Vulnerability. Culture has taught us that to be a man is to project toughness. It’s another way of asking us to sweep weakness and vulnerability — the uncomfortable, inconvenient truths — under the rug. Seventy years ago, Charles Schulz dared to focus on issues of insecurity, inferiority and tenderness through some sharp observations in his creation, Peanuts. He was, in a way, a rebel as comic strips largely didn’t dare make such issues its lifeline.

“I have deep feelings of depression,” round-faced Charlie Brown — looking vulnerable as always — tells Lucy at her psychiatric help stand, only to be told: “Snap out of it! Five cents, please.” No doubt, such sparks of creativity endeared Charlie Brown and his gang to us as much as their creator.

Named after the horse Spark Plug in the comic strip Barney Google, he was and will always remain Sparky to his loved ones. “The first thing we always describe is the humanity of the characters. Each character represents a human personality with all of its complexity but also with its endearing quality, so it’s very human. Sparky would say, ‘Don’t forget the art.’ Every panel has to be beautifully drawn and executed. I think the humanity is in the strip, in the stories of the strips, in the way that characters interact with each other, and it’s very true to life. It’s true that people see their own childhoods and their own lives in the strip,” says Jean Schulz, the legendary cartoonist’s wife, over video chat with The Telegraph.

Jean Schulz Getty Images

here was — in some ways, an absence of certainty in Charles Schulz as much as in Charlie Brown. “There is a Sunday page in which Charlie Brown says ‘I don’t like to be happy; I’m afraid to be happy. Lucy, who’s in the psychiatrist booth, says, ‘Why should you be afraid to be happy?’ He says, ‘Every time you get too happy something bad happens.’ So she says, ‘You’re sitting there. Are you happy?’ Charlie Brown says ‘Ya, I guess I am happy.’ And then he falls off the chair,” the late Charles Schulz had said in a television interview.

At its heart, a story of friendship

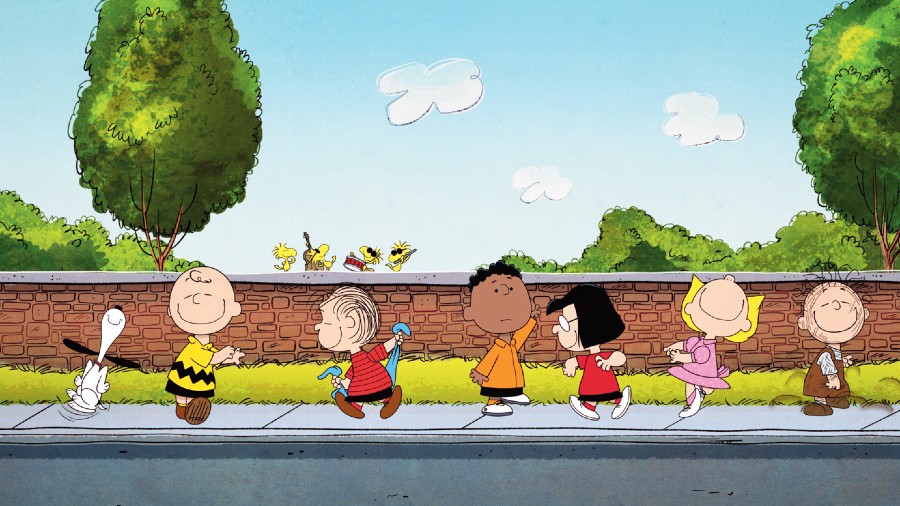

A sizeable part of Charlie Brown is Sparky, and the rest, his imagination. Keeping the lovable character company in a nameless American suburb are his loveable dog Snoopy, the always blunt Lucy, her blanket-clutching brother Linus, Beethoven-adoring Schroeder and so many other kids but never any adults.

Peanuts is a story of friendship, something that remains a cornerstone of American culture. Sparky ensured that Charlie Brown and friends spoke for people everywhere in America and not just a generation. While creating the comic strip little did he know that the theme would be appreciated around the world.

“We have often wondered how people relate to it in different cultures. There is a sort of common humanity in the characters that almost any culture can understand. People may not understand every situation that the characters go through, but they can relate to brothers and sisters and friends in the neighbourhood and the dog,” says Jean.

No wonder, the new animated series, The Snoopy Show, on Apple TV+, is being embraced by a global audience. It’s a show that mines stories from the 18,000-odd strips that Sparky has left behind. Adhering to the craft of the creator, viewers can identify with every story in the series, be it the way Snoopy meets Charlie Brown, kites getting stuck in trees or Lucy’s psychiatric booth in operation.

In 2021, The Snoopy Show comes across as a breath of fresh air as children’s TV continues to remain largely predetermined, cramped with superheroes and flying cars. The Apple TV+ show questions the meaning of life itself, like Charlie Brown and his pals did in the comic strip that ran in more than 2,600 newspapers, reaching countless readers in 75 countries.

