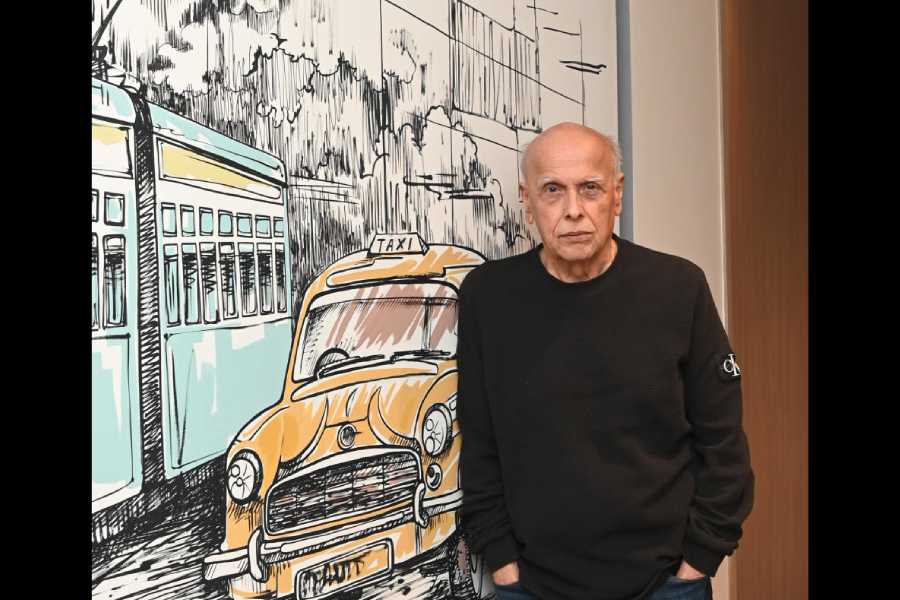

Filmmaker, screenwriter and producer Mahesh Bhatt recently made a trip to the city to be part of the inaugural session of the three-day cultural fest Khwab, presented by Sanskriti Sagar and curated by Kriti Events, in association with t2, which was held at the GD Birla Sabhaghar.

Bhatt, who engaged in conversation on the emotional complexities faced by the LGBTQIA+ community in India and their representation in the theatrical and celluloid arts with industry colleague Jayant Kripalani, later presented the play 7:40 Ki Ladies Special by Awara Group, Mumbai. The production tells the untold story of trans dancer Pooja Sharma, who catapulted to fame thanks to her dancing ability. t2 chatted with the industry veteran before he took the stage.

You’re here to speak about a serious theme and will present Awara Group’s 7:40 Ki Ladies Special to the Calcutta audience. What are you looking forward to sharing with the crowd?

The theatre movement, and amateur theatre, needs to be supported by people who have the muscle and the clout to generate funds because it’s very difficult for people who are concerned about issues that theatre deals with — and I’m talking about theatre which tries to deal with themes which are alternate, which have dissent and which clamour for social change — to get takers in the mainstream. There are stories and counter-stories being told on various platforms, there is an explosion of stories. But there’s no alternative to the body whisper. The most ancient tool of communication of man is through the body. So when a group of passionate young talented people want to get together and say that they want to do a play on an issue which is worth supporting, one stretches out and supports it wholeheartedly.

Four decades ago, I was looking for somebody to back me when I made a movie called Arth, which dealt with a very unconventional theme at the time and even now is looked upon as a pathbreaking film. But I didn’t find takers until a producer took the risk and made that film. Then I did Saaransh, and I was backed for it, though it locked horns with the entrenched values of reincarnation and spoke about finding meaning in life after death and explored relationships in your home with your partner. I think very brave people supported me. Having made a mark myself, it’s natural that as you get older you have faith in the young and you need to pass on what you have received as a duty to the young because that’s how societies survive.

In the play, what’s unique is that Pooja Sharma made a mark for herself in the 7:40 ki ladies special local train in Mumbai. She originated in West Bengal and comes from a very traditional household. She was trapped in a male body, she had this issue of choosing her identity and she battled the biases of society to finally gain support from the people in Mumbai. So it has a fairy tale element also — that if you dare to take the road less travelled, you meet fairies. You meet monsters, but you also meet fairies. She found a group of people of her kind who supported her and finally she got a dazzling spotlight when some people who used to take the ladies special recorded her on their smartphones and fired it into the landscape of the Internet and the Internet did the rest. When you touch people through your great stories, there will be some listening. The passion with which Viren and Sapna (Basoya) — people of the Awara Group who created this — was something I felt compelled to support.

