Indian scientists have recovered from a site in Madhya Pradesh the fossilised remains of a giant extinct reptile called a phytosaur, a new species previously unknown to science but from the family of the oldest ancestors of modern-day crocodiles.

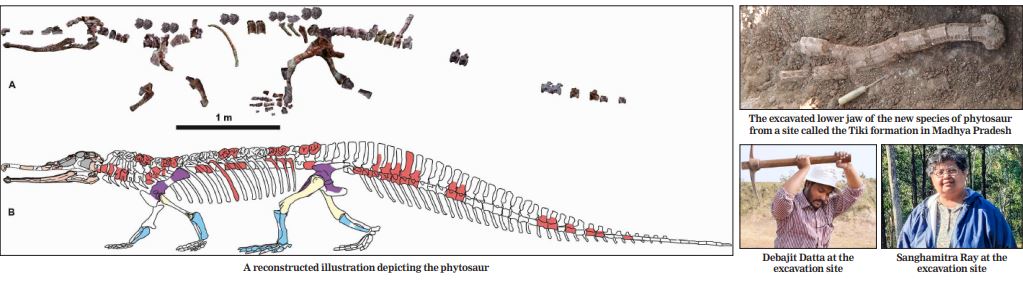

The researchers have assembled the skeletal remains of an eight-metre-long phytosaur from a set of bone fragments found embedded in mudstone layers dated between 231 million and 212 million years old, about 200km east of Khajuraho.

Fossil hunters have catalogued dozens of phytosaurs from various sites in North America, Europe, China and Morocco since German palaeontologist George Friedrich Jaeger reported the first one in 1828. An Indian palaeontologist Sankar Chatterjee had also described a phytosaur from Telangana in 1978.

Now, palaeontologist Sanghamitra Ray at the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, and research scholar Debajit Datta have described a new phytosaur with distinctive anatomical features that the scientists say was indigenous to the Indian subcontinent.

“An indigenous phytosaur would be something akin to the Asiatic lion, which is unique to India,” Datta said.

The scientists have named the phytosaur Colossosuchus techniensis, the first name representing its large size, the second intended to honour IIT Kharagpur, the institution that provided the platform for their research. They have published their findings in the journal, Papers in Palaeontology.

They found over 1,000 fossilised bone fragments from 21 individual phytosaurs, but most were juvenile bones and only four adults. Such a distribution of juvenile-adult bones from a single site, the scientists say, provides the first evidence from anywhere for parental care among phytosaurs.

“The evidence for parental care in these primitive reptiles was a surprise,” said Ray, professor of geology and geophysics at IIT, Kharagpur, who has led multiple fossil hunting expeditions in central India for over a decade. “We’ve known about parental care in dinosaurs, but they came much later.”

The largest adult phytosaur they have excavated from the geological site called the Tiki formation is over eight metres long, bigger than the average of two to four metres for most phytosaurs. And it has skeletal features not observed in other phytosaurs.

The bones from 21 individuals at a single site could have been the result of mass mortality caused by an infection, Ray and Datta and their collaborator Debarati Mukherjee at the Indian Statistical Institute, Calcutta, had speculated in a previous research paper in 2020.

The scientists, in an attempt to find a place for the new Indian phytosaur on the global family tree of phytosaurs, have discovered evidence for what they say was a mini-extinction event between 225 million and 228 million years ago in which primitive phytosaurs gave way to advanced phytosaurs.

“We’ve known that all phytosaurs disappeared from the Earth about 200 million years ago,” said Datta, currently a scientist at IIT, Roorkee. “But our analysis suggests that before that major extinction event, the primitive phytosaurs died out and were replaced by evolved advanced phytosaurs. The exact mechanisms underlying this mini-extinction remain unknown.”