One of the popular questions we were expected to answer in the geography exam in Class V was, “Why is Africa called ‘the dark continent’?” To be fair, though, it was not just our English-medium missionary school established by colonial Methodists a century-and-a-half-ago that favoured this question, but almost all middle-school geography students were supposed to know the answer to this, along with the position of the Nile and the Niger, which they ought to be able to mark out in blue crayon on a blank map of Africa, as well the Cape of Good Hope that had provided a pit-stop for Vasco da Gama on his way to India.

In those days I was the prissy annoying type, jumping up with the answer to everything. So I would parrot the reasons in the order preferred by our teacher: Africa has been called the dark continent because...

1. Not much was known about the interior of Africa until the Europeans arrived.

2. Less sunlight enters the thick tropical forests with their dense undergrowth, so it is literally dark.

3. The complexion of the people (with a repetition of the sentiment on the tropical sun).

4. The ignorance and disease and lack of “civilisation”.

As I type out this part, I shiver in embarrassment. I nearly reach above and erase these blithe lines which record what 50 of us wrote in our exam papers that year. But that would not alter the truth, the momentous erasures of history trapped in every word of that wretched answer, the schoolgirl versions of colonial propaganda that passed for knowledge. Possibly still does.

The only resistance against these half-truths is recorded in the deeper and more abiding testaments borne in literature. Through this literature, I can remind myself and others who, like me, parroted half-truths in geography and history exams in middle-school, but who, unlike me, travel on work to Africa today — as IT consultants, brand managers, architects, bankers and corporate farmers and investors — of alternate ways of interpreting the complex, often competing, narratives of Africa.

I have picked out a few books by contemporary African writers here, books that I myself enjoyed greatly, ones that I hope you will enjoy too. In the age of e-commerce and e-books, procuring the books will also not be too difficult. In any case, part of the pleasure of a dogged reader is in hunting down a book.

But I do owe you an explanation about this selection, and the very idea of “African” literature. ‘Is that even a category?’ you ask, and rightly. For a continent as massive as this, and home to so many nations (and before nations, there were 10 times as many tribal identities), is it not politically incorrect to club it all under one umbrella?

Well, in my opinion, it’s okay to work with the idea of African literature, and here’s why. The nuanced appreciation of the idea of separateness as a sociological marker is, without argument, a noble thing. That said, sociological wars can only be truly won when economic wars are won, and the real challenges facing African nations are those in economics. And in that sense, the idea of Africa as united rather than divided is an empowering, if somewhat radical, tool. It is in this optimistic pan-Africanist vein that I have made my selection of books.

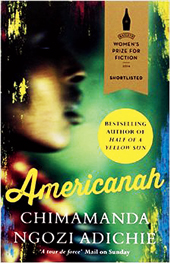

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Often considered the most powerful voice in contemporary Anglophone writing from Africa, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie grew up in the university town of Nsukka in Nigeria, in fact, living, for many years, in a house where legendary African writer Chinua Achebe had once lived. Her parents were both academics associated with the university. At the age of 19, she abandoned the study of medicine and moved to the United States as a student, and many of her experiences in the US are shared by Ifemelu, the protagonist of her third novel, Americanah.

Leaving behind her sweetheart of many years, Obinze, in Nigeria, Ifemelu comes to the US and for the first time in her life feels “black”. As a coloured immigrant, she observes the American dream from certain unique angles, and after several years and several loves (though Obinze always remains uppermost on her mind), she starts a blog on race that becomes extremely popular: “Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black”.

In a clever device, Ngozi Adichie uses the blog to offer a fresh and urgent commentary on race relations in America. From language to hair care (Ifemelu refuses to straighten her hair and refers to a website called HappilyKinkyNappy.com to figure out the best ways to deal with her hair), the blog often makes the personal, political and the political, personal. The blog superbly complements the narrative arcs that traverse the lives of Ifemelu and Obinze, over the years, moving from different cities in the US and the UK, to the changing globalising landscapes of contemporary Lagos.

One Day I Will Write About This Place by Binyavanga Wainaina

“Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title. Subtitles may include the words ‘Zanzibar’, ‘Masai’, ‘Zulu’, ‘Zambezi’, ‘Congo’, ‘Nile’, ‘Big’, ‘Sky’, ‘Shadow’, ‘Drum’, ‘Sun’ or ‘Bygone’. Also useful are words such as ‘Guerrillas’, ‘Timeless’, ‘Primordial’ and ‘Tribal’. Note that ‘People’ means Africans who are not black, while ‘The People’ means black Africans.” (From How to Write About Africa by Binyavanga Wainaina, Published in Granta ’92.)

