There’s nothing unusual about Sundays. Pork Vindaloo simmers on the stove, moka pot slowly bubbles on another burner, the wife lays out the table, our daughter prepares lemonade while I lord over the stiffness of the meat. Of course, the cat speaketh now and then from her cupboardhigh perch, with her subtitles matching the mumbling dialogues on the television. We manage, thanks to subtitles. We, in fact, have learned to slow down our speeches to give a feel of subtitles as we speak. We consider ourselves the Subtitle Family.

There’s a rule in the family — before renting (or occasionally purchasing) films via Google Play Movies or Apple TV+, subtitles are a must. No subtitles and that Oscarwinning movie will get cancelled from our list.

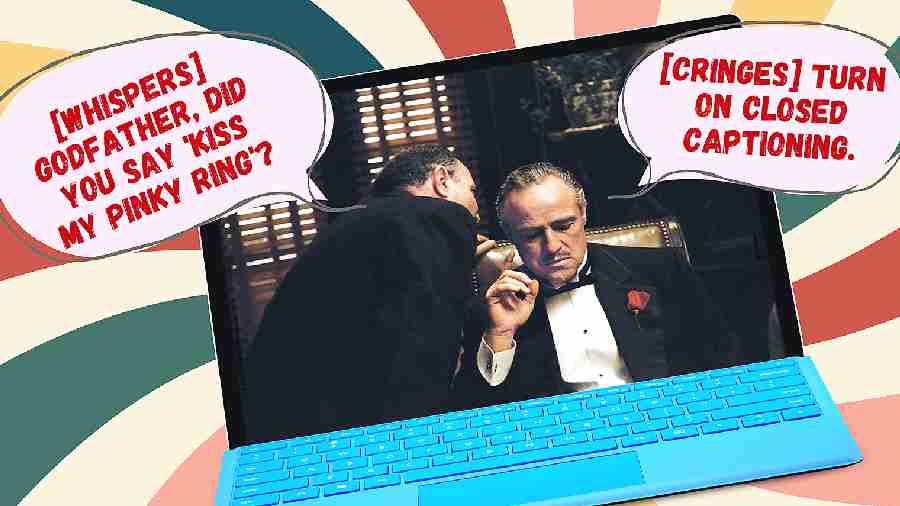

Subtitle “families” are everywhere, spreading quickly in the last few years. Come again, what was that Bane and Batman (Tom Hardy and Christian Bale)? Huh, Jeff Bridges? Enunciate, enunciate? But wait, is it always the fault of mumbling actors, led by Marlon Brando’s Vito Corleone? The rise of subtitles can be attributed to many things.

Last year, Netflix said that 40 per cent of its global users have subtitles on all the time, while 80 per cent switch them on at least once a month. Many prefer closed captions but if push comes to shove, open captions work.

Subtitles are nothing new. When DVDs and Blue-rays were popular, one could press a button on the remote to change the subtitle language. The subtitle file was “authored” or encoded onto the disc and it was separate from the movie’s image, so it can be superimposed in sync with the movie. Closed subtitles were unique: “[Eerie music plays] Jack wrapped his fingers around Patricia’s throat” while viewers went [Gulp]. Streaming videos follow the same principle. Once the user chooses to watch a film with subtitles, the streaming service pulls all the subtitle options together and displays them at once.

Yet, subtitles were used occasionally. It was used when the spouse or baby is asleep while someone else in the room wanted to watch a film. It was also popular among those who were hard of hearing.

Why blame microphones?

What changed? Television sets as well as how audio is captured. When CRT televisions were all over the place, nobody needed an extra speaker to decode what Norman Bates says in Psycho: “A boy’s best friend is his mother.” Or, Ben Braddock in The Graduate: “Mrs. Robinson, you’re trying to seduce me.”

Initially, microphones were placed strategically around the set. They were big and bulky but captured every dialogue. The sound was recorded onto hard memory like wax and then tape. Sound was recorded on one track. Every actor focused on the microphone as much as the camera. If the dialogue wasn’t picked up, the shot was taken again, increasing production cost. These days there are usually two boom microphones and each actor has at least one lavaliere microphone. Actors don’t need to focus on the mic anymore because they know all the tiny microphones will pick up the sound. It inspired a generation of mumblers. Such dialogues need to be treated in postproduction. If that doesn’t work then ADR or automated dialogue replacement comes into play. ADR costs actor’s time and it costs the studio money. Technology is used to tackle ADR, which doesn’t always help. And we forget that the volume of dialogues cannot be turned up as a solution.

The mix

This brings us to the second problem. The Vox has turned the spotlight on most Christopher Nolan films — Interstellar or Dunkirk or Tenet. Many dialogues are inaudible. “I actually got calls from other filmmakers who would say: ‘I just saw your film, and the dialogue is inaudible.’ Some people thought maybe the music’s too loud, but the truth was it was kind of the whole enchilada of how we had chosen to mix it,” he has told IndieWire.

While recording the original audio, recording mixers think of the widest sound format that’s available, like Dolby Atmos, which has true 3D sounds and up to 128 channels. At home, you can’t experience all the audio channels. Besides the 128 channels, somebody has to mix the track for 7.1, 5.1, stereo and then mono. When downmixing hits a poorly designed speaker system on the TV or on the mobile, it’s all jingle-jangle.

Thinner is not better

Then there is the problem with speakers. Old CRT TVs had a lot of space for speakers. The picture quality may not have been 8K worthy but the sound was. Nowadays, no matter the brand you choose, you will need to install a soundbar. TVs are so thin that there’s hardly any space for speakers. The tiny speakers on the TV are at the back and whatever sound it produces, it hits the wall and is then deflected to all parts of the room.

Young folks like it

Spot a young netizen and chances are that his or her iPad will have three windows open, each showing something different. To grab attention, the likes of YouTube havethe option to auto-generate captions(or subtitles). AI is put to work to translate everything that’s being said. There is a delay of a second or two but nobody cares. Many watch YouTube videos in one window with the volume turned down while making a voice call or messaging in another window. It’s just about following what’s going on the screen. “[Joey] You should scream at me or curse me or hit me. [Joey eggs on Ross] Hit me, hit me, hit me… [Ross misses].” Audience goes [Oops]

Subtitles or captioning are everywhere and the results are getting better in leaps and bounds. Once you get used auto-captioning, there’s no going back.

In May, a survey was conducted among 1,200 Americans and here are the results: 70 per cent of adult Gen Z respondents (ages 18 to 25) and 53 per cent of millennial respondents (up to age 41) said they watch content with text most of the time. Or, slightly more than a third of older respondents, according to the report commissioned by language-teaching app Preply.

No wonder, every tech biggie focuses on captioning when developing products. Pixel phones are great at auto-captioning, many Samsung TVs can automatically place captions on the screen in locations that won’t disrupt the view, Instagram generates captions on uploaded videos by default, Snapchat users can turn on autogenerated subtitles for the app’s Discover page and so on.

What remains to be seen is whether AI can take autocaptioning to the standards of Herman G. Weinberg, who translated over 300 films in the early Hollywood era. In a New Yorker interview in 1947 he said: “We’re adapters, rather than translators. We try not to lose any wisecracks, even if it means stepping up the pace, because an American will hear a couple of Frenchmen in the audience howl at a joke in French and it burns him up not to be in on it.”