“I would like to say that I think we’ve been waiting for 20 years since my husband died to see an authentic description in animation of what’s on the comic page. So we’re very happy,” says his wife Jean, of the show.

She says it’s the artwork of her late husband as well as “cleverness of translators” that worked wonders for Peanuts. “Sparky used to wonder how they translated some of the comic strip, because some things don’t translate. For example, baseball. There are 3,000 baseball strips, but baseball doesn’t translate in every culture. I mean, they play football a lot more. I think part of (the popularity lies) in the translation. It depends on how it was translated and the cleverness of the translator. And then he would say, the art. It was pleasant to look at. Snoopy is sort of universal, people can enjoy Snoopy without any context, because he does funny things — he jumps and dances and pretends he’s a vulture and then pretends he’s something else. Snoopy has his own life. I think that Snoopy has often been the (entry point) of the comic into other cultures.”

Sourced by the correspondent

Life beyond newspapers

As much as the comic strip in newspapers, Charlie Brown and his pals have been winning over television viewers for decades. The 1965 special, A Charlie Brown Christmas, is a classic. What began with a lot of trepidation, wondering how a comic strip would translate on screen, has now become a holiday tradition. It gave the lovable gang a life beyond the print medium.

We asked Jean about Peanuts living beyond the newspaper. “We recognised that newspapers were becoming fewer and fewer. Television, and now I suppose it’s television and films, and all the electronic media… we realised that was the way it had to be presented in order to not simply go away. It’s interesting because I often think about Alice in Wonderland. That is more than 150 years old and I believe that it has been in movies and so forth. People (still) understand many of the things… going down the rabbit hole and the Queen of Hearts… and all of the things in Alice in Wonderland. I don’t know how that’s stayed alive but I think we knew that animation and something that people could access on their phones and their iPads and whatever else they have, was the way to keep it alive. At the same time, it had to be kept alive by being authentic to the comic strip. Otherwise it didn’t interest us.”

The innocuous humour of Peanuts is reflective of its creator. The characters are decent and caring, also like Sparky. “He wasn’t what you would call a ha-ha funny person, but he always had a funny take on things. He had a funny way of looking at life and it was always different from the ordinary comedian. His humour was much more subtle and it might be just a word or two that he would say. You either picked it up or you didn’t. It wasn’t important to him to have people laugh at what he had said,” says Jean.

All that mattered was whether readers recognised themselves in the characters. “When he went to see You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, and sat in the audience in San Francisco, he said it was wonderful to hear people laugh at his lines from the comic strip. He said, ‘I sit alone in my room and I draw these pictures and I draw these characters making all these statements.’ He said it was wonderful to listen to people laugh at his lines, at his jokes. He was appreciative of an audience, if you will. But if he said something funny, he didn’t expect people to make a big thing of it, it was always very subtle and very quiet.”

In Peanuts we find a sense of continuity, something readers appreciate. Yes, we like enjoying the same jokes over and over again but also, there’s the realisation that there are other jokes in the strip. “The variety of his stories, the variety of the situations, and the authenticity of the strip made it special. And then Sparky would say, ‘Don’t forget the art’. Each panel has to be pleasing to look at. When he did a comic strip, he looked at spatial dimensions, the spacing, the size of the characters as it moves through the panel…. There’s a lot to the art.”

Sourced by the correspondent

The amount of effort that went into drawing each strip was enormous. Charles Schulz had perfected it to the point that it went beyond the American boundaries. Look at Peanuts in Japan where poet Shuntaro Tanikawa has translated Peanuts when it was first in the newspapers in Japan. Such has been the success that many Japanese feel that Peanuts is “part of their culture, a part of them”.

The Snoopy Museum in Tokyo appreciates every character that has appeared in Peanuts, even Faron, the cat belonging to Frieda. “They have a plush character in the gift shop. They love all the characters, even if they are not developed a lot in the comic strip.”

This brings us to the question of what the cartoonist thought of cats. Faron appeared briefly in 1961. “I don’t think he had anything against cats and he had a cat in the comic strip for a little while. The cat’s name was Faron. There was a musical star named Faron Young. But I don’t know if the cat was named after Faron. It’s a little before my time, but he said when you put a cat in the strip, it turned Snoopy into a regular dog and Snoopy couldn’t be a regular dog,” says Jean.

Of course, Snoopy is anything but a regular dog. The moment Charlie Brown met Snoopy at the Daisy Hill Farm, it was magic. The beagle ended up sleeping on top of the dog house, allowing his imagination to take wings. In some ways he is the opposite of his caregiver. Snoopy can hit a homerun in baseball, loves art and is well-versed in Leo Tolstoy. Yet, the two are also the same: both spend nights under a blanket of fear of their own vulnerability.

