exhibited in the first-floor gallery — is one of the prize collections attesting the emergence of elites in the Early Iron Age of south India. The multi-legged, boat-shaped pot gestures at the rise of a complex society, wherein a certain section of people was given special burial, indicative of status. It was found to contain the remains of a seven-year-old.

Foote himself was cremated, after he died in Presidency Hospital in Calcutta in 1912. He left most of his collection to the Government Museum in Chennai for future researchers, while some have found their way into the Indian Museum in Calcutta via the GSI.

Among the many events put into the shade by the outbreak of Covid-19 in India was the inauguration of a museum in Bellary in Karnataka. Most likely the only museum in India focused on the Stone Age, the Robert Bruce Foote Sanganakallu Archaeological Museum is dedicated to an Englishman.

Robert Bruce Foote was a British geologist employed with the Geological Survey of India (GSI). Today, he is regarded as the father of south Indian geology, while archaeologists regard him as the father of Indian prehistory — a reference to the period before the invention of the alphabet or even the appearance of the first writings on stone surfaces.

The Englishman conducted his geological surveys between 1858 and 1891, and the greater part of his service was spent in south India — mostly in the Madras Presidency, which included Andhra Pradesh, parts of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Telangana, Odisha and Lakshadweep. In the Rayalaseema and Kalyana Karnataka regions — covering the whole of present-day northern Karnataka and western Andhra Pradesh — Foote had carried out detailed mapping of geological formations. But his interest went beyond minerals.

“He was a geologist with a passion for documenting evidence of prehistoric humans and their cultural evolution,” said the honorary director of the new museum, Ravi Korisettar, at a virtual talk organised recently by the Indian Museum in Calcutta. According to Korisettar, ever since his appointment by the GSI, Foote began his search for Early Man sites, especially in the Madras Presidency.

The Stone Age is divided into the Paleolithic (or Old Stone Age), Mesolithic (or Middle Stone Age) and Neolithic (or New Stone Age) periods. Megalithic is that which is typical of the period between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age. There are a large number of Paleolithic, Neolithic, Ashmound (typical of the Neolithic Age) as well as Megalithic sites not only in the Bellary region, where the museum stands, but also in Kurnool and Anantapur in Andhra Pradesh and Chitradurga in Karnataka.

Korisettar stresses on the importance of having a Stone Age museum and explains how an understanding of one’s past, even the remote past, is crucial to one’s sense of heritage. In the fitness of things, the new museum has initiated public outreach activity and archaeology workshops for museology students and schoolteachers, he tells The Telegraph.

In the preface to his 1901 work, Catalogue of the Prehistoric Antiquities, Foote writes how, ever since he had learnt about the English geologists who had discovered chipped flint instruments in the drift beds of the Somme river valley in northern France, he was convinced of “the necessity of looking out for possible similar traces of early human art in south India where my work then lay...”

Foote’s geological investigations helped generate the basic maps of geological resources, including the most productive gold fields, and in the identification of prehistoric sites. He discovered over 450 prehistoric sites in the Madras Presidency. In Bellary alone, in the heart of the Rayalaseema region, he discovered more than 160 sites. Says Korisettar, who is also a professor of archaeology at Karnataka University, “Among the several sites that he discovered, the Sanganakallu site, about seven kilometres northeast of Bellary, was of much importance.”

In Sanganakallu, Foote identified a large ground-stone axe workshop of the Neolithic Age, dating back to 3000 BC. Korisettar says, “He also discovered Lower Paleolithic sites at Pallavaram and Attirampakkam, which represent the Acheulean phase associated with the Homo erectus or archaic man’s expansion out of Africa.”

Foote’s portrait in the museum Sourced by the correspondent

Large-scale granite quarrying in the region in the last 20 years has destroyed many of these sites. Korisettar says Sanganakallu too has sustained much damage.

This is what prompted a group of archaeologists to approach administrative officials of the region with the idea of a museum.

The museum, as it stands now, houses artefacts from the Palaeolithic period to the Iron Age; human and animal remains from various sites; plant remains, especially charred grains, from the Neolithic and Iron Age levels at Sanganakallu; beads and other objects of adornment; ritual and symbolic objects.

The ground floor has a section each on the African roots of humankind, the Indian subcontinent’s prehistory, the prehistory of Kalyana Karnataka, and the geological resources exploited by the Neolithic communities in the Rayalaseema region. A variety of stone tools of the Palaeolithic period too are on display. In the central sunken area of the ground floor the scale-down model of the Sanganakallu hill complex and various archaeological features associated with the site are highlighted.

A sarcophagus burial pot — recovered from the Kudatini ashmound on the Bellary-Hospet road and exhibited in the first-floor gallery — is one of the prize collections attesting the emergence of elites in the Early Iron Age of south India. The multi-legged, boat-shaped pot gestures at the rise of a complex society, wherein a certain section of people was given special burial, indicative of status. It was found to contain the remains of a seven-year-old.

Foote himself was cremated, after he died in Presidency Hospital in Calcutta in 1912. He left most of his collection to the Government Museum in Chennai for future researchers, while some have found their way into the Indian Museum in Calcutta via the GSI.