I had come here previously with another play called The Last Salute. It dealt with the life story of the iconic journalist Muntadhar al-Zaidi, who had hurled a shoe at George W. Bush. We did more than 100 shows all over the country, and when I came to Calcutta, it was received very well.

I’ve been doing plays but at the amateur level because that’s where I find passion. That’s where I find it needs to be supported, in a conformist age, because the more monies are being put in the mainstream, the more storytellers are getting risk-averse. So for telling stories which are really brave and pathbreaking, you need to choose the right platforms.

Do you think the industry, be it through theatre or through film, has changed for the better?

The answer is a resounding ‘no’. There’s been a dumbing down, on the contrary. Curated content is under fire because not every platform is making money. Then you have tentpole films with a big star cast. They have people thronging to the cinema halls, but their content is of kindergarten level.

There two kinds of movies... one that jolts the comforted and the other that comforts the jolted. Content being created to numb and titillate people — it has its place — but if everybody is going to do that at every level then where is that cinema going to come from which is going to explore and speak to the real us? In this age of connectivity, there’s an epidemic of loneliness. Our living styles have changed, our homes are undergoing drastic change, we have moved light years away from what we were. These circumstances compel you to think of new stories, but not enough people are telling them.

We will need many more storytellers to dare to stand up and tell stories which connect with the times that we are living through and not lull people to sleep with their fairy tales. Storytellers need to wake you up. That is their job.

Is there a project that you feel will ‘wake up’ the audience?

Suhrita Das, my protege, has just made her first film called Tu Hai Meri Puri Kahaani which uses the idiom of a boy-meets-girl story, but deals with the very important theme of fame addiction, which is becoming an epidemic. It’s not only a curse to the people who are in the entertainment business but also social media influencers. She has dealt with that topic very seriously; it’s a very human story and reflects the time we are living in.

Anupam Kher’s Vijay 69 is wrapped in the idiom of comedy but its core is right. (Director) Akshay Roy takes you close to that individual of 69 who has almost become invisible in society… we don’t look at our elders. There are many people who live their lives and then disappear without having left a mark and there’s a thirst in them to say that they were here. When you’re young, you want to write your name on every tree and the earliest memory we all have is writing our names on the school desk. Why do you do that? You want to tell the world, ‘I was here’.

When people are old, they feel the horizon is coming closer. The feeling of having lived a worthless life tears them on the inside. The film uses comedy to lure people to come closer but packs in more serious tones. It’s like (Charlie) Chaplin — comedy is serious business. These are stories you need to tell. I wish it was released in cinema halls because only when the halls generate revenue do you have more people back in the industry.

Are there any pointers that you share with your children when it comes to their work?

I don’t advise my children at all. I listen to them more. Pooja has an exceptional track record, she was the youngest producer at 20, when she was a star, and made her first film (Tamanna) as a producer on the theme of female infanticide, for which she got a National Award. She made Zakhm, which dealt with the plural space that needs to be fought for tooth and nail, and she herself has led a very exceptional life. She spoke about her alcoholism openly and now is doing a podcast on the issue of addiction.

Alia, though she has become a very big star and is an A-lister, has an appetite for doing movies like Udta Punjab and Gangubai (Kathiawadi) — things which are audacious. Even with Jigra — though it was not a box-office success — she dared to work in a film which bypasses the traditional commercial films which compel you to do a film only when it’s got a love story. There was a love story, but with a brother.

Shaheen is a writer. She dove into her own darkness and pulled out a great book on depression. I am very proud of my daughters. I keep boasting to the world, ‘Don’t mess with me, I’m the father of three daughters.’ All my daughters are very unique and I do talk to them about things but I listen to them too.

This is the age of reverse mentoring. The elders must listen to the young because they are living in the vibrant stream of life. You need to hear them out because they know where the shoe pinches. If you listen to them, they will tell you something about the times.

But I’ve also seen that the young ones these days are a little alienated from the life-affirming values which have stood the test of time. They need to be brought back to that because stories need to do what essentially they did years ago during the time of the caveman. They brought tribes together, to sit down around the campfire to tell stories which had wisdom instilled in them. Good stories are glue which an individual pulls out from his own heart. There are certain ageless truths you have to grapple with, and tell them truthfully because only then do they endure the passage of time. Because the truth doesn’t wrinkle. It stays.