Not long ago, a panel of influential medical experts recommended for the first time that doctors screen all adult patients under 65 for symptoms of anxiety.

The new guidelines were issued by the US Preventive Services Task Force after a draft was released in September. Earlier in 2022, the experts had made similar recommendations for children aged between eight and 18.

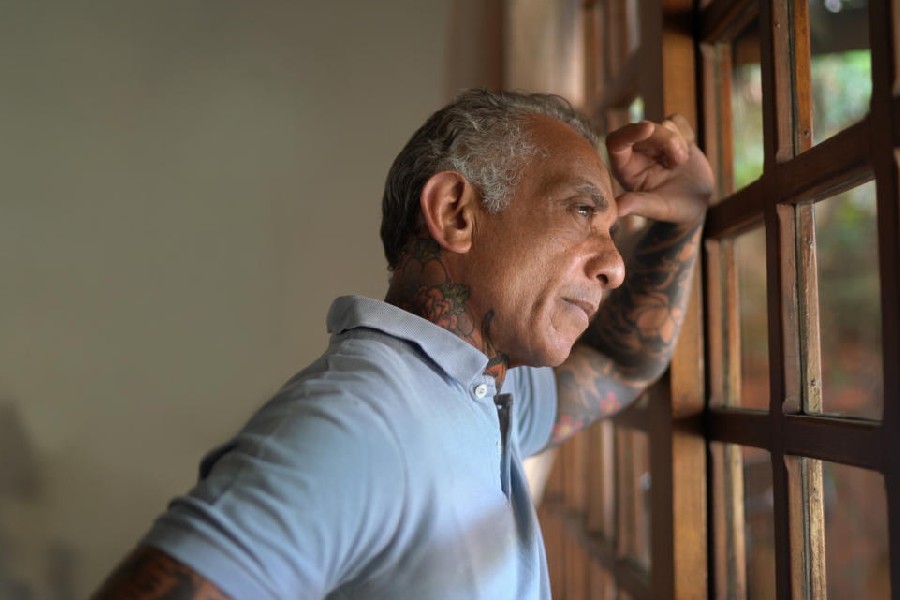

Millions of Americans struggle with anxiety. About one in five adults in the US has an anxiety disorder, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Having some anxiety isn’t necessarily a problem. Experts say an internal alarm system benefits us in various ways, helping improve our performance or recognition of danger and encouraging us to be more conscientious. In addition, it’s common to feel more anxious when faced with stressful events such as the death of a loved one, starting a job or moving to a new city.

At times, however, anxiety can become more pervasive and overwhelming.

How do you distinguish the normal protective anxiety from the more problematic excess anxiety? And what do you do if you’re 65 or older and have been feeling anxious?

Dr Petros Levounis, the president of the AmericanPsychiatric Association, answered these questions and more via email. Here are the edited excerpts.

How do you know if your anxiety level is in needof evaluation?

Anxiety can cause people to try to avoid situations that triggeror worsen their symptoms. Some signs to look out for include a sense of dread or worry that won’t go away or trouble sleeping or eating.

Other symptoms may include restlessness, a sense of fear or doom, increased heart rate, sweating, trembling and trouble concentrating.

If you feel as if the worry is getting too much and it starts affecting your work, your relationships or other parts of your life — or you feel depressed — it might be time to speak with a primary care provider or a mental health professional. The anxiety may get worse if you don’t ask for help.

What are “normal” levels of anxiety? How much can be considered is too much?

We all feel anxious from time to time. If you have a big test, family worries or concerns about paying your bills, you can start feeling nervous. Your heart may beat faster, you’ll notice you are sweating more, you feel on edge. Sometimes that feeling disappears as quickly as it arrives. But if that worry and fear are there constantly, you need help.

What is the treatment for anxiety like?

The first step is to see your doctor to make sure that there is no physical problem causing your symptoms. If an anxiety disorder is diagnosed, a mental health professional can work with you on finding the best treatment. Most people respond well to psychotherapy, or “talk therapy,” and medications. A combination of both has been found to be the most effective.

Cognitive behavioural therapy, a type of talk therapy, can help a person learn a different way of thinking, reacting and behaving to help feel less anxious. Medications will not cure anxiety disorders but can provide significant relief from symptoms. The most commonly used are anti-anxiety medications and antidepressants.

What about older adults? What should they do?

Just ask! You may know that anxiety often comes with an overwhelming feeling of nervousness, fear and worry for long periods of time. But anxiety can also have physical symptoms like shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain or gastrointestinal issues. Older adults may think this is just a sign of aging. But it’s important to share all of your symptoms — including your emotional concerns — with your doctor.

Does a positive screening mean that you will need treatment?

Clinicians should follow up positive screens with questions, such as the duration of symptoms, degree of distress and impairment, and treatment history.

Screening for any mental disorder without appropriate follow-up is potentially harmful. Steps like screening and brief interventions for those with depression and anxiety can go a long way toward increasing early detection of mental health disorders as well as the prevention of life lost to suicide.

New York Times News Service