Continuing the conversation with Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, whose Film Heritage Foundation is pioneering the cause of restoring ‘lost’ classics of Indian cinema, we spotlight the efforts to restore two G. Aravindan classics – Kummatty and Thampu.

Can you take us through the various stages of restoration?

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur: The first step in a restoration project is to identify the film we would like to restore. As a Foundation, our approach to selecting films for restoration is to choose hidden gems, films in danger of being forgotten or lost. In the case of Aravindan’s films there was a sense of urgency as most of the original camera negatives of his films do not survive and the material that remains is not in the best condition. If we did not take up the restoration of his films, there was a chance that no one would be able to see the work of an artiste as it was meant to be seen and the world would have to make do with poor-quality copies.

Then one has to understand who holds the copyright as you need to get their permission to restore and close the terms and conditions of the agreement with them. Once the permission is in place, we put out a call to the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) around the globe to identify the available material. The best source material would obviously be the original camera negative if that is in good condition. If not, one uses dupe (duplicate) negatives, fine grain positives, prints, etc. One has to study the condition of the film elements, if they are complete, and do a film comparison exercise to determine the best elements to put through the scanner. But before the film can be put through a scanner, it usually needs to be cleaned and repaired as films could have tears or broken sprockets that need to be fixed. For the scanning, one has to decide whether the film needs a wet gate scan and also the parameters have to be set before the scanning begins. Once the film has been scanned, the next steps are the digital clean-up, colour correction and sound restoration before finally the mastering of the film depending on the output required, which could be DCPs for theatrical screenings, MOV files for access and LTO tapes for long-term preservation.

RESTORATION OF KUMMATTY

The Preservation

Once we had the official go-ahead, we put out a call through the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) to member archives and institutions all around the world searching for the best available source elements that we could use for the restoration. For a film restoration, the best element is the original camera negative, but sadly, as I had feared, none of the original camera negatives of Aravindan’s films survived – they had all melted and nothing could be salvaged from the liquefied celluloid. The loss of the original camera negative was a big blow as prints can never give you the same latitude as a negative.

We received responses from the Library of Congress in the USA and the Fukuoka Archive in Japan that they had prints, but they were not in very good condition and in the case of the prints in Japan, Japanese subtitles had been embedded into the film. I remembered that in a conversation with P.K. Nair (the former director of the National Film Archive of India), he had mentioned that the NFAI collection had prints of Kummatty including an unsubtitled one. I checked with the Kiran Dhiwar, Film Preservation Officer at NFAI, who confirmed that the archive had two prints of the film. On the producers’ request, the NFAI made arrangements for me to check the prints at the archive. I travelled to Pune with Pravin Singh Sisodia, our foundation’s film conservator. The prints were not in great condition but they were shipped to the L’Immagine Ritrovata lab in Bologna. Had it not been for the NFAI having preserved these prints over the years, the restoration would not have been possible. The fact is without preservation, there can be no restoration and India’s record of preservation is abysmal.

The Colour

The restoration itself was very challenging. Cecilia Cenciarelli of Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna sent us the lab inspection report which was daunting. Both the prints had a lot of wear and tear and were very dirty and deeply scratched. One of the prints presented a consistent vertical green line on the right-hand side of the image, which required painstaking frame-by-frame manual work to be removed. The colour of the positive was decayed and the film’s natural environment, an essential character of the film, had completely lost its rich palette of skies, grasslands and foliage, and become all magenta. This presented a real challenge for Diego, the technician who had to spend days working on the colour grading to get it right. Even with highly-skilled technicians working with the latest digital technology, the lab said that there were still sections of the film where the details could not be recovered and were lost due to the poor condition of the print and consequently the scanned image.

The Original Vision

We were very fortunate that Ramu Aravindan had photographs of the shooting location which served as a crucial reference for the colourist. Additionally, we were very grateful that celebrated cinematographer and film-maker Shaji N. Karun, who had shot so many of Aravindan’s films and worked closely with him, made himself available for several long Zoom calls along with myself and Ramu Aravindan and the colourist at the lab in Bologna to ensure that Aravindan’s original vision was honoured to the best possible standard. Normally this would have been done physically sitting with the colourist at the lab. Doing this remotely over Zoom calls and checking file transfers was a long and arduous process.

The Sound

Being a musician, Aravindan was very particular about the seamless blending of the music and sound design of his films. Unfortunately, in the case of Kummatty we were hampered once again by the fact that we did not have the original sound negative and were working with the sound from the print, which was far from ideal. Ramu Aravindan helped us to source his father’s quarter-inch tapes and we digitised about 15 of them in the hope of finding better source material, but there was none. As a result, the sound engineers at the lab had to spend many hours cleaning up and remastering the sound.

The Screening: Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna

But the result more than made up for all the struggles and pitfalls we had faced. The restored film was screened at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna on July 25, 2021. I was so sad that I could not be there to see it for myself on the big screen, but friends who watched it were blown away by the imagery, colour and sheer poetry of the film, which shone like a jewel on the big screen. I wish Aravindan could have been there to see his film get a new life.

