The irony of it all.

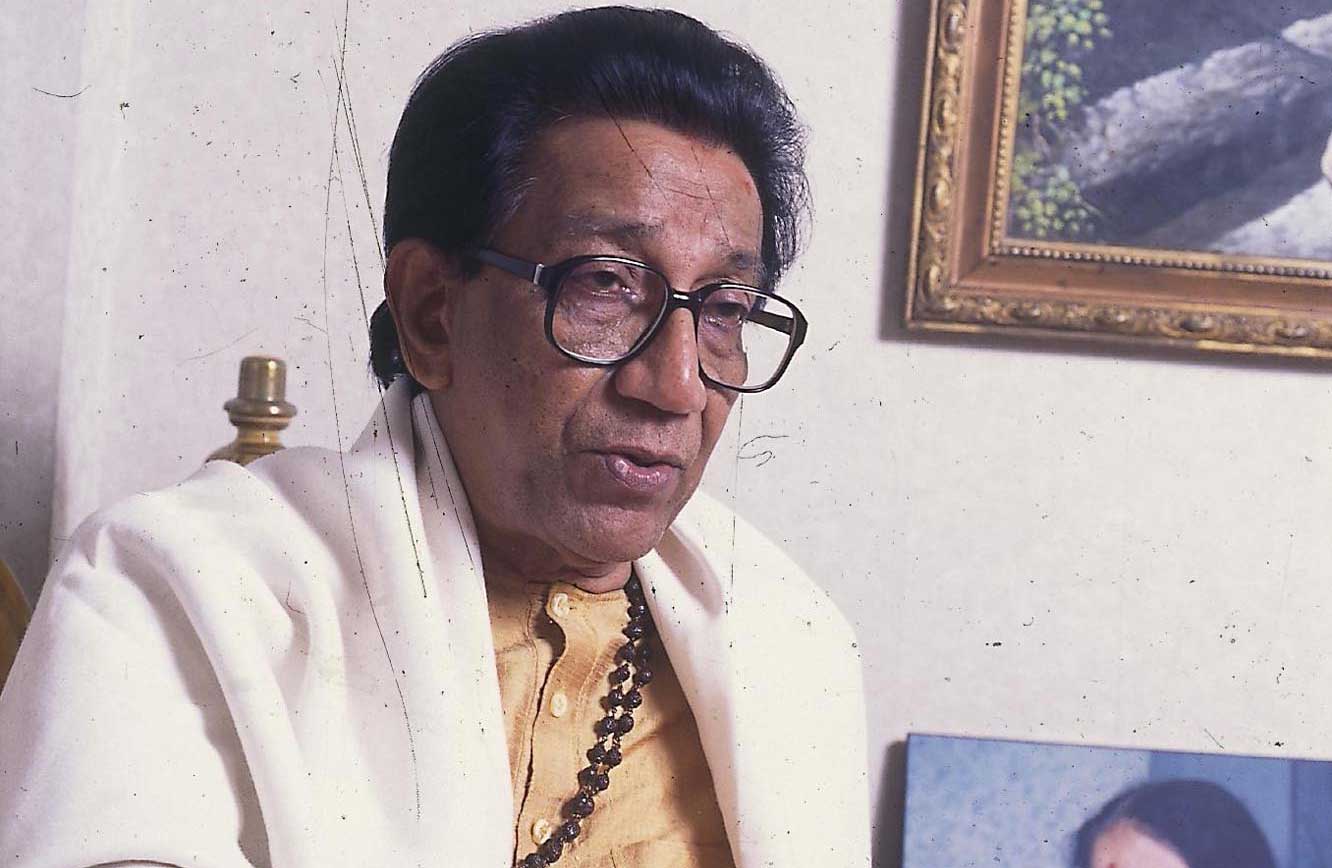

A few years ago, Nawazuddin Siddiqui was forced to step down from a Ramleela event after the Shiv Sena objected to a Muslim playing a Hindu character. In Thackeray, released last weekend, Nawaz slips into the robes of the Shiv Sena supremo in a film that traces Balasaheb Thackeray’s meteoric rise from a free-thinking cartoonist to one of the most powerful leaders in Indian politics.

Nawaz is the beating heart of Thackeray, turning in a performance as impactful as the one in Manto, the Nandita Das-directed biopic on the fearless writer that released to critical acclaim a few months ago.

