The author is a Delhi-based freelance writer and critic who writes mainly about books and films

1968 was an important year for pop-cultural interactions between India and the West. It was the year of the Beatles’ celebrated White Album, which came out of a Rishikesh visit during which they were enthralled by and then disillusioned by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.The George Harrison-Ravi Shankar musical association would be more long-lasting,and was alluded to in the Merchant-Ivory film The Guru, released early in 1969. Meanwhile the Hindi film industry had been throwing money into glossy international productions like Around the World, An Evening in Paris and Aman, almost as if to pre-empt the Beatles’s visit and to present a view of the Indian as global citizen.

This was also the year in which Peter Sellers played an Indian named Hrundi V Bakshi, intoning “Birdie Num Num”, in the slapstick comedy The Party.Watching The Party, Satyajit Ray – who had recently been in talks with Sellers about a science-fiction script– noted the scene where Bakshi refers to “my pet monkey Apu”, and wondered if it was a dig at Ray’s famous trilogy.

But another major Hollywood star – whom Ray had also met in connection with his sci-fi story –played an Indian that year too, in a film so strange that it can make The Party look like a kitchen-sink drama. In the final act of the sex satire Candy, Marlon Brando appears as a lustful “gooroo” who explains to the titular heroine that the Y in her name stands for Yoni. It’s an impressive monologue, but he has trouble managing his yogic sitting posture; like the mad scientist in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove, wrestling with his own arm as it tries to give a Nazi salute, this guru grunts and writhes as he tries to lock his knees in position. His white dhoti rides up to reveal his powerful thighs. This is nothing like the sensuous, vulnerable young Brando of A Streetcar Named Desire and Julius Caesar, but it’s pretty sexy in its own way.

Based on a novel co-written by Terry Southern (whose most famous film contribution, as it happens, was the screenplay for Dr Strangelove), Candy is about a nubile young girl drawing the lustful attention of a line of (mostly middle-aged) men from different walks of life: gurus, yes, but also doctors, a military man, a highbrow writer, a mountebank, and her own uncle (John Astin, in what may be the film’s most unselfconsciously funny performance).

And that’s really all there is to the “plot”.This film is a series of skits built around a one-note situation – “respectable” men turn into satyrs at the sight of Candy – which it uses to satirise everything from xenophobia to jingoism to democracy to the hypocrisies inherent in human nature. A Welsh poet (played by Richard Burton) speaks in the anguished tones of a tormented creative person even when he is doing nothing more profound than reciting the address where the money order for a copy of his book is to be sent. A famous doctor performs a ticketed surgery to which his audience comes dressed as if for the opera; while slipping his gloves on, he casually gropes the nurse holding them out for him. A Mexican gardener (played by Ringo Starr, as if one Beatles reference weren’t enough for this post) is held back from Candy-worship by his three domineering, Fury-like sisters.

