Sreerupa, a 15-year-girl I have been seeing for more than two years, said she was extremely happy with her online classes. She has been struggling with anxiety disorder and never enjoyed school because of bullying. I was ‘seeing’ her after a gap of three months for a review, using an app for telemedicine. I was quite pleased with her progress, but her next statement deflated my optimism. She said she hopes the pandemic lasts and that she never has to go back to school ever again. Then she listed the advantages of online classes. She did not have to meet her bullies and did not feel the pressure to respond in a class. She said she felt comfortable being silent and was able to communicate with her teachers about her doubts and clarifications through email or messages.

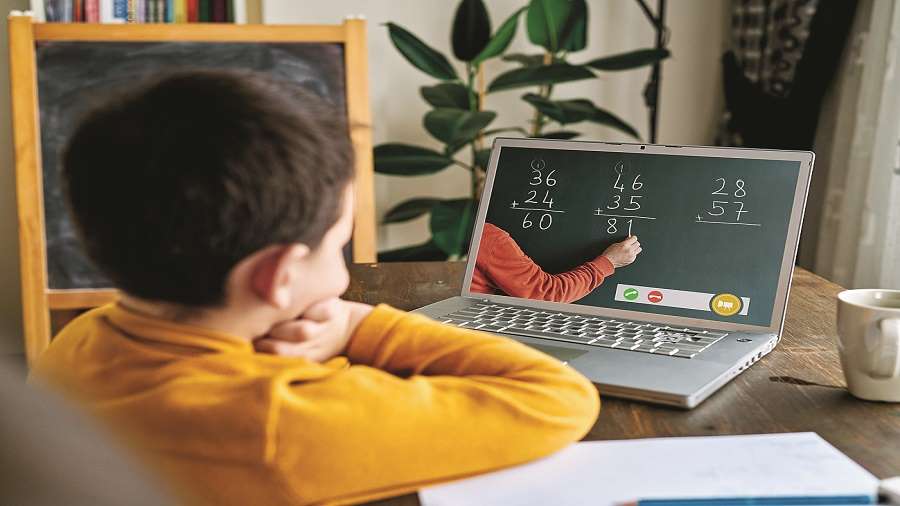

We have been inundated with news items on online classes and how the world has to adapt in the post-pandemic world. ‘Blended learning’ and ‘new normal’ are two phrases that have been added to our lexicon. But is this ‘normal’? Will it ever be ‘normal’? Blended learning, apparently, is the future. To be honest, I was quite taken with the idea initially. I was biased. I had personally started using telemedicine and felt gratified that I was able to reach out to many who otherwise would not have had access to services because of the lockdown. A panel discussion on national television channel featuring CEOs of educational technology platforms and international experts laid out the bright future of online learning. They were exuberant about the prospects and potential it offered.

Slowly my initial optimism started faltering. Harrowing coverage of migrants in transition with young children in tow punctured the belief that online education would mean more access to education for all. A news item of a young girl’s suicide because she missed her online classes as her father could not repair his phone, drove home the point that our privilege truly blinds us to the reality of the lives of others. Comfortably cocooned in my privilege, my rosy optimism about how the technological leap necessitated by the pandemic, will lead to more access to health and education for many more in our country, was horribly skewed.

During my interactions with young people and their parents, who braved and came to a hospital’s outpatient department, I learnt more about the reality of these online classes, the quality and content was hugely variable. For parents of pre-teens, it was very stressful. A couple of parents, whose children were three or four years old, told me that their children too were having online classes!

I see a significant number of children with disabilities. For them, online classes were an extremely poor substitute even when parents were sitting with them. Most parents were having to do more at home, so most of them complained of fatigue and tiredness as a result of having to supervise their wards during online classes. Those teenagers whose parents had been concerned about screen time, now had a legitimate excuse to bury their faces on the screen. Their parents had no way of knowing what they were doing with increased access to the Internet and devices. Online education was a convenient excuse to indulge more time playing games on tabs and phones.

A sense of feeling helpless

Schools are much more than a place where ‘classes’ are held. It is a social space, a microcosm of our communities, where a lot is learnt apart from what is in the textbooks. Online education can never replace the life-skills learning that happens in schools.

The senior teachers I spoke with were unhappy. Many said that taking online classes required a different skill set compared to what it takes to be a good teacher in a conventional classroom. They complained about parental interference during classes, that is, ‘helicopter’ parents and students attention flagging in a virtual classroom. “I am not cut out for this” was the opinion of a very senior teacher whom I have known for many years.

My own experience of telemedicine also reinforced what I was picking up in my conversations. It is not the same as ‘real’ consultations by any stretch of imagination. Convenient maybe, but not the same. Neither is seeing patients with masks, face shields and gloves, who are sitting at least six feet apart in our outpatient departments. Facial expressions, which are so important in conveying emotions in our profession, is ‘masked’. I cannot get my head round to the fact that this is the ‘new normal’ now.

Then there is the sense of feeling helpless and not being able to help those who have been under our care for years. There are elderly people who are not tech savvy and comfortable with gadgets and neither can they come to the hospital to seek treatment. You get calls from them and their relatives, who live away. How do you respond?

You hear stories of relatives who were not able to say goodbye to their loved ones after they have died, of persons dying on the streets after not getting admission in hospitals, of doctors making gut-wrenching choices on whom to allocate a ventilator in preference of another sick person. You sit across a 13-year-old boy weeping, who is worried that his father who is a police officer posted to screen migrant labourers coming home, might acquire Covid-19 and may die because he feels his father cares more about others than about his health. If this is what a new normal is going to be, I realise that I need more courage and resilience to live with it.

I really long to go back to a somewhat more normal than this ‘new normal’. I have questioned myself. Am I clinging on to the concept of what is ‘normal’ because I have been so comfortable in it like the rest of us?

Probably not. I cannot really fathom how this prevailing situation could be ‘new normal’ for crores of people who have lost their jobs, and for all those children who were dependent on mid-day meals in their schools and for whom school was a sanctuary. The ‘new normal’ will probably be easier for the very few, but not for most.

After I wrote this piece, I did not send it. I realised it was more about my angst and despair. However, I feel many of us are feeling stifled with the ‘new normal’ and I would feel better if I shared it with all of you. I am aware that there are no immediate and easy solutions. It will be a long haul and we will adapt and survive. This too shall pass, is what I often tell others who come to me. I am holding on to that myself.

Dr Jai Ranjan Ram is a senior consultant psychiatrist and co-founder of Mental Health Foundation (www.mhfkolkata.com). He is also a wildlife enthusiast