Friday, 10 January 2025

Friday, 10 January 2025

Friday, 10 January 2025

Friday, 10 January 2025

Could the thick clouds of pollution hanging over Pakistan and northern India finally bring these two foes together in a way that nothing else has in the last 77 years?

Lahore has just snatched the crown from Delhi to become the world’s most heavily polluted city. Last week, Lahore’s Air Quality Index (AQI) hit a stratospheric 394, leaving Delhi huffing and puffing but far behind at levels between 230 and 305 — though such levels are still perilous.

Delhi is now such a sprawling metropolis that AQI varies significantly across different areas of the city. For reference, air quality is considered safe up to 50 and dangerous beyond 150.

Pakistan’s Punjab chief minister Maryam Nawaz Sharif has been the first to openly suggest the need for creative "climate diplomacy" with its giant neighbour, amid industrial emissions, heavy traffic, construction dust and relentless crop burning that have turned the air into a health hazard.

"We should talk to them, this is called climate diplomacy. We should do it with India," Sharif said as pollution began climbing steadily again in both countries — even before crop residue burning got into full swing.

The crop burning that blankets the Indo-Gangetic plains with smog and PM2.5 particles, which penetrate deep into the lungs, peaks in November.

When winter rolls around, things get even worse due to a mix of lower wind speeds and temperature inversion — a phenomenon where a blanket of cold air traps pollution close to the ground, creating respiratory troubles and worsening asthma, heart risks, and other health problems. Doctors say the pollution crisis is pushing urban India to the brink.

Experts say India and Pakistan do have a choice: they could seek to alleviate the problems by working together.

“While climate diplomacy between India and Pakistan has been proposed, real collaboration on this issue remains sparse,” observed an editorial in leading Pakistan daily Dawn.

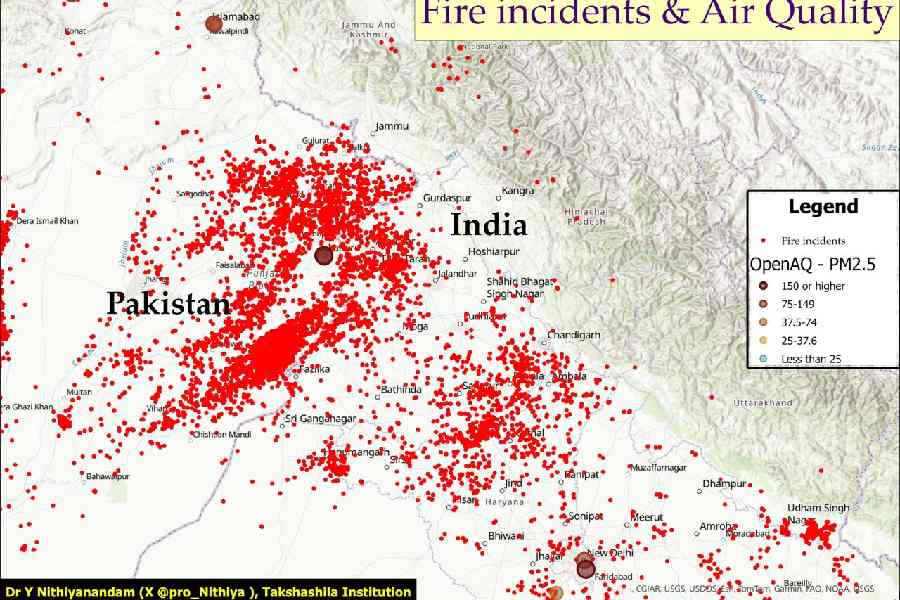

Satellite maps reveal that Pakistan now has an even greater number of “fire incidents” than India, crucially concentrated in much smaller areas, so a single incident can quickly affect the economy.

The direction of the wind largely determines which country gets the worst of the smoke from these fires at any given time. Additionally, the flat plains spanning both sides of the border mean no natural barriers can prevent polluted air from flowing in the direction of the wind.

Earlier this month, the light winds were mostly blowing towards Pakistan, so that country got the worst of the choking pollution.

“The wind pattern was transporting smoke from India to Pakistan, reducing visible pollution in Indian monitoring stations,” said said Y. Nithiyanandam, professor, Takshashila Institution.

“However, this balance tilts when the wind reverses, especially around events like Diwali,” Nithiyanandam noted.

In the second half of October, the wind shifted towards India, compounding pollution with the pre-Diwali season, when fireworks typically spike pollution levels.

“Fire incidents outside and within India are higher this week, and the wind is blowing smoke into the cities," said Nithiyanandam. "Air pollution is not just India's problem — it’s a transboundary crisis. The stubble burning isn’t just happening in Indian states but beyond our borders."

