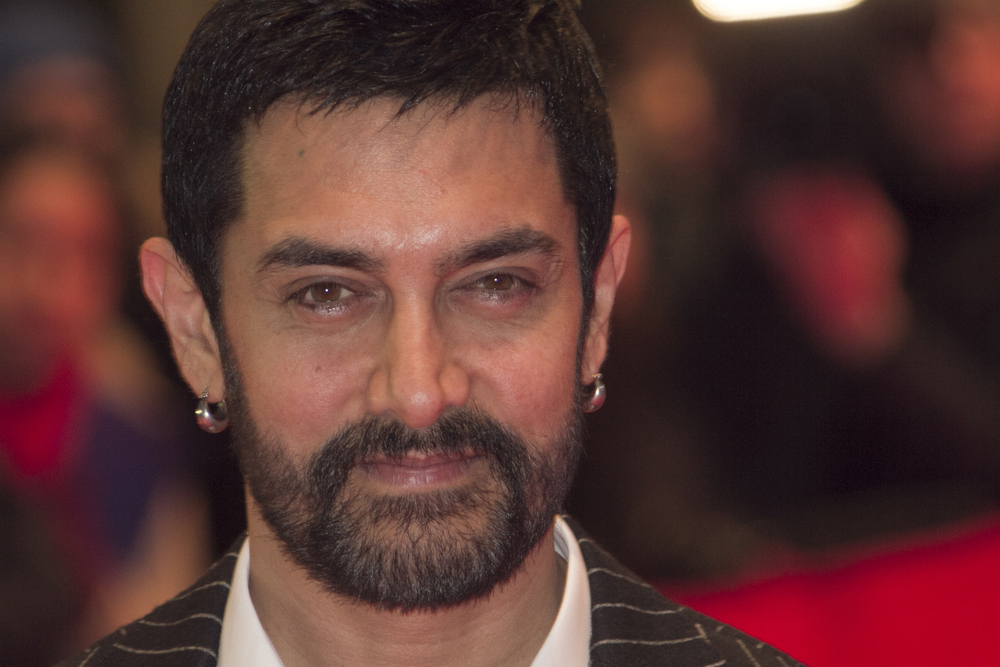

So now that Aamir Khan has stepped back into Mughal, a biopic on Gulshan Kumar, the late tsar of the music industry who was gunned down by the underworld, would it be right to conclude that the overzealous fervour with which the #MeToo movement hanged a few dozen reputations in 2018, has lost its blind blundering and may perhaps turn into a more constructive tool to correct the terrible wrongs done to women for decades?

For someone who prided himself on always doing what’s right (and polishing the image with his TV show Satyameva Jayate), Aamir seemed to have succumbed to the same knee-jerkiness as a bunch of opportunistic media personnel did.

His long-winded tweet on October 10, 2018, took the high moral ground of “zero tolerance towards sexual misconduct and predatory behaviour” and announced that he was withdrawing from a film because “it was brought to our attention” that someone he was going to start working with had been accused of sexual misconduct. He was pointing at Mughal director Subhash Kapoor, against whom a case of improper sexual behaviour was pending in court.

Although the verbose tweet said he was stepping out “without casting any aspersions on anyone”, his actions did just that. It cast serious aspersions on Kapoor’s character and tainted him deeply. Although the actor also said, “We are not an investigative agency, nor are we in any position to pass judgment on anyone — that is for the police and judiciary to do,” it was a judgment delivered in Aamir Khan’s court.

Stepping out of Mughal by spelling out his apprehensions over the director’s moral conduct was precisely what half-a-dozen channels and extremely myopic feminists had done to countless men — damn them based on the dodgy premise that a Tanushree or a Zaira was always the victim, never vicious, always the Raja Harishchandra whose every charge must be treated as an honest truth. And most importantly, it didn’t need investigation to hang the man.

It wasn’t a fair battle, and many celebrities and institutions had done an injustice to many a man in the process. In the hysteria that followed Tanushree Dutta’s somewhat loophole-ridden tirade against Nana Patekar, it didn’t seem to strike anyone that the shabby treatment of women in the past could not be corrected by throwing any man charged by any woman under the bus. How could two wrongs make a right?

But eleven months after that damning tweet, Aamir, who said he “feels differently about things now”, walked back into Kapoor’s film admitting that he’d spent sleepless nights over the fact that his action may have cost the director his right to work when he wasn’t even sure of his “guilt”. To borrow a Hindi line, Der aaye durust aaye (better late than never), I’d say to Aamir.

Saner counsel seems to prevail all around this season. Last year, this time, MAMI (the Mumbai film festival) had dropped a few films because its producers/actors either stood accused of sexual harassment (like actor Rajat Kapoor) or didn’t take the required stand in a misconduct case they were aware of in the workplace (like Anurag Kashyap). While workshops and discussions on #MeToo were appropriate, action taken against those who’d been charged (not sentenced) had seemed harshly unfair.

But, like Aamir, who’s had a rethink on Mughal, MAMI (currently going on) has also toned down its ferocity this year. What the organisers have sought from every producer is an undertaking in writing that they have an internal complaints committee in place, compliant with the POSH Act. I daresay it’s a far fairer and more effective decision than (MAMI, Aamir or anyone) taking the law into their own hands and passing a dire sentence on anybody.

Incidentally, is there a pattern and a link between Aamir and MAMI? It turns out Kiran Rao was the chairperson of MAMI last year and she was a co-signatory to Aamir’s decisions in 2018 and in 2019.

Bharathi S. Pradhan is a senior journalist and author