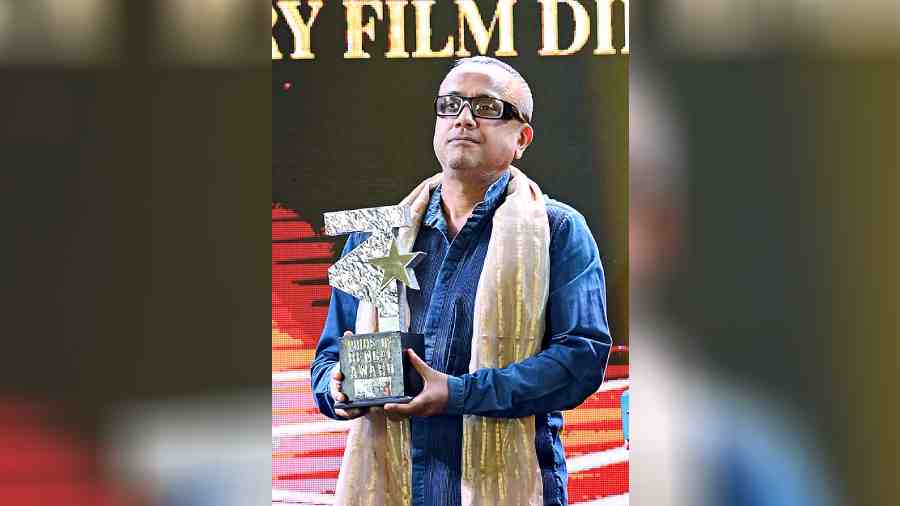

Film-maker Dibakar Banerjee was recently in town to receive the prestigious Pride of Bengal award, an annual excellence award given by the Indian Chamber of Commerce Young Leaders Forum to achievers with a Bengal connection. The Bengali born and brought up in Delhi has a vast filmography to his credit — from dark comedies like Khosla Ka Ghosla and Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! to serious drama like Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! and Shanghai. The Telegraph caught up with the multiple-award-winning director on the sidelines of the awards for an informal, light-hearted chat on his Bengali roots, his influences, his films and more.

What kind of bond do you share with Bengal? Do you have roots in the city?

To me, Calcutta has always been a city of fascination. My maternal uncle’s house was in Howrah and I remember my visits here during my holidays in the ’80s. Crossing the Howrah Bridge over the river was a big thing. I remember my visits to the Birla Planetarium, Chowringhee, and, of course, gorging on Mutton Rezala at Aminia or Sabeer, accompanied by my elder cousins, who would take me there.

Other than that, too, the city has had a deep influence on me. I read Bengali books voraciously and their stories, usually based on life in Calcutta and on its streets, had a huge impact on me. Authors like Buddhadev Basu, Satyajit Ray, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay or Sanjib Chattopadhyay or even Nihar Ranjan Gupta, all wrote about the city. So not only did I get acquainted with the contemporary Bengali literary tradition at a very young age, but I also came to know the names of the various roads of Calcutta, its lanes and bylanes, its sophisticated areas as well as its notorious neighbourhoods, which found mention in these stories. All these together created quite a romantic image of Calcutta for me that was almost like a dream. Some of this was reflected in my film Detective Byomkesh Bakshy!, which was partly shot in this city.

What era of film-making and which film-makers have been your biggest inspirations?

From my very childhood, I have been exposed to Satyajit Ray, both as an author and a film-maker. So he has obviously been an important influence and I understood a lot about movies from his works. Apart from that, I have been greatly influenced by a number of film-makers, notably American filmmakers Stanley Kubrick and Martin Scorsese, Michael Haneke of Germany and many other Korean film-makers whose films I watch regularly. Among Indian film-makers, the ones whose movies I would watch as a teenager and whose work inspired me to make movies are Ketan Mehta, Shyam Benegal, Shekhar Kapur and Ram Gopal Varma.

You have made films in various genres. Is there a particular genre you haven’t touched yet but would like to explore?

I don’t think when I start a film that I think of the genre. I think of what the film really is about and how I am going to tell it… and somehow I blunder into a way of telling it. So I really don’t know. My next film is Love Sex Aur Dhokha 2 (production of which is expected to start soon) … you can imagine what kind of telling it will have. I hope it will be something different. But let’s see. It’s also my first sequel.

Bollywood is beginning to enjoy good box-office collections again post the cancel culture phase. What opportunities does it hold for the new generation of film-makers?

Look, what we primarily need is for the theatre experience to survive and thrive and for OTT platforms to start delivering quality. If OTT platforms don’t look at quality, they will face the same crisis that cinema faced. And if the cinema-going culture does not survive, then we will walk into a monopoly of OTT platforms which won’t be good for talent and content. So the cinema-loving audience of India must want that both these survive because it’s only the lack of monopoly that ensures quality. And in India, we know that too well.

Do film-makers need to reorient their style of storytelling for the modern, multiplex audience? Is it any different when making a film for OTT?

The nature of storytelling changes every time the nature of society changes. So if you look at films down the ages, the films of the ‘70s are not made the same way as those of the ‘80s. If you look at the films made in the early 2000s, they are nothing like the films that are being made today. Sometimes I have had to pay the price for my films being slightly ahead of their time. According to me, there is no fixed formula or style for any film or any era — you just have to go ahead with what comes to your head and what feels good or correct.

What is your opinion on Hollywood’s recent recognition of Indian films?

Firstly, our way of telling stories is becoming popular because the Indian diaspora or the Indian cinema-watching audience is spreading and gaining in numbers all over the world. But what it also means is that beyond a point, we must think beyond Bollywood or Kollywood or whatever it is, and let the world see Indian stories — we need to make films based on Bangla, Marathi, Telugu, Punjabi or Hindi stories, which reflect the absolutely exciting time that India is going through, where history is changing, literally, and society is changing phenomenally.

So for me, the take is that we need to show more and more of what we are and who we are to the world, in our languages. India is almost like a small continent with so many languages, cultures and so many film industries and its diversity of audiences and styles of film-making... where else will you get all of this? That’s the beauty that the world needs to see and what we need to showcase and celebrate through our films.