March 29, Wednesday, 9.06pm

Tucked away at the end of a report despatched to The Telegraph, the newspaper I work for, a paragraph quotes Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee as saying on the eve of Ram Navami: “We will not stop any Ram Navami procession. But remember, Ramazan is on.... Everybody has the right to bring out processions or conduct rallies. Nobody has the right to instigate riots.”

“Uttishthata, jagrata,” I smirk and slot the paragraph for a brief mention in the newspaper.

Bad error of judgement.

The statement by the chief minister would come to define what should have been a superlative week for believers: the biggest confluence of the holiest calendars of three of the great religions on the planet. In the next 10 days or so, Hindus would celebrate Ram Navami and Hanuman Jayanti, Muslims would be passing through a part of the Ramazan month and Christians would complete Lent that would culminate in Good Friday and Easter.

A remarkable coincidence. The glorious serendipities that mischievous stars visit upon lesser mortals down below to test the highest callings that are supposed to drive human endeavour.

March 30, Thursday, Ram Navami

Reports trickle in of a clash in Howrah over Ram Navami. Several vehicles and shops have been torched or vandalised, police sources tell reporters.

From elsewhere in India, reports of “sporadic incidents” pop up on my phone screen: Aurangabad and Malad, Maharashtra; Lakhisarai, Nalanda and Kishanganj, Bihar; Khandwa and Khargone, Madhya Pradesh; Balidih and Dhanbad, Jharkhand; Vadodara (multiple incidents), Gujarat; Mathura, Uttar Pradesh; Jammu City, Jammu and Kashmir; Hyderabad, Telangana....

What was a brief mention a day earlier is taking a life of its own and metamorphosing into a beast that rears its head when elections hove into view.

Late into the night, after the printing presses have started rolling, I am pacing up and down a room at my home in south Calcutta. It is around 3.55am.

“Jai Shri Ram,” the voice carries amid the silence of the graveyard hour and fades.

I have heard this voice before but not of late. Then it clicks into place. This is a milkman who cycles past my home, near a temple that sits on the sidewalk. “Jai Shri Ram” is his salutation to the deity in the small shrine.

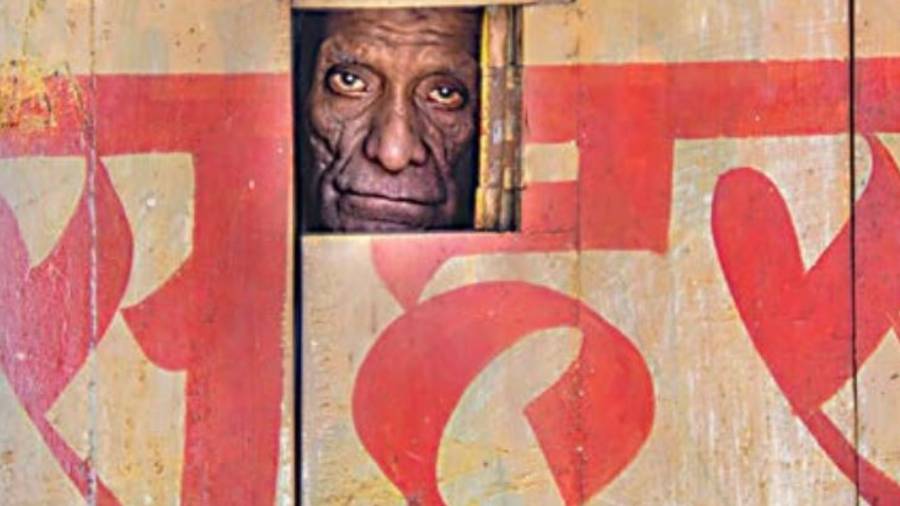

When I moved into the neighbourhood in 1996, the shrine was made up of a few bricks and a framed photograph of a deity. Bang opposite was a water tank, frequented by the residents of the slum next door and taxi drivers who found it an ideal place to wash their vehicles.

The slum was not very popular in the neighbourhood although my family found it convenient. One, our rent in the leafy locality was affordable because of the proximity of the slum that kept the amount on a leash. Two, it was easy to hail a cab at any time of the day as many cabbies lived in the slum — a blessing when it came to sending our child off to school.

