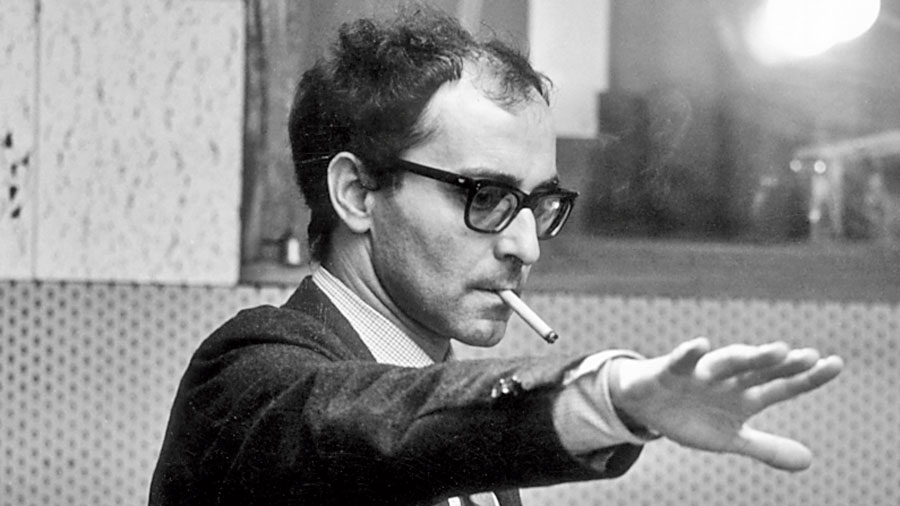

I wasn’t prepared for Jean-Luc Godard; I doubt that anyone ever was. And now that he’s gone, it feels impossible to articulate the immensity of his impact on cinema, an art that he changed more than most. His influence was profound, so much so that even after his work fell out of favor and was reflexively dismissed by the lazy, and even as he himself faded (he died by assisted suicide Tuesday at age 91), vestiges of this vexing giant, the cool guy with the dark sunglasses and cigar, remained. He was a phantom of cinema long before his death, and he will haunt us.

When we speak of adored artists, we often flash on the first time we encountered their work, a tendency that evokes first love. I was in college when I saw my first Godard film, Every Man for Himself (1980), widely considered a return to form. I can’t remember now what I thought of it then. I only remember the sensations that it produced as I reeled from the Bleecker Street Cinema and walked home in a fog, dazed. I thought that I understood movies, but I didn’t understand this one. What I also didn’t understand is that I had just watched another way of making — and seeing — film.

Early on, Hollywood made movies easy for us. It taught us how to understand its sense of time and space, and it turned sights and sounds into stories. It invited us in with a smile and instructed us to enjoy the show, then come back for more of the same the next week. Godard didn’t make it easy, or not always. He insisted that we come to him, that we navigate the densities of his thought, decipher his epigrams and learn a new language: his. If we couldn’t or wouldn’t, too bad — for us. We were the ones impoverished for not seeing that cinema can be more than laughter and tears, dollars and awards.

That movies can also be more than moneymaking machines, anything other than corporate brands, sounds quaint in the age of Marvel — terribly old-fashioned, naive. It’s striking and instructive that now when a new movie arrives that genuinely excites people, there may be some chatter about its representations and whether it conforms to established ideas about correct politics and entertainment. Invariably, though, the greatest focus will be on its box office potential and concomitant Oscar chances. Turning movies into commodities is the other way that Hollywood made it easy for us.

A scene from the film 'Every Man for Himself' Twitter/ @RowanAmberMill

It could be so much more, as Godard showed decade after decade. Cinema is art — or can be — and it’s political, as he also insisted. That was clear from the beginning of his movie life first as a critic and then an artist. But there was such joy and youthful romanticism in the earlier work that it was simpler to vibe on its pleasures than contend with its complexities. The reason I fell in love with his 1966 film Masculin Féminin when I first saw it wasn’t because he described his characters as “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola”; I fell in love because I too was young, and it was beautiful, and it broke my heart.

In time, I learned how to watch Godard, though in truth, I think he taught me how to watch. An early exposure to avant-garde cinema helped me in this simply because by the time I started digging into Godard’s work, I already knew that movies didn’t necessarily have to be obvious. Sometimes, you needed to puzzle through them; sometimes, you need to get lost. There’s immense pleasure in getting lost in movies, in letting the at times excitingly, bafflingly unfamiliar wash over you, letting the images and sounds sink into your body as your mind tries to comprehend what’s happening.

One of the things I find most moving about Godard is that even as movies changed, he did, too. He worked in television before it was acceptable for serious filmmakers to do so, and when the movies went digital, he did as well, finding new and shocking beauty with it. He smeared colors and made them pop, playing with his new media tool kit with the giddy inventiveness of someone just discovering his own brilliance. In his 2014 movie Goodbye to Language, he dabbled in 3D, showing me images I had never seen and haven’t seen since. Watching it at Cannes, where attendees cheered and nearly levitated out of their seats, remains one of the great experiences of my moviegoing life.

Scene from the film 'Masculin Féminin' Twitter/ @MotionPictureQ1

Godard became disgracefully marginalized, relegated to the festival circuit and negligible theatrical releases. And in contrast to his longtime compatriot, Agnès Varda, who became more celebrated as she aged, he receded from public view. Their relationship plays a role in Varda’s 2017 essay film, Faces Places, a meander through history and memory that she made with the artist JR. At the end of the movie, Varda and JR show up at Godard’s house in Rolle, Switzerland. It’s been years since she has seen him, but Godard refuses to come to the door or even acknowledge their presence, causing her to weep.

I’ve always thought the real reason Godard didn’t come out to say hello to Varda was that he didn’t like or respect JR. JR helped Varda enormously, but his work isn’t on the same plane as either hers or Godard’s. Even so, the old man could have come out to say hello to his friend. He could have whispered a simple bonjour through the door in his distinctive gravel. But Godard clearly wasn’t interested, and unlike Varda, who charmed admirers who too often mistook her for a cute old lady, he didn’t play the game.

He didn’t have to. Varda was a woman in a man’s world, and she learned how to work the room, a habit — and burden — that wasn’t necessary for Godard, the onetime enfant terrible, the former bad-boy genius of cinema who faded into a caricature of himself, almost Lear-like: “A poor, infirm, weak and despised old man.” Godard played with that image of the gruff, cranky, cigar-chomping guru of cinema’s past, while in reality, he remained a prophet for its still-unrealized future. Despite his reputation and all the scandals, the cynical aperçus and stinging air of pessimism, he was an astonishing optimist.

A few years back, a friend sent me some Google map coordinates, excitedly telling me that if you clicked on them, you could see Godard walking along some Rolle streets with Anne-Marie Miéville, his third wife and frequent collaborator. I clicked on the link excitedly, and there he was, caught midstride, his face blurred yet distinct and recognizable in the bright, sun-filled images. He was wearing dark clothes and carrying a light-colored plastic bag. At one point, they appear next to a red car, and I flashed on all the cars and colors in his movies. It was so ordinary, yet so extraordinary. I like to think that he and Miéville had just gone out shopping. I hoped that they were happy. In one way, I had found Godard, but really, my search will never end.

The New York Times News Service