Thirty-five-forty kilometres from the historic battlefield of Plassey, a battle-worn general has been toiling 16, sometimes 18, hours a day to save his fortress, to ensure this general election in Behrampore does not end up being his Waterloo.

Rallies, road-shows, street corners, door-to-door visits.... A visibly exhausted Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury — the “Nawab of Murshidabad” to his detractors — has left no outreach method untried this merciless summer to woo his electorate, which has never handed him defeat in 20 years.

Since the polls were announced, he rarely left the constituency, and even gave party chief Rahul Gandhi’s Raiganj rally a miss, to focus on his own campaign. Those familiar with his methods say Chowdhury, now 63, has never had to invest this much effort in his own campaign.

Despite the characteristic flamboyance, that’s not faded with the ravages of time and many a recent setback, Chowdhury appears aware of this being his toughest challenge since he entered electoral politics as a 40-year-old livewire — having cut his teeth in politics with the RSP — in 1996, when he became the Nabagram MLA.

On an overcast evening in the middle of the Hareknagar marketplace, a sharply dressed Chowdhury, in spotless white, was seen braving a dust storm to campaign in his inimitable style, a spirited, no-holds-barred attack on Mamata Banerjee.

Speaking to this newspaper on the sidelines, Chowdhury said he was confident of “wiping out” Trinamul Congress in the district — the other two seats, Murshidabad and Jangipur, voted on April 23 — but issued a rider.

“If there are adequate central forces and are properly utilised, there is no stopping us…. If, however, the polls are compromised, no forecast can hold,” said Chowdhury, in the middle of obliging requests for selfies from hundreds. A close aide said Chowdhury was banking heavily on uncompromised electioneering in at least 1,700 of the seat’s 1,844 booths, for which the Election Commission has promised cent per cent central forces coverage.

To anybody who has met Chowdhury in campaign situations in the past, this is a marked shift. He is not in the habit of issuing riders while speaking of victory.

“The growth of Trinamul in this district was not organic and was achieved through defections by traitors. The defectors and their camps are yet to face genuine elections…. When they do, the results will surprise everyone. Everyone except me,” said the Congress’s go-to guy in Bengal for years, until his decline since 2016 was engineered by Mamata’s trusted lieutenant Suvendu Adhikari.

Mamata, who conducted three rallies in the constituency, and Adhikari have turned Behrampore — a town developed and fortified by the East India Company as a cantonment after the Battle of Plassey — into a battle for prestige.

Trinamul’s Apurba Sarkar campaigns in Beldanga. Picture by Chayan Majumdar

The odds are now stacked heavily against Chowdhury, with the fiercest challenge coming from his former protégé — whom he used to call his brother — Apurba Sarkar. The Congress’s three-term Kandi MLA defected to Trinamul last year and is Trinamul’s Behrampore candidate.

Sarkar is better known as David. The biblical reference is not lost on him.

“This being Murshidabad, he (Chowdhury) likes making Plassey references, imagining himself as Siraj ud-Daulah and his rivals as Mir Jafar or Robert Clive…. This time, the battle takes us far back from 1757. It’s David and Goliath. We know how that story goes,” said the 54-year-old, who managed Chowdhury’s campaign even in 2014.

Chowdhury’s plight in the face of a marauding Trinamul in Behrampore, now conspicuously wrapped in Sarkar’s campaign material, mirrors that of the besieged Siraj.

According to a former loyalist, there are several factors pitted against Chowdhury.

“Adhir has lost the people close to him, like David. He cannot mobilise funding. The administration has turned against him. His organisational strength has decayed. And he faces a significant split in the minority vote bank that used to see him through,” he said.

Adhikari, camping in the district for weeks and leaving no stone unturned to wrest the seat, oozed confidence.

“I see no challenge. That man (Chowdhury) is finished,” he said, ruling out the possibility of any difference from the discontent over alleged malpractice by his party in the panchayat polls of 2018.

“It’s an outright lie being peddled as an excuse for his own decline,” he added.

Political scientists said a major weakness of Chowdhury was the waning of the client-patron relationship he had established with his electorate and the strengthening of that between Mamata and the people in his backyard.

“Virtually every household now has multiple beneficiaries of the state government’s schemes. It is made clear that for getting the benefits, voting for Trinamul is a must,” said Biswanath Chakraborty, professor of political science at Rabindra Bharati University.