Slowly, the slum disappeared and a bungalow and an apartment block came up in its place. Everybody was happy — me too. We had a car by then, who needs cabbies now?

But the tank, tied to the tide in the Ganga, was a “nuisance”. The slum had moved but not the cabbies who kept returning to the source of water to scrub their cars. The ungainly yellow cabs, dented and damaged, did not go well with the Lamborghini and the BMW that were beginning to strut on our small lane.

One night, returning from the newspaper office, I saw that the tank had caved “itself” in, burying itself forever. The bright red bricks, evidently smashed with some heavy object, reminded me of weeping wounds. Now, there is no trace that such a tank ever existed.

Everybody was happier — me too. Warts and other eyesores removed, surely our net worth would go up in the real estate market.

I didn’t notice it initially. In a coincidence or otherwise, the fall of the tank was marked by the rise of the temple. Our little shrine was going places: marble replaced the bricks and an iron grille was put in place. There were valuables inside: a digital clock and gleaming utensils for the rituals.

As a child, I had been taught to do pranam to anyone or anything that is honoured by others. “Namaste” means “the divine in you is saluting the divine in those facing you”, I had been told. So, I do pranam at our neighbourhood temple, too, when I get off the night drop.

It is the same salutation that the milkman is offering the deity at the pre-dawn hour. When I was in Delhi in the early 1990s, we used to greet Hindus who looked religious with a “pranam” and others with a “namaste”. Now, I hear “Jai Shri Ram” more frequently. I am fine with that. Ours is not a godless nation.

Back to the night. I remember I had not heard the 3.55am “Jai Shri Ram” for quite some time. In fact, I could not remember having heard it at the same hour since the 2021 Assembly elections. Or, perhaps I did but it did not register. And perhaps it was registering now because of what had happened in Howrah a few hours earlier.

Like soldiers, cynical journalists also “wargame” — an indulgence in the great unknown: what if?

Taking off from that “Jai Shri Ram” that pedalled past me, I started wondering: what if a religious procession landed at my home, brandishing swords, taunting and baiting my family? I have Christians in my family. Cottage prayers that involve singing, which can be heard in the neighbourhood, used to be held at my home.

Then I did something I had never done before: I started drawing up in my mind a list of families from any of the minority communities in my neighbourhood. I could not readily recall any such family, which is not a bad thing. It showed how irrelevant such information is and how secular my neighbourhood is. Our faith does not matter.

But “what if”? The war game of the cynic.

I recalled Ali-da, a tailor who pedalled his stitching machine at the home of a Gujarati Hindu family down the road. The family had an upholstery business. In the winters, I have seen Ali-da sleeping on our premises. He was fond of our daughter. Then, Ali-da died in an accident. After that, I had not come across any resident from any minority community in the locality, other than employees of a nearby salon. Perhaps, there are others. But I don’t know anyone. My problem. Not anyone else’s.

It was turning out to be a night of lists.

I asked myself if I had the local police station number: No.

The local councillor’s number? Nope.

The number of any public figure nearby who can help me? Nope.

These were the first ports of call when we were in distress in Kerala where I grew up.

The very absence of these numbers on my Calcutta contact list is perhaps the greatest tribute I have unwittingly paid to Bengal. The utter insignificance of these numbers for an outsider like me shows my deep trust and faith in Bengal to protect my family.

Dawn is breaking. I catch sight of the Tricolour at our neighbour’s. It is neither flying high nor fluttering in the manner in which it comforts us when we are in trouble.

The flag is twisted around its pole. A creeper has found the pole a reliable prop.

The flag has a history: it was hoisted in response to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s appeal last year to the citizens to strengthen the “Har Ghar Tiranga” movement. The flag was supposed to have been hoisted or displayed at homes between August 13 and 14, 2022, and taken down with decorum and respect on the evening of Independence Day.

Specific norms had been issued on how to fold the flag, after which it had to be carried in palms and then stored. If the flag was damaged or soiled, there were other norms to fulfil.

