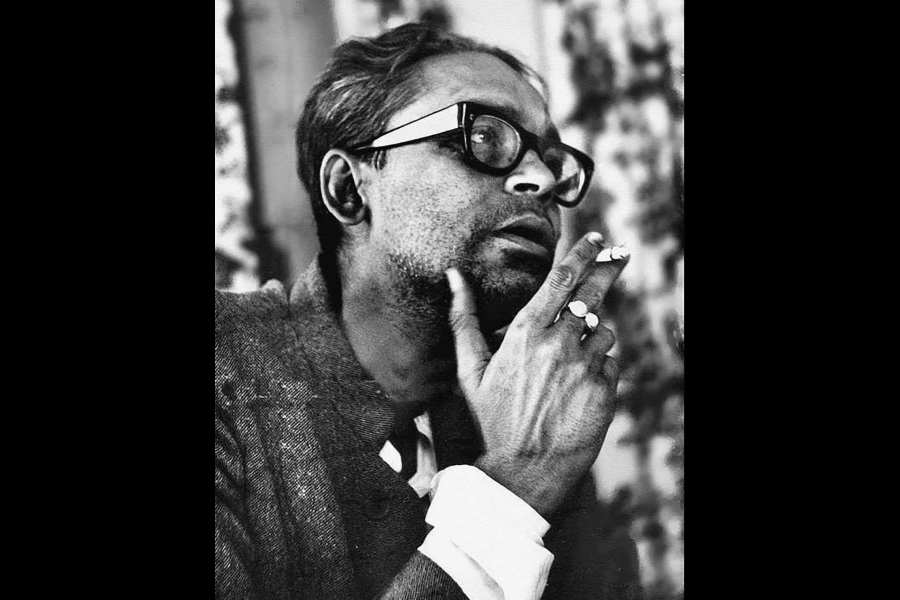

About five decades after his death, Ritwik Ghatak is becoming an “icon”. His name is being pronounced more than ever. Martin Scorsese speaks of him. Calcutta has a Metro station named after him. His gaunt face was always poster material; maybe you will now have it looking at you from T-shirts or mugs, the resting place of icons.

An occasion that may cause a flurry of such activity is at hand: the redoubtable filmmaker is going to turn 100 soon. He was born on November 4, 1925. The centennial celebrations have begun.

Which is why some are afraid. Iconisation has not always been a good thing for the icon. Tagore is proof: worship has not helped an understanding of his works. On the contrary.

A “Ritwik pujo” will be doubly tragic because Ritwik’s films have hardly ever been understood. More than iconic status, he would have liked his films to find an audience. A large one.

His persona always loomed large, though, which is part of the problem. “When he died on February 6, 1976, he was known for his eclectic creativity and alcoholism,” says Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay, former professor of film studies at Jadavpur University, Calcutta.

“Ritwik was an anti-establishment figure, a counter-culture presence for the Bengali middle class, which clubs together Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Manik Bandyopadhyay and Ghatak,” he laughs.

All three men died when they were around 50 and perfectly fit the artist’s prototype as described by Frank Kermode: self-destructive, “lonely, haunted, victimised, devoted to suffering rather than action”.

Mukhopadhyay was one of the speakers at Jibansmriti Archive in Uttarpara, about 30km from Calcutta, where Ritwik Akhra, an archive on the filmmaker, was inaugurated on April 6.

Posters of some of Ritwik Ghatak's films

The archive intends to bring together Ritwik’s films — he made eight feature films and several short ones — his writings, writings on him, posters, film-related material and everything else related to him.

The response has been overwhelming, says Arindam Saha Sardar, founder of Jibansmriti Archive. He has just been gifted a poster of Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Ritwik’s best-known film, in French. Ritwik has received considerable appreciation in France.

Artist Hiran Mitra has contributed minimalist posters based on Ritwik’s films and a portrait to the archive.

Ritwik, says Mukhopadhyay, was branded a Partition filmmaker. He did talk about the Partition, and the life of refugees in Bengal, but his "Partition films" — Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar (1961) and Subarnarekha (1962) — do not depict the Partition. They depict post-Partition trauma and alienation, says Mukhopadhyay.

