Tasmida wrote “Myanmar” in the column for nationality on her application form for the senior secondary exams of the Jamia Millia Islamia board here. The receipt for the application came with “Indian” printed on it.

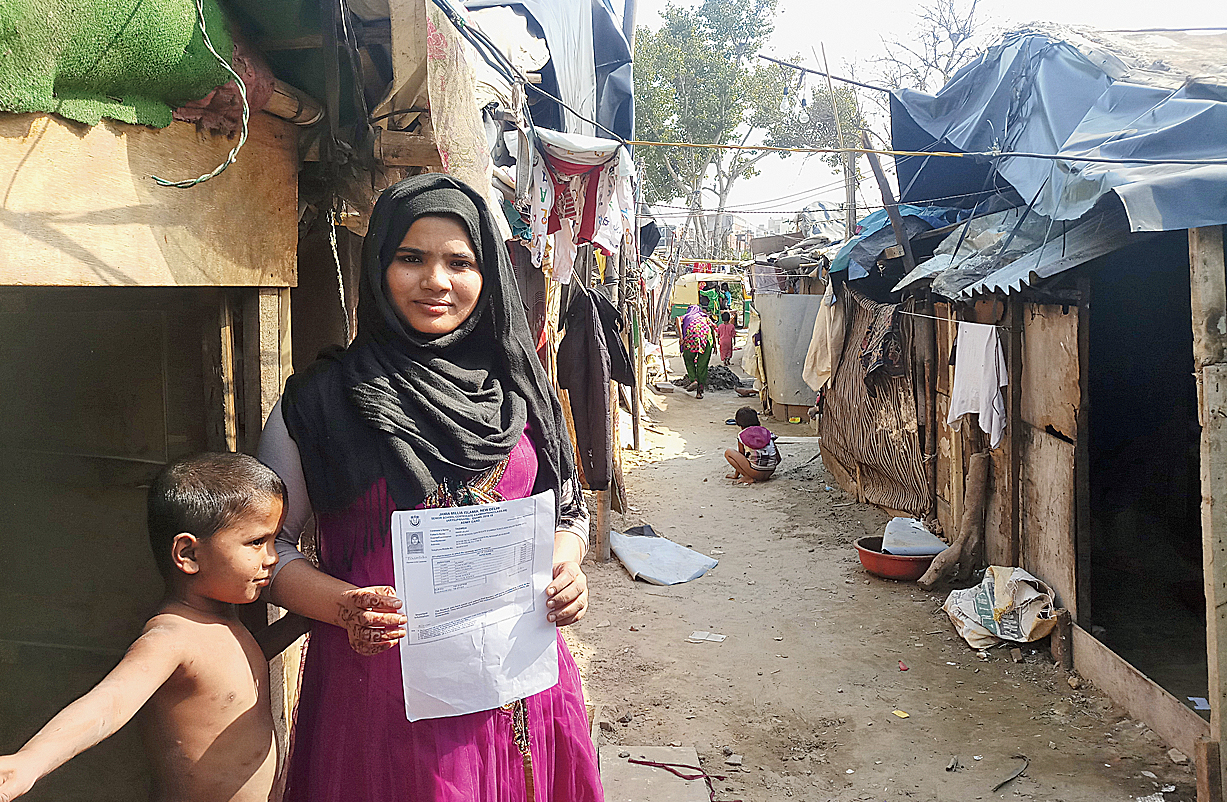

“I told my teacher and she asked me to submit the form again. The second time too the receipt showed ‘Indian’,” the 21-year-old Rohingya told The Telegraph at her tin-and-bamboo hut in a slum on the Yamuna’s banks here.

“My classmates told me that I’m an Indian now because I look Indian and speak Hindi. But I’m from Myanmar. I want my nationality.”

Tasmida is the first female candidate for the Class XII exams from the Rohingya refugee community in India.

The journey from Class III to Class XII has taken her 14 years, four schools, and the challenge of learning three languages from scratch — courtesy her family’s double immigration, from Myanmar to Bangladesh and then to India.

“When I was younger I didn’t know what ‘nationality’ means. But today, when I see how my friends can call India their own country, I too want to have my nationality of Myanmar,” she said.

Of the more than seven lakh Rohingya who have fled ethnic conflict in Myanmar, 17,500 —including Tasmida’s family — had got registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in India till last year. The UNHCR provides a semblance of security against deportation.