“Now Mamata is the patron. The voters remain the clients. The election is the time for payback…. This is biggest hurdle for the former patron, for Adhir,” he added.

But all might not be lost yet for Chowdhury, the only one of the state’s Congress MPs who impressed Rahul last month with his confidence in victory even in the absence of a truck with the Left.

The contest of 2014 was not deemed easy either and Mamata had heavily backed singer-turned-politician Indranil Sen against him. Sen, now a member of the Mamata cabinet, was handed a drubbing by Chowdhury, who secured 50.54 per cent votes against Sen’s 19.69 per cent. Chowdhury’s victory margin of 3,56,567 votes was the highest in Bengal.

Not unlike A.B.A. Ghani Khan Chowdhury in adjoining Malda, although on a much smaller scale, there is a lasting myth surrounding Chowdhury, for all he has done for his people. Over decades, he has been there for those in need, during floods, for weddings, for higher studies, for jobs.

Chowdhury’s image as a “Robin Hood-esque” fighter continues to be admired in the minority-dominated, backward district.

Besides, Chowdhury has the advantage of Behrampore being a virtually two-cornered fight this time, between him and Sarkar.

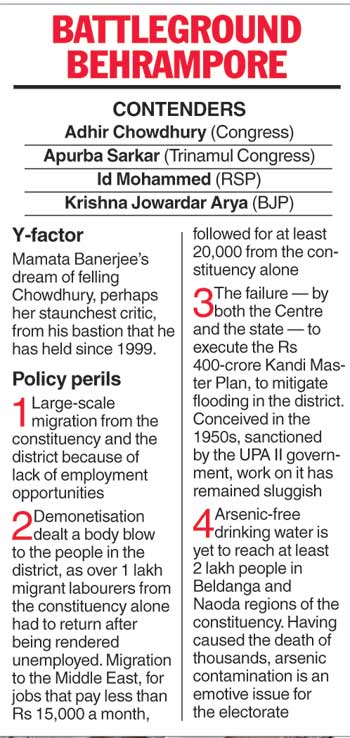

The BJP’s Krishna Jowardar Arya — a rank outsider who was BJP state unit chief Dilip Ghosh’s family priest — and the RSP’s Id Mohammed are also in the fray.

But the CPM, given its fondness for Chowdhury’s searing anti-Mamata activism, has disowned Mohammed and has been actively campaigning for Congress. With the backing of the Marxists, Chowdhury could well end up getting a healthy slice of the 19.54 per cent votes the Left secured in 2014.

There are also murmurs — and loud allegations from Mamata — that the saffron camp is backing Chowdhury in the seat, which has over 52 per cent minority voters. The BJP, a force to reckon with in Behrampore in the 1990s, has not managed more than seven per cent of the vote share in the past three elections.

Although Chowdhury’s image took a beating in the panchayat polls last year, when Adhikari ensured 64 per cent Murshidabad seats went uncontested and the few that saw contest were won by Trinamul through alleged fear or favour, it could have worked to his advantage.

Having lost much control to Trinamul in his former fief, if Chowdhury remains optimistic, it’s because is aware of the deep-seated angst in the people against the ruling party’s alleged excesses last summer.

“If the polls are free and fair — peaceful polling in this district is but a pipe dream — I will vote for Dada. Everyone I know will too,” said Jaminur Rahaman, a 30-year-old history honours graduate from Kalyani University, in Kandi’s Hatpara.

Seated in an abandoned makeshift office of Trinamul, Rahaman and his friends spoke of Dada, not Didi.

Rahaman tried and failed to get his dream job as a schoolteacher. He and his wife Tonifa Khatun, also a graduate, give private tuitions to sustain their family on Rs 10,000-odd.

“The right to vote being stolen means a lot to people here,” he said, sitting below a faded picture of a smiling Mamata.

“Murshidabad had fallen to Trinamul. But last summer.... It brought Dada back,” he added, his friends nodding in agreement.

Hushed echoes of such voices are heard in all corners of Behrampore’s seven Assembly segments — Kandi, Burwan, Bharatpur, Rejinagar, Beldanga, Naoda and Behrampore. But whether they are in majority among the seat’s 16,36,461 voters and will endorse their Dada en masse on Monday can only be known on May 23.

Behrampore votes on April 29