Two independent members of the National Statistical Commission have resigned because of a reported disagreement with the Narendra Modi government over its failure to publish a report on employment that had been prepared last month.

The two members are P.C. Mohanan and J.V. Meenakshi. Mohanan was also the commission’s acting chairperson.

The commission is now left with only two members: chief statistician Pravin Srivastava and Niti Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant.

“The two members have resigned from the National Statistical Commission and tendered their resignation on January 28,” an official said.

Mohanan told a news website he had decided to quit because he felt he wasn’t making “any effective contribution”. “We are not discharging the duties of the commission,” he added.

He said one of the reasons he had decided to quit was the government’s failure to release the jobs report. “We have approved the report, but they have not released it, I don’t know why,” he told Scroll, the website.

The tenure of Mohanan and Meenakshi was to end in June 2020. They had joined as members of the NSC in June 2017.

The Modi government has been extremely sensitive about criticism that the economy may be growing at over 7 per cent but it hasn’t led to the creation of jobs.

Over the past year, the government has refused to release reports by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) and its labour bureau. Instead, it has tried to extrapolate statistics based on payroll data sourced from the Employees Provident Fund Organisation, Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority (PFRDA) and the Employees State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) to show that there has been a steady increase in jobs in the past four years.

Four days ago, the government put out statistics to show that more than 18 million jobs had been generated in the country's formal sector during a 15-month period starting September 2017 and ending November 2018.

But several studies have contested the government’s claims.

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), India’s unemployment rate was recorded at 3.5 per cent in 2018 and it could grow in 2019. The data suggested that there will be 18.9 million or jobless people in India in 2019.

A study the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) said that India’s unemployment rate had shot up to 7.4 per cent in December 2018.

“This is the highest unemployment rate we’ve seen in 15 months,” said Mahesh Vyas of CMIE. “The rate has increased sharply from the 6.6 per cent clocked in November. The climb to 7.4 per cent also indicates that the small fall in the unemployment rate seen in November was possibly an aberration in a trend that indicates a steady increase in the unemployment rate.”

“The count of unemployed has been increasing steadily. Over the year ended December 2018, it increased by a substantial 11 million. Correspondingly, the count of the employed is declining. In December 2018, an estimated 397 million were employed. This is nearly 11 million less than the employment estimate for December 2017,” Vyas wrote in a report.

This isn’t the first time that the government has run into controversy over reports prepared by the National Statistical Commission.

In November last year, the Niti Aayog had come under fire for announcing the revised GDP data of the UPA years.

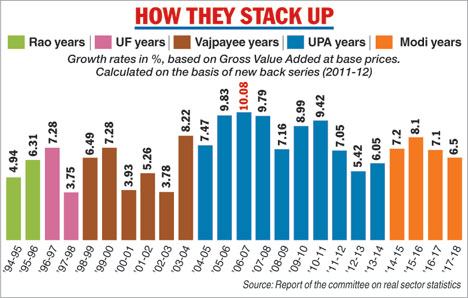

Niti Aayog vice-chairman Rajiv Kumar and Chief Statistician Srivastava had announced the back-series data by the government in an attempt to show that economic growth during the NDA regime was far higher than that during the 10-year UPA tenure.

In the process, the government was trying to head off the embarrassment sparked last August when the National Statistical Commission had come out with figures that claimed that the earlier Congress-led government under Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had achieved a double-digit growth rate of 10.8 per cent in 2010-11.

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) said the average growth rate during the UPA regime tenure of 2005-14 was 6.7 per cent compared with the NDA growth of 7.3 per cent in 2015-18.

Back in August, an NSC sub-committee headed by Sudipto Mundle, emeritus professor of the National Institute of Public Policy, had estimated that the average growth during the decade-long UPA tenure was 8 per cent compared with 7.3 per cent during the NDA regime.

The Mundle committee had triggered a controversy -– and created bragging rights for the UPA — after it calculated the new growth rates for the years 1994-95 to 2013-14 on the base year of 2011-12, thereby creating a back series enabling like-to-like comparison.

Recalibrating data of past years using 2011-12 as the base year instead of 2004-05, the Central Statistics Office (CSO) estimated that India’s GDP grew by 8.1 per cent in 2006-07 and not 9.7 per cent as estimated by the Mundle report.

Similarly, the Mundle report’s estimate of a growth rate of 9.6 per cent in 2005-06 and 10.2 per cent in 2007-08 were lowered to 7.9 per cent and 7.7 per cent, respectively.