RESTORATION OF THAMPU

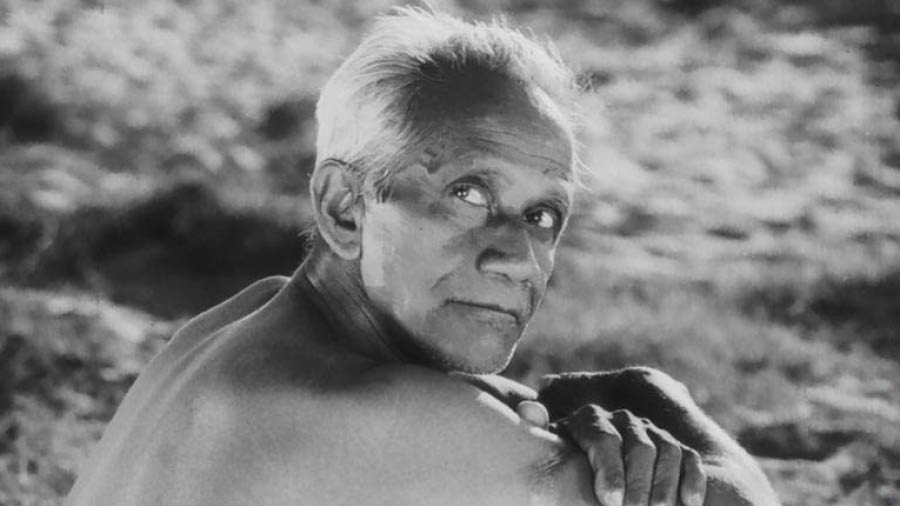

A still from Thampu. IMDb

The Dupe Negative

The restoration of Thampu was very challenging too. We were aware that the NFAI had film elements of Thampu in its collection, but we needed to ascertain exactly what they had and assess the condition of the material. Film Heritage Foundation, as a member of the International Federation of Film Archives, also put out a call to all the 171 member institutions around the world to check if they had film elements of Thampu in the hope that we might still discover good condition prints or dupe (duplicate) negatives in some part of the world. However, the only response we got was from the Fukuoka Archive in Japan that had prints with Japanese subtitles burned into the print, which made the material unusable for a restoration.

We then got in touch with the NFAI and our film conservators travelled to Pune to do a condition assessment of the Thampu film elements in their collection. While there was no original camera negative, we found that we could use a dupe negative struck from a 35mm print that was at the NFAI. A second 35mm print could be used for comparison. As per the condition assessment report prepared by our conservators, there were tears and broken sprockets in the films which were repaired by our conservators. The other challenge was that as the dupe negative was struck from a print, it did not have as much latitude as an original camera negative would have had. We first did a test scan of both the print and the dupe negative. Having worked with both Prasad Studio in Chennai and L’Immagine Ritrovata, Bologna, we decided that we would split the restoration process between the two labs and requested Davide Pozzi, Director of L’Immagine Ritrovata, one of the best restoration labs in the world, to supervise the restoration.

The Scanning

We spoke to Saiprasad Akkeneni of the Prasad Corporation Pvt. Ltd. in Chennai, who agreed to partner with us on the restoration by doing the scanning and digital clean-up of the film at their facilities in Chennai. As a good-quality scan is the basis of a world-class restoration, Davide Pozzi set the parameters of the scan and agreed to oversee the process. The scanning of the picture and sound and the hours of manual work that went into the digital clean-up of the scratches and tears and the image stabilisation was done at Prasad Studios in Chennai. The restoration workflow was a process that needed constant coordination between myself in Mumbai, the Prasad technicians in Chennai and the lab in Bologna.

The Grading

Thampu was shot in black-and-white by Shaji N. Karun on Indu Stock, an Indian brand of film stock that was manufactured in Ooty. The source material was in poor condition so the scanned film had thick black lines, very grainy images and required image stabilisation. In the print we worked on, the outdoor scenes were full of high-contrast images – the blacks were very black and the whites were very white, with no mid-tones and no details of shadows. We didn’t want the film to look absolutely clean; we wanted to match the beauty of the original imagery and to retain some of the grain so the film still had the feel of celluloid.

Both Ramu Aravindan, photographer, graphic designer and the son of Aravindan and the cinematographer Shaji N. Karun, who shot the film, besides myself gave constant inputs and feedback on the grade. Files would be emailed from Bologna and every time we would get a bunch of files I would go to see them in a studio to assess the grading and to see how the film looked on a big screen. Another huge challenge was the sound which was very poor quality as it was taken from the print. A lot of work had to be done in Bologna on the sound restoration, which took months and was so important as sound design is such a key element of Aravindan’s films.

The Screening: Cannes Classic

Thampu is such a beautiful film that I knew if we could restore it to world-class standards, it would get us to Cannes. And I was proved right when our restoration was selected for a red- carpet world premiere at the Cannes Classic selection. It was an incredibly proud moment when we were told that the film was the discovery of the year.

The process of restoring a film must be expensive – where do you source funds from? Is the government backing the efforts?

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur: Funding for film preservation and restoration is a challenge. In the case of the restoration of Thampu and Kummatty, we have been fortunate to have partners like Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation, Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna, L’Immagine Ritrovata and Prasad Studios (the latter in the case of Thampu), and we have put in our own resources and funds as well to restore these films. We are hoping that the success of these restorations will draw in more sponsors that will fund our next restoration projects like Aribam Syam Sharma’s Ishanou and Nirad Mohapatra’s Maya Miriga.