Year after year, Charles Schulz spent the better part of his day bringing to life all the characters, while eating English muffin with grape jelly and drinking coffee. At the same time, he was appreciative of the work of fellow cartoonists. Had he been around, would he appreciate graphic novels? “Graphic novels were just beginning to be on the scene. I think he would be delighted, actually, that people were able to draw cartoons and draw funny and get them published.”

Peanuts is about telling simple truths in a world that can be sweet and disappointing. “I don’t know the meaning of life. I don’t know why we are here. I think life is full of anxieties and fears and tears. It has a lot of grief in it, and it can be very grim. And I do not want to be the one who tries to tell somebody else what life is all about. To me it’s a complete mystery,” Charles Schulz had told Eugene Griessman in 1981. The words came from a man who simply wanted to live on as a one-word signature on his comic strip.

In a strip from March 1969, Linus and Lucy are at ‘the wall’. Lucy complains: “I have a lot of questions about life, and I’m not getting any answers!” She adds: “I want some real honest-to-goodness answers. I don’t want a lot of opinions… I want answers!” The answer came as a question that can only give way to more questions: “Would true or false be all right?” That’s life. That’s Peanuts. Happy 70th anniversary.

The Snoopy Show is currently streaming on Apple TV+

Peanuts timeline

Sourced by the correspondent

November 26, 1922: Charles Monroe Schulz was born at 919 Chicago Avenue South, #2, Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Dena Bertina Schulz and Carl Fredrich Augustus Schulz.

1934: The Schulz family was given a black-and-white mixed breed dog named Spike. Less than two years later, Spike would become the subject of Schulz’s first published illustration and over a decade later would become the inspiration for Snoopy.

October 2, 1950: The first Peanuts comic strip debuted in a four-panel format in seven newspapers in the US — The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, The Minneapolis Star-Tribune, The Allentown Call-Chronicle, The Bethlehem Globe-Times, The Denver Post and The Seattle Times. Schulz was paid $90 for his first month of strips, which consisted of a six-day-per-week, Monday-through-Saturday, format until 1952.

April 1965: The Peanuts characters appeared on the front page of Time.

October 1965: One of Snoopy’s most iconic and popular personas — the World War I Flying Ace — makes his debut. Wearing his flying cap, goggles, and a scarf, the Flying Ace rides in his Sopwith Camel (aka Snoopy’s doghouse) and takes to the skies to dogfight against the infamous Red Baron.

December 9, 1965: A Charlie Brown Christmas, the first Peanuts animated television special, premiered on the CBS network. The production team included producer Lee Mendelson, animator/director Bill Melendez, and writer Charles Schulz. Jazz musician Vince Guaraldi composed and performed the score. Schulz received an Emmy nomination for Special Classification of Individual Achievements, and the programme won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Children’s Programme.

1968: Schulz received what he considered a great honour in 1968 when he was approached by NASA to use Snoopy in the Manned Flight Awareness Programme. Snoopy’s likeness was used in many workplace motivation posters, on patches and decals, and on the Silver Snoopy pin. The following year, NASA astronauts named the Apollo 10 command module Charlie Brown, and the lunar module, Snoopy.

June 22, 1970: Woodstock, Snoopy’s loyal feathered friend, is named.

September 1973: Charles M. Schulz married Jean Forsyth at their home in Santa Rosa.

1987: Schulz is inducted into the Museum of Cartoon Art Hall of Fame and awarded the Golden Brick award.

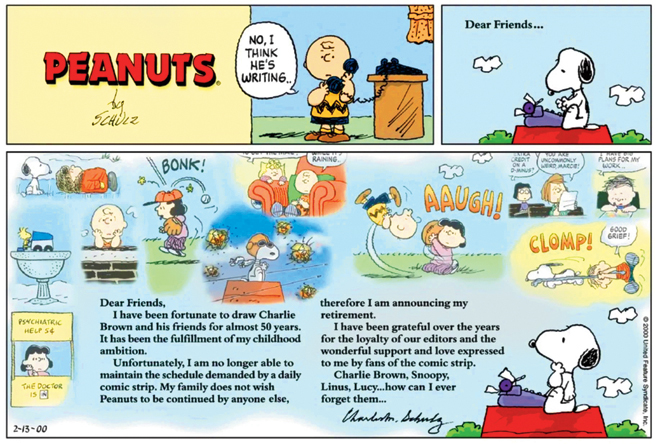

February 12, 2000: Charles Schulz died peacefully in his sleep at home, succumbing to complications from colon cancer. The final Peanuts Sunday strip appeared in newspapers the very next day, Sunday, February 13.