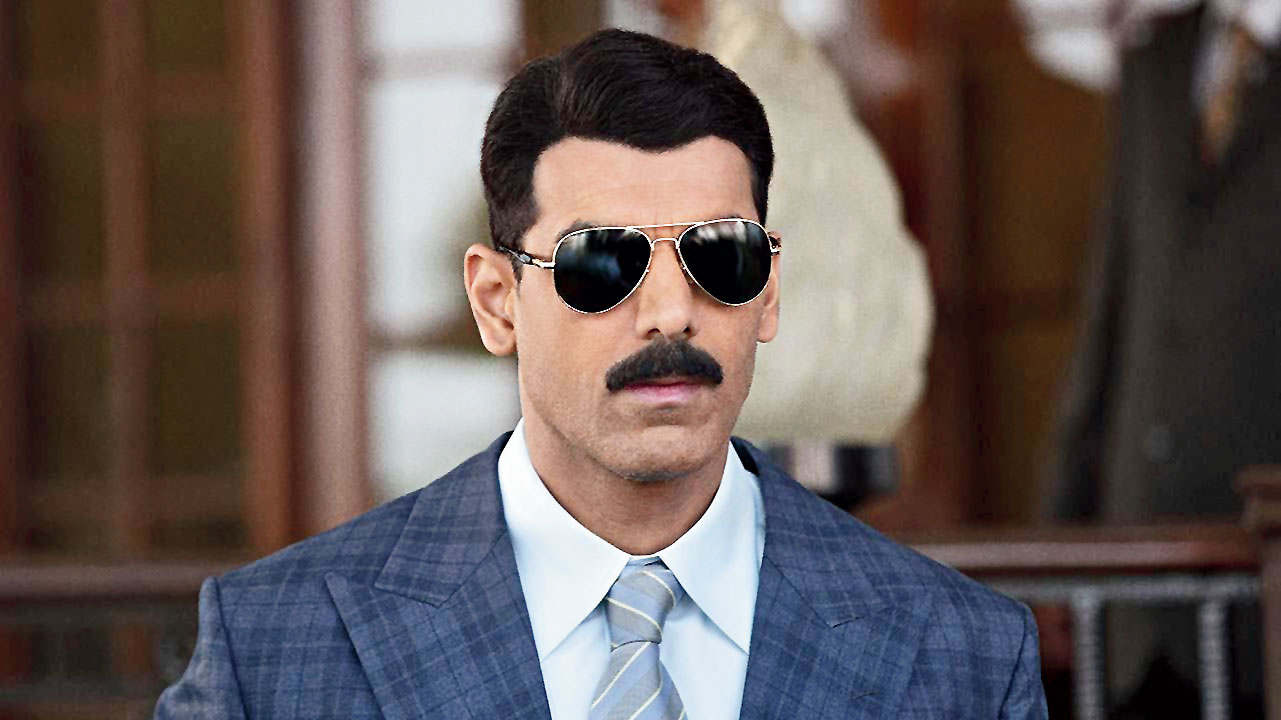

Brando’s performance blows hot and cold (he appears to make a stab at a sing-song Indian accent early on, but soon discards the idea) A still from the 1968-film Candy

This is nothing like the sensuous, vulnerable young Brando of A Streetcar Named Desire and Julius Caesar, but it’s pretty sexy in its own way A still from the 1968-film Candy

All this lunacy leads unerringly to the Brando sequence, which begins when poor Candy clambers onto the back of a huge trailer truck and discovers a mystical, watery chamber (with little kettles dangling from the ceiling, and oyster shells on the walls) wherein the holy man sits meditating. When he gets an eyeful of her in her flimsy dress, it’s enough to have him spouting gobbledygook about the many stages of becoming one with the universe. In addition to words that are familiar in the India of today: “You must leave science behind,” he says, “It is corrupt.” Because all truths, and technological advances,are to be found in the ancient wisdom of the East, and the West simply hasn’t caught up yet. (Never mind that this truck is heading determinedly westward, across the American heartland.)

In some obvious ways, Candy is a dated work. It’s a film of the hippie moment, with psychedelic music and images that belongs firmly to a period that saw the release of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and the Pink Floyd album A Saucerful of Secrets. It may have appealed to the same viewers who lay, drug-addled and mumbling phrases like “transcendental consciousness”, on the floor below a movie screen while 2001’s Star Gate sequence swept over them.

Candy is also a little vulgar and exploitative in places, begging the question: can a film that satirizes pornography and male sexual aggression avoid becoming sleazy itself? (Consider that the Lolita-like Ewa Aulin, constantly leered at by the camera, had just turned 18 when she played the title role.) And of course, it is offensive (if you relish being offended) to various groups. Doctors. Patriots. Poets. Hunchbacks. Mexicans. Sadhus. Families. Women. Men. Take your pick.

The biggest problem with the film though is that it isn’t funny enough on a sustained basis – too often, it feels tired and stretched out. But if you can work your way through the duller or forced bits, there is a savagely matter-of-fact satire about the worst impulses of people; about how powerful men, across milieus, can be predators. And in the process, it allows for some respected male stars to be undignified in front of the camera, even to send up their own personas.

Of course, no actor worth his salt should be permitted an ego about what he will or will not do onscreen – but even so, it seems to me that some of the thespians in Candy go beyond the call of duty. It’s particularly impressive to watch Burton (a dashing, golden-voiced, classical British actor) play a transparently hypocritical poet who starts off behaving like a cool, modern-day Lord Byron but turns into a double-entendre-bellowing drunk when he has Candy alone with him in his car. (“Can you withstand my huge… NEED?”) Or to see the always-elegant, catlike John Huston as a hospital administrator who loses control.

As for Brando’s performance, it blows hot and cold (he appears to make a stab at a sing-song Indian accent early on, but soon discards the idea) and it is all too easy to mock him for this role, to set it unfavourably against his major canonical parts. But there are times when he is genuinely funny, showing a knack for physical comedy (don’t miss his last appearance, where he catches a glimpse of Candy while being suspended in the air from ropes) as well as a piercing, rugged faux-intensity. It’s almost enough to make one wish Hollywood had made a DeMille-style epic around India mythology and cast him as Lord Shiva, holding out his gaanja to asuras and apsaras, making them an offer they couldn’t refuse.