Ritwik was more interested in the human predicament than in a particular event.

“This alienation takes place everywhere on earth. People are crossing borders and don’t know why. This is taking place in Palestine, on the Mexico border,” Mukhopadhyay says. Or on the borders of Europe, or Bangladesh, or India.

Crossing the border isnot just moving across twogeographically separated places, but also a question of psychic dislocation. Many of Ritwik’s characters are dislocated, homeless.

In Ajantrik (1958), the protagonist, who treats his battered taxi like a dear human companion, calling it Jagaddal, lives in a godforsaken place. Homelessness runs through Nagarik (1952), Ritwik’s first film, which was released after his death. Anasuya in Komal Gandhar is torn between places. Dislocation is a constant theme in Ritwik.

But the plot in Ritwik’s films, most stunningly, is supported by an allegorical framework, which Ritwik created by a radical reworking ofour myths.

Another exceptional aspect of his cinema was that though deeply influenced by world cinema — Eisenstein was the greatest influence on him; he rejected Hollywood and its neat storytelling — all the elements of his films remained Indian.

Meghe Dhaka Tara, the story of a refugee family, is inspired by Kalidasa’s Kumarsambhabam, which is about the union of Rudra, Shiva, the god of destruction, and Uma, the great mother. Their union will lead to the birth of Kumar, who will destroy evil.

But in the crisis that is contemporary reality, this union is not possible. So Rudra and Uma — Shankar and Nita here — are brother and sister. Yet the film re-enacts the myth, coming into focus sharplyas Shankar sings “Je raatemor duarguli” with Nita joining him. The song itself created history by introducingthe sound of a whip to a Tagore song.

“The song accomplishes the journey between the timeless and the temporal,” says Mukhopadhyay.

In the darkness the camera focuses on a stretch of Nita’s neck. It is long and curved like the neck of the idol of the goddess. The camera moved between seeing and losing the brother and sister. When they cannot be seen they seem to become part of a mythical time. And then Nita’s face, shot at an impossibly low angle, fills the screen. Her eyes are looking elsewhere. A strange light falls on her face.

This is the moment before bisarjan when the goddess is floating, just before drowning. The goddess, or the daughter of a refugee family who has looked after everyone, has been sacrificed. This is the trauma of Indian history. Nita’s cry, “Dada, ami banchbo (Dada, I want to live),” is a cry of the heart that is at the heart of all of Ritwik’s works.

The story of Shakuntala is a leitmotif in Komal Gandhar, with a comparison with Shakespeare’s Tempest implicit in it, says Mukhopadhyay.

Ritwik was saying that in Western art, nature helpsthe movement of the plot, but you cannot displace Shakuntala, take her out of the tapoban, nature.

In Subarnarekha, Kaushalya, “Bagdi bou”, a lower caste woman, dies uncared for at a railway station even as her son, Abhiram, who was separated from her many years ago, happens to be present there that very moment.

Abhiram’s wife is Sita. An epic has got rewritten for contemporary India.

Mythical creatures disguised as humans travel across Ritwik’s landscape. “A philosophical argument isat the heart of Ritwik’s films. He is the most cerebral among Indian filmmakers,” says Mukhopadhyay.

But when the films were released, they were a bittoo much for an audience brought up on films as entertainment and on a certain kind of realism.

Ritwik did not care for realism, or for Hollywood and its storytelling. “He introduced a discursive cultural practice that transcended plot or narrative,” says Mukhopadhyay.

For Ritwik, even film as a medium did not matter. In Cinema and I, a collection of his remarkable writings and interviews, he says: “Cinema for me is nothing but an expression. It is a means of expressing my anger at the sorrows and sufferings of my people.”

Had he found a medium with greater force and immediacy to communicate, he would have chosen that.

An archive will be a reminder of Ritwik. Artist Mitra, who has long been part of the film club movement and was present at the inauguration, feels Ritwik is a weapon against contemporary culture, which is a lack of culture, or the opposite of culture. “We had been burnt by him in our youth,” he says.