Thackeray, however, is no biopic. Hagiographic in tone and treatment, the 138-minute film depicts every aspect of the man — from Thackeray to ‘Tiger’ — and peels his life threadbare, warts and all. Except that the warts are either glorified or glossed over and every illegal and criminal act that was carried forward in Thackeray’s name is given some kind of backstory, most of which are lame excuses to justify his divisive politics.

Which isn’t surprising given that Thackeray is produced by Shiv Sena man Sanjay Raut and directed by Abhijit Panse, a member of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena, that’s headed by Thackeray’s nephew Raj. The significance of the film releasing in election year is also not lost on the audience.

Judging purely as a film, Thackeray is well made, with all the significant developments in the man’s life and career being depicted impactfully, but in a linear fashion. It seems the director had a checklist in hand — Thackeray’s sensitivity towards his own Marathi manoos (“Marathi manoos ghaati hoga lekin ghatiya nahin”, is the belief that spurs his initial political stand), his love for cricket, his long-standing feud with former Prime Minister Morarji Desai and his involvement in the Mumbai riots of 1992-93 — and he kept ticking off the boxes. The result is a film that interests intermittently, with the bit set in present day — where Thackeray is made to stand in court and defend himself and his actions — pumping in some adrenaline whenever the film goes limp.

Cinematographer Sudeep Chatterjee is the other hero of the film. Most of Thackeray is shot in black-and-white or sepia tones and the initial hour has quite a few scenes where the characters leap off the screen as a cartoon strip, in the way Thackeray imagines them to be. Some familiar episodes — like his famous meeting with Pakistani cricketer Javed Miandad or Shiv Sena workers vandalising the Wankhede pitch before an India-Pakistan match in the early ’90s — bring the film to life, but only in parts.

In its bid to glorify its protagonist, Thackeray is often confused in what it wants to say. While a large part of the film has Thackeray launching planned attacks against “outsiders” in Mumbai — cinemas screening Hindi films are defaced and Udipi eateries are forced to shut down — the last hour frequently has Thackeray mouthing, “Main Hindustani pehle hoon, Marathi baad mein”.

Thackeray’s politics of violence is constantly romanticised, with more than one scene showing that most of his barbaric actions were reactions to the interests of his community being harmed.

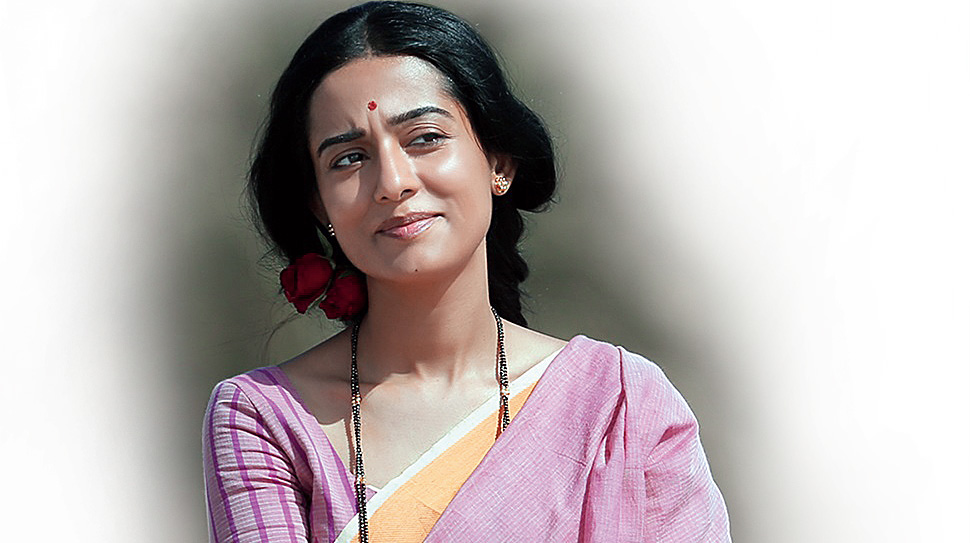

With Nawaz leading from the front, there is very little scope for the other actors, most of which are unfamiliar faces. Amrita Rao plays Thackeray’s wife Meena with restraint, but the character is uni-dimensional.

Thackeray ends with the promise of a sequel, which left us in two minds. While we are intrigued to see more of the man come alive on screen, can we do with a little less whitewashing of the man in the saffron robe?