Even as vaccines are hailed as our best hope against the coronavirus, dozens of scientific groups are working on an alternate defence: monoclonal antibodies. These therapies shot to prominence after US President Donald Trump got an infusion of an antibody cocktail made by Regeneron and credited it for his apparent recovery, even calling it a “cure”.

Monoclonal antibodies are distilled from the blood of patients who have recovered from the virus. Ideally, antibodies infused early in the course of infection — or even before exposure, as a preventive — may provide swift immunity.

An enthusiastic Trump has promised to distribute these experimental drugs free to anyone who needs them. But they are difficult and expensive to produce. At the moment, Regeneron has enough to treat only 50,000 patients; the supply is unlikely to exceed a few million doses in the foreseeable future.

Dozens of companies and academic groups are racing to develop antibody therapies. Regeneron and Eli Lilly have requested emergency-use authorisations for their products from the US Food and Drug Administration. These drug companies have the long experience and deep pockets needed to win the race for a powerful antibody treatment. But some scientists are betting on a dark horse: Prometheus, a ragtag group of scientists who are months behind — and yet may ultimately deliver the most powerful antibody.

Prometheus is a collaboration between academic labs, the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, and a New Hampshire-based antibody company called Adimab.

The group’s antibody is not expected to be in human trials until late December, but it may be worth the wait. Unlike the antibodies made by Regeneron and Eli Lilly, which fade in the body within weeks, Prometheus’ antibody aims to be effective for up to six months.

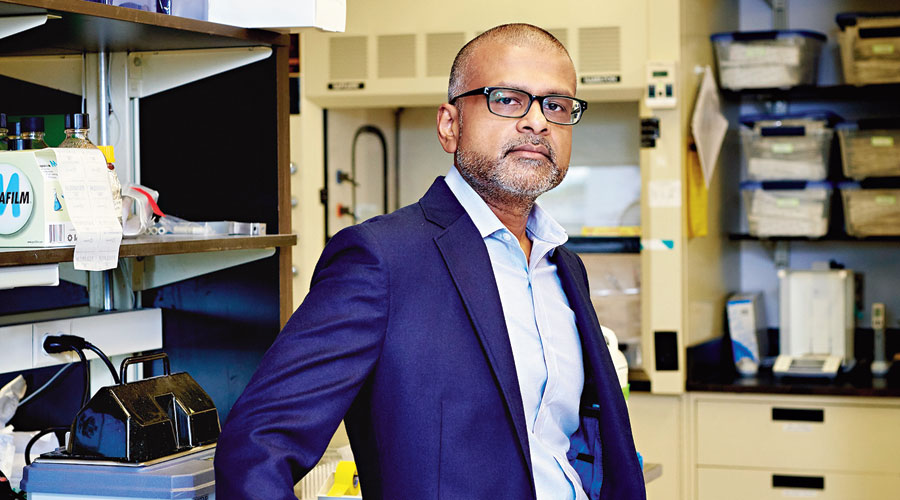

“A single dose goes a long way, meaning we can treat more people,” said Kartik Chandran, a virologist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, US, and the group’s leader.

In mice and laboratory tests, Prometheus’ antibody protects against not just the coronavirus but also the Sars virus and similar bat viruses — suggesting that the treatment may protect against any coronaviruses emerging in the future.

Virologist Kartik Chandran New York Times News Service

Outgunned at first

Antibodies are as variable as the people who produce them. Some antibodies are weaker, some target a different part of the virus and some are powerful protectors, while a small number may even turn against the body, as they do in autoimmune diseases.

Monoclonal antibodies are artificially synthesised copies of the most effective antibodies produced naturally by patients. In late February, AbCellera fished out an apparent winner from among 550 antibodies drawn from the blood of an infected patient. Barely three months later, partner Eli Lilly began the first trial of a synthesised version in patients.

Regeneron’s drug is a cocktail of two antibodies: one was discovered in a patient in Singapore, while the other was made using a synthetic viral snippet in mice.

Days before Trump received his infusion, Regeneron announced that this cocktail seemed particularly helpful for people who did not produce enough antibodies of their own against the coronavirus.

Without the resources or reach of these bigger companies, Prometheus has lagged behind.

With a $22 million federal grant, the group had been developing therapies for deadly viruses like the one causing Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever and various hantaviruses. But in the earliest days of the pandemic, the group was not able to take on the coronavirus.

“We had all of the technology, all the tools ready to go,” Chandran said. “The only thing we didn’t have was a patient sample.”

Most of those samples had been handed to large pharmaceutical companies by the federal government. So the Prometheus researchers took an unusual tack, instead relying on blood from a survivor of the 2003 Sars outbreak. (The coronavirus is a close cousin.)

These scientists had experience. One, Jason McLellan of the University of Texas at Austin, US, was an expert in coronaviruses; another, John Dye of the army’s infectious diseases institute, had done pioneering work on Ebola antibodies.

In March, McLellan was the first to publish the structure of the new coronavirus in Science. He supplied Adimab, Prometheus’ commercial arm, with the pathogen’s “spike protein”, a protrusion on its surface that latches on to human cells.

Using the protein as a lure, Adimab snared 200 antibodies from the patient sample. Chandran screened those antibodies against a proxy for the coronavirus, and Dye against the live virus in a high-safety laboratory.

Together, they refined the list to seven antibodies that recognised both Sars and the new coronavirus. Scientists at Adimab then enhanced the neutralising power of one antibody by about 100-fold, yet retaining its effectiveness against all Sars family coronaviruses.

Too complicated to make

Monoclonal antibodies can rapidly prevent the virus from taking hold in the body — say, in residents of a nursing home with one confirmed case of infection. Vaccines, which require weeks to unspool an immune response, are useless in such a scenario. But limited production capacity is likely to keep monoclonal antibodies out of reach for most people.

The antibodies are also expensive to produce. Some cost up to $2,00,000 — even the cheapest cost about $15,000 — per year of treatment, making them unattainable for all but the richest of countries.

“I don’t see monoclonal antibodies being in large-scale use in the public,” said John Kokai-Kun, the director of external scientific collaboration at US Pharmacopeia, an organisation that monitors manufacturing quality. “They’re just too complicated to make and too expensive to really be effective.”

Like vaccines, the antibodies have to be injected, and the amounts, which are calibrated to a person’s weight, can be significant. (Trump received 8 grams — vaccine doses tend to be in micrograms or even nanograms.) The protection wanes after just a few weeks.

“That puts a strain on your manufacturing infrastructure already to make the kinds of doses that we think are going to be required worldwide,” said Andrew Adams, vice-president at Eli Lilly. “We have to start thinking about the populations that we should prioritise.”

New York Times News Service