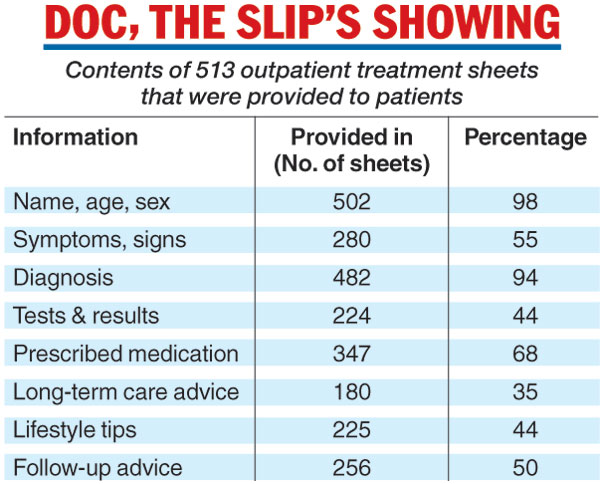

While 482 (94 per cent) of the 513 outpatient documents examined contained the diagnosis, only 347 (68 per cent) listed the medications prescribed. Some 224 (44 per cent) contained information about the tests carried out and their results, while 225 (44 per cent) contained lifestyle recommendations dealing with diet, tobacco or exercise.

The researchers say their findings, published this week in the journal PLOSOne, suggest that patients with non-communicable diseases may receive “substandard” continuity of care because of the poor information-transfer practices.

“Adjusting the dosage of medications is critical in chronic conditions, whether high blood pressure, diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” said Jeemon Panniyammakal from the Sri Chitra Tirunal Institute of Medical Sciences and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram. “And (to be able to) adjust the dose, a doctor needs to know exactly what medications have been prescribed and at what doses. Without reliable information, the next doctor the patient visits may initiate the treatment again, which may provide poor-quality care to the patient. This may at times harm the patient.”

The study has also identified what the researchers say are barriers to the continuity of care.

Large patient loads at government clinics cut the time doctors have to provide verbal or written information to the patients. Besides, many doctors have never received structured training in clinical handover.

Most of the treatment documents screened during the study were jottings on sheets of paper that lacked a well-defined structure.

The researchers say that networks of electronic medical records could provide seamless information transfer and improve the continuity of care, and that standardised booklets for patients might help until such networks have been put in place.

Only a fourth of patients with chronic diseases who attend government clinics in India receive all the key information they need for future follow-up care by other doctors, a study has suggested.

Only 24 per cent of the outpatient clinic documents the study screened mentioned all four pieces of key information: the diagnosis, prescribed medication, long-term care instructions and follow-up information.

The study found that 32 per cent -– nearly one in three -– did not mention the medications prescribed.

Public health researchers participating in the study, the first systematic assessment of health-care communication in Indian government clinics, assessed over 500 treatment sheets given to patients in five health-care facilities in Kerala and Himachal Pradesh.

“The transfer of patients’ information from one doctor or hospital to the next is critical, particularly so in India where many patients may not always be able to convey information,” said Shifalika Goenka of the Public Health Foundation of India, New Delhi.

In medical circles, this information transfer is called “clinical handover” and is particularly crucial to the care of chronic, non-communicable disorders such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, longstanding respiratory disorders and kidney disease.

The study has also found that the health-care information provided to the patients is often poorly recorded on unstructured sheets of paper. Just over half the patients recalled receiving verbal information on both medication and follow-up care.

The Telegraph