My good neighbour, who has given me no trouble at all, must be unaware of the fine print. The Prime Minister’s call was given wide publicity but not the attendant drill to preserve the dignity of the Tricolour.

Considering that this flag has outlived the government order by over 235 days, it has acquitted itself remarkably well. If it is extricated from the pole and the norms are fulfilled, I think it can be preserved and used this year, too.

March 31-April 7

Reports of violence from more places. Union home minister Amit Shah wants rioters hung upside down.

Bad timing. The same day, the news agency PTI reports that several people accused of rioting and rape in Gujarat in 2002 had been acquitted for want of evidence. If the investigating and prosecuting agencies don’t work hard enough to serve up rioters on a platter, how will Shah hang ‘em upside down? “Hang ‘Em High” used to be the stuff of Spaghetti Westerns. Nice to know what the Chanakyas of our time watch on Netflix.

The Union home ministry issues an advisory to all states on the eve of Hanuman Jayanti to ensure law and order. Uttishthata, jagrata!

The high court asks the Bengal government to requisition central forces on April 6, Hanuman Jayanti.

The next day’s headlines reassure the citizenry: Hanuman Jayanti was peaceful.

April 5-6

At 6.54am on April 5, a close family friend — an entrepreneur — sends by WhatsApp an article titled “Muslim Personal Law is an embarrassment” and a message: “I follow this columnist.”

I am touched by his concern for the welfare of Muslims. I know for a fact that he is behind an initiative to help educate Muslims.

I get the message in his message. I wonder why he has not mentioned anything about the violence that unfolded in our beloved state and elsewhere in the country in the name of religious festivals.

Or about Rabia Khatun and her family who saved five Hindus in Howrah.

Or, later in the day or the next day, about the glee of the Bajrang Dal leader who is salivating at the prospect of the clashes offering a fertile ground for his outfit in Rishra.

Perhaps my friend, a frequent flier overseas, is not in the country.

I recall with sorrow what academic Gautam Menon had tweeted after the first day of violence: “We ignore these signs at our own peril. The relentless stoking of communal hatred has consequences that may well be irreversible. Perhaps they already are.”

It is Lent. A time to forgive. A time to heal. Silence holds a deep significance — in gratitude for the moment in solitude in the desert.

So, I reply to my friend: “Excellent.”

My friend replies: “I was sure it would resonate with you.”

He sends another link: “The one below is an even stronger piece.”

It is headlined: “Reform Muslim Personal Law now. It’s communal, sectarian and anti-Islam.”

During the Emergency, one of my former editors had printed in another newspaper verses from the Gitanjali when the censor asked him to remove a news report.

So, I send my friend a clip showing Jimmy Fallon overdosing on John Wick: Chapter 4 with Keanu Reeves seated next to him. I don’t know why I chose that clip. Perhaps, it is because Keanu’s lead character apparently utters only 380 words in the nearly three-hour film.

My friend is yet to reply.

My friend is a model citizen, made in old India and kitted out for New India. A Hindu, he has had an inter-faith marriage, which takes care of his secular credentials. He swears by the Constitution — that is his holy book.

My friend is fair: He grieves for Ankit Sharma, the IB official who was brutally murdered during the Delhi riots, in the same manner in which he mourns Mohammed Akhlaque, who was lynched over suspicion that he had stored beef at his home.

My friend trusts the government: He feels the insecurities associated with the CAA-linked citizenship matrix are hyperbole.

My friend is not jingoistic: He loves Pakistan (the people there). He likes beef too, but prefers to have it abroad since the Indian quality is not up to the mark.

My friend is well-meaning: All he wants is to ensure the welfare of his fellow citizens, the Muslims.

April 8

A journalist sends me a Princeton University link to an interview with Prof. Ashoka Mody, the author of India Broken: A People Betrayed, Independence to Today. The interview was published in March but it has reached me now through the winding Silk Road on WhatsApp.

Explaining the basic premise of his book, Prof. Mody says: “The elite are happy in their gated first-world communities. They shrug their shoulders and say, ‘What exactly is the problem?’”

Yes, what exactly is the problem?

Soon, there will be another religious festival. Then another.

Uttishthata, jagrata!