Nominated one of 100 most influential people by Time magazine in 2014, Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina, who is also the founding editor of the literary magazine Kwani? (So what?), is one of the coolest intellectuals today. His powerful memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place, about his childhood and youth — Kenya where he grew up, South Africa where he went to college, and later on his travels through other parts of east Africa, is a must-read for its prose, its felicity, and finally, to an Indian reader, the deep sense of kinship it evokes.

A few months back, Wainaina’s short sketch I am a homosexual, Mum, purportedly a lost chapter from his autobiography, was published in

The New York Times. His coming out at a time when a new spate of anti-gay laws were passed in Kenya heralded the beginning of a reopening of the debate on this in his country. Wainaina is also a great believer in the radical powers of the Internet to subvert the “mainstream” and is very active — and educative — on Twitter (@BinyavangaW).

Arctic Summer by Damon Galgut

The subject of the brilliant South African author and playwright Damon Galgut’s most recent novel Arctic Summer is the haunting — and somewhat haunted — British writer E.M. Forster, and the years of his life from 1906 when he first met Syed Ross Masood, his Indian friend and former student, the unrequited love for whom drew him to India the first time, and the publication of his most successful book,

A Passage to India, in 1924, which had remained in incubation for about 14 years.

Forster’s homosexuality (“minorism” as it was called pejoratively in that time) had caused him great anxiety in repressive Britain, and it was his travels, in India, then Egypt during the Great War, and then in India again, that freed him somewhat from the claustrophobia of his cloistered English life, as a companion to his mother and sometimes to his aunts.

Galgut’s moving novel is a remarkable tribute to Forster and perhaps, even more so, to India, where Galgut has also spent a lot of time.

There is no doubt in my mind that Damon Galgut has emerged as one of the most original literary voices of our times. Arctic Summer (the title is borrowed from Forster’s own unfinished novel) is particularly a must-read for anyone who has read — and critiqued — A Passage to India.

Lyrics Alley by Leila Aboulela

The cover of Lyrics Alley — two women in abaya in a courtyard — underscores the old “ethnic” stereotyping of African and Asian fiction that invariably occurs in the publishing process. The cover notwithstanding, the women in Lyrics Alley are no way caricatures or stereotypes. Nor are the men, for that matter.

Set in the early 1950s in north Africa — from the busy streets of Khartoum to the cosmopolitan urbanity of Cairo — the novel traces several years in the life of a Sudanese family headquartered in Omdurman.

Mahmoud Abuzeid is the patriarch, a business tycoon who deals in cotton, and has found a unique way to balance tradition and modernity. His first wife, the conservative Sudanese Hajjah Waheeba, mother of two sons, is a traditional woman who runs a traditional kitchen and handles the estates with dexterity. She is a firm believer in the old ways (read: female circumcision).

His second wife, the fashionable Cairene Nabilah, is almost an antithesis to Hajjah. She lives in her European-style apartment in the family compound, serves fancy food and dreams of Cairo obsessively. Within the larger contours of the family, the tragic love story of Nur, the younger son of Mahmoud Abuzeid, and Soraya, his beautiful niece, is enacted. In the distant backdrop is the very real rumble of change: the end of the British empire.

A delicious book by an accomplished novelist who was herself born in Cairo but grew up in Khartoum and was the winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing, Lyrics Alley is perfect reading for a weekend of escaping the hot May sun.

Baking Cakes in Kigali by Gaile Parkin

As pudding to this five-course meal, I could not resist including this charming book by Gaile Parkin. Though Parkin holds a British passport, she was born in Zambia and has lived in different African countries for most of her life. Set in Rwanda that is being reconstructed after war and where dollars are raining, particularly for foreigners, the novel revolves around Angel Tungaraza, a native of Tanzania and a famous baker, who lives in Kigali with her husband Pius, a consultant to the university, and her five grandchildren who have all come to live with her after her son and her daughter passed away in quick succession.

Filled with delicious descriptions of cakes that Angel bakes, with great skill and imagination, and deeply moving, often-true, stories from people’s lives (from AIDS to missing children, female circumcision to mindless tribal violence and the politics of aid-giving and intelligence games, there is no issue that Angel does not encounter in her drawing room at home), delivered with sparkling humour and humanity, this book will leave you satisfied and oddly hungry. After all, the healing powers of baking are well-documented!

Devapriya Roy is the author of The Vague Woman’s Handbook and other titles, including the just-published

The Heat and Dust Project, co-written with husband Saurav Jha. You can tweet her at @DevapriyaRoy