The Centre had told the Rajya Sabha in 2017 that it estimated that India had about 40,000 Rohingya refugees.

Community leaders say that hundreds have fled to Bangladesh following attacks by zealots and deportations over the past year.

The Rohingya Literacy Programme, headed by Tasmida’s brother and UNHCR translator Ali Johar, has counted only 40 Rohingya children in India currently enrolled in educational institutions.

Tasmida has submitted her form a third time with a copy of her birth certificate from Myanmar, her UNHCR refugee registration card (valid till 2020), and a copy of her long-term visa, which expired in 2015.

The slum in Kanchan Kunj where she lives with 53 other Rohingya families — after the nearby slum where she previously lived got burnt down — is on a part of the Yamuna’s flood plain where the Uttar Pradesh irrigation department has a huge billboard warning against encroachment.

Tasmida’s father Aman Ullah was a businessman who ran a boat service from Buthidaung, where the family lived in Myanmar, down the Mayu river to Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine state.

He also owned two trucks, a hotel and one of the only two telephones in Buthidaung until he fled to Bangladesh with his wife, six sons and Tasmida in 2005.

“The (Myanmarese) army or the police would regularly lock up my father and extort money from him before releasing him. I was in Class III then, and was seven years old,” Tasmida said.

“We drove to the border in a car and crossed over by boat. We settled down in a rented home in Cox’s Bazar. I did not know a word of Bangla as I had only studied in the Burmese medium and spoke Rohingya at home.”

She initially learnt to write her name in Bangla — the qualification required to enrol in a government school in Cox’s Bazar, where she was able to finish primary school by 2011.

“I used to sit with my books all day and kept reading whatever words I had learned till I understood everything.”

Tasmida joined a private institution — the Uttaran Model School and College — in Class VI. The riots in Rakhine that killed more than 160 people and led to thousands of Rohingya fleeing their homes happened the following year.

“With so many Rohingya everywhere, the Bangladesh authorities became strict. My father was picked up by the police on suspicion once. I had a birth certificate from my school but my parents had no papers,” she said.

“We decided to join my brother Abdullah, who had moved to Delhi with his in-laws. By then I knew Bangla well, but I had to drop out of school just before my annual exams.”

That year, 2012, the family travelled on a bus from Chittagong to the India-Bangladesh border somewhere close to Calcutta and walked across with local guides. They took a train to Delhi and settled down in a tent opposite the UNHCR office.

But no school in Delhi that her parents could afford would admit an undocumented immigrant with no knowledge of Hindi.

“We moved to Vikaspuri (west Delhi), where I learnt Hindi and English at the UNHCR (Reception and Registration) Centre. They helped me enrol in the National Institute of Open Schooling, from where I finished Class X in 2016,” she said.

The family eventually moved to Kanchan Kunj, where Tasmida’s parents now run a grocery at their slum.

“I dropped out of school for a while in 2015 because the neighbours would taunt us, asking why a refugee girl needed to study when she would get married anyway. But I resumed studying in six months after my parents asked me not to bother about what people say. Now all the young children here (in the slum) are studying,” she said.

Government schools near the Kanchan Kunj slum had refused her admission on various grounds. Tasmida was finally admitted to a charitable school in Okhla, the Centre for Women’s Condensed Course, which is affiliated to Jamia’s senior secondary board.

“I struggled with Hindi but the teachers were a great help. It’s difficult to study here (in the slum) because of the noise, mosquitoes and flies,” she said, as music blared from a wedding party next door.

The Rohingya Literacy Programme now runs a hostel nearby, supported by donations, where a dozen students live and several others, including Tasmida, come to study away from the noise of the streets.

Tasmida wants to study political science or English in college, and law after that.

Ask her why, and she says: “Kyunki mujhe awaz uthana hai (Because I want to raise my voice). I want to become a human rights activist. Our people are in so much trouble…. We are grateful to those who speak for us but it is better if we can speak for ourselves. If I study, other young people would feel inspired and begin to study.”

Now, in the middle of her exams, Tasmida is doing the rounds of the NIOS and a police station to get a copy of her Class X mark sheet, which was charred when her slum burnt down last year.

She doesn’t dwell on her misfortunes, though. “Everyone has problems. When God closes one door, he opens 10 windows,” she said.