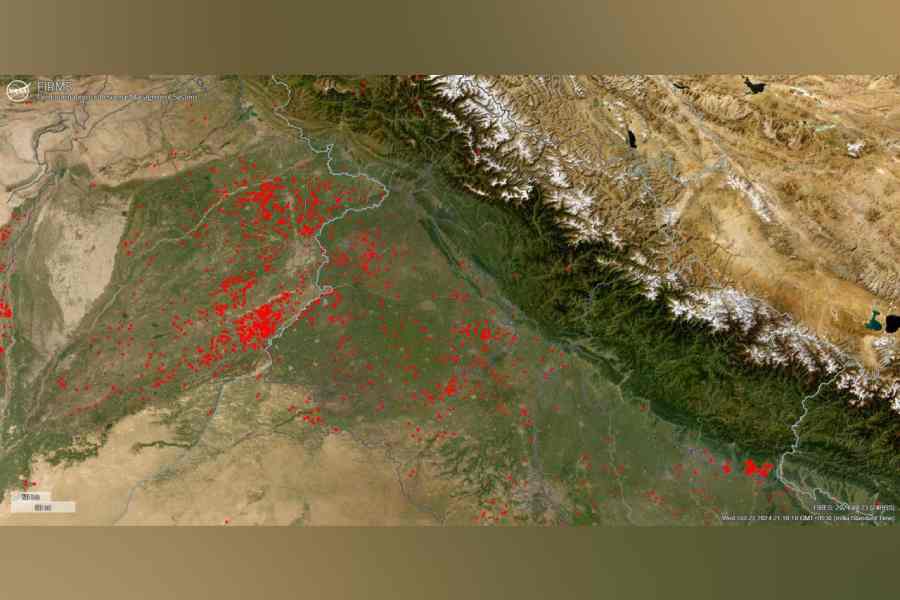

Satellite images, which capture both day and night, show many fires are set at night to avoid detection.

"Police are obviously more vigilant during the day," said Nithiyanandam. "Nighttime enforcement remains limited, enabling farmers to circumvent penalties. But the satellite images capture both night and day, so people can't escape from it."

Both countries are taking steps to curb crop-burning fires. India appears to be adopting a stricter approach with fines and arrests, though it remains cautious to avoid alienating the farming community.

Using satellite images to monitor fire activity in real time, “by clicking on any fire location, we can see how intense the fire is, showing whether it's small or large. This information is essential for understanding how pollution spreads,” said Nithiyanandam.

Incorporating this technology into joint monitoring efforts would help prioritise the most serious fire incidents for quick action.

Additionally, the flat plains spanning both sides of the border mean no natural barriers can prevent polluted air from flowing in the direction of the wind.

Alongside satellite monitoring, the Takshashila Institution has released a document titled Environmental Cooperation: An Imperative for Subcontinental Thinking. The document stresses that, "While India and Pakistan may have their differences, climate change poses a more potent threat to them than they do to each other."

It adds: "These issues cannot be resolved by any one nation-state alone; political borders don’t apply to climate problems, and solutions can’t be effective if they come from only one country."

Takshashila’s report also highlights that similar weather conditions have a sharp impact on both sides of the border at other times of the year.

It points out: “Over the past three decades, the entire region has experienced a notable rise in heat levels, driven by urban heat islands and the broader impacts of heat waves.”

This year, India experienced record-breaking heat. Churu in Rajasthan, for instance, saw a peak of 50.5°C while Pakistan has also experienced record-shattering heat waves.

Addressing this shared challenge “requires joint efforts to mitigate local and regional heat impacts,” the document says.

The foundation advocates for collaborative research in early warning systems, the exchange of best practices, and cooperation in space-based technologies and research.

This, it says, “can play a vital role in reducing the adverse effects of urban heat.”

While climate cooperation could help bring down pollution levels, it’s not the only solution. In Delhi, for instance, vehicle emissions and cooking fires are major contributors to pollution levels year-round, although crop fires add significantly to the problem during winter months.

Nithiyanandam said we should focus on cooperating across borders to effectively manage air quality, stopping polluted air from moving freely between countries. By coordinating when we plant crops and managing water resources better, we can reduce the number of fires on both sides.

Using satellite images to monitor fire activity in real time, “by clicking on any fire location, we can see how intense the fire is, showing whether it's small or large. This information is essential for understanding how pollution spreads.”

Incorporating this technology into joint monitoring efforts would help prioritise the most serious fire incidents for quick action.

Ultimately, a healthier future might be possible if both nations prioritised clean energy, enforced pollution regulations, and worked in tandem to beat the ever-thicker clouds of smog. The benefits from reducing pollution would be immense.

“We can either breathe easier by working together – enforcing anti-pollution measures, adopting modern farming methods, and prioritising clean energy – or we can choke separately,” said one Indian pollution expert.