Motion pictures are strange things. They capture and keep the impression of a person as he or she was 20, 30, 40, even 70 years ago.

That allows generations of women and men to rave about the same matinee idol. I remember a friend waxing lyrical over the good-looks quotient of Clint Eastwood in the classic, Where Eagles Dare, shot before either of us was born. This was a good many years ago. And then her mother joined in the conversation and bashfully acknowledged her, er..., fondness for Eastwood.

Of course, fictional characters have always had fans spanning generations, but actors are real people — which makes this entire business of timeless appeal a bit odd when put under the microscope, but there it is. That is why when I acknowledge that I cannot get over Soumitra Chatterjee — the bad boy from Teen Bhubaner Parey teasing Tanuja with Ke tumi, nandini... — I do so with trepidation. But the truth is the truth, and truth is that Soumitra has been shaping my idea of the perfect Bengali man since before I was even a thought in my mother’s mind.

In Apur Sansar, he is romantic and injured — having lost his wife to childbirth, he stays away from his young son who for the longest time is just a painful reminder of all that he loved and lost. In Samapti, he is romantic, reserved and gallant. His Amulya falls in love with a tomboy, marries her against her wishes, and then waits patiently for Mrinmoyee to return his affection. In Devi, his is the civilising presence in an off-kilter world, he is the bhadralok in shining armour. In Teen Bhubaner Parey, he is romantic and rogue, reluctant to be rescued by his knightess in shining armour. In Abhijan, he is brooding, smouldering, a man-igma in love with his Chrysler.

Of course, he played all those other characters too. The charming but feckless Amal in Charulata, the weak-willed and jealous Sekhar in Parineeta, the fiery but inherently selfish Sandip in Ghare Baire, Amitabha in Kapurush who is too cowardly to marry his girlfriend but has no qualms about asking a married woman to run away with him. Characters you are far more liable to come across in real life, characters you would be well served to identify and avoid, characters that Soumitra made his own.

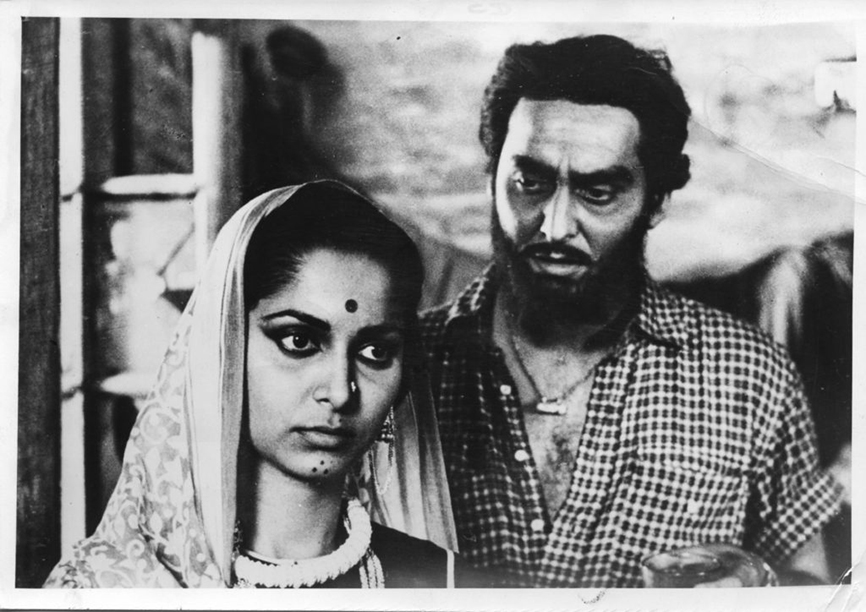

With Wahida Rehman in Abhijan File picture

But the role in which I like him best is... none of these.

There was a time in my life when I was fascinated by Anthony Hope’s novel The Prisoner of Zenda — the duty-bound princess, the king, the lookalike. When I learnt that there was not only a Bengali adaptation of the work, Saradindu Bandopadhyay’s Jhinder Bondi, but also a film by the same name, I was intrigued.

When I finally watched Jhinder Bondi on TV, I was blown away. Not by the story I knew so well or the princess I so admired, not even by matinee idol Uttam Kumar who played the double role of king and commoner, but by the villain’s villain, Mayurbahon, played by Soumitra.

The sharp actor imbued the character with temper, swagger and wicked charm such that Mayurbahon overshadowed the king’s brother, the Villain No. 1 — I cannot even remember the character’s name. And when he galloped up to the camera on a white steed in bandhgala and turban, I forgot there was an actual king somewhere in that frame. If others could see that scene through my eyes, the Uttam-Soumitra debate would end in a second. Why? Because Kumar is a version of himself in that movie, while Soumitra is Mayurbahon — a prince, my prince, on the wrong side of the law.

If I have mostly incantated the roles Soumitra played in Ray’s films, it is because my film buff parents raised me on that diet. In fact, the first movie I watched in a cinema hall, my feet dangling from the seat, was Ray’s Hirak Rajar Deshe. Soumitra played the idealistic schoolteacher, tutoring his students in rebellion against the tyrant king. While I delighted in the film, I am not sure what the five-year-old me made of Soumitra’s role in it.

The character I wasn’t too young to appreciate was Soumitra’s rendition of the sleuth Feluda in Sonar Kella. And I dare say, I will never be too old not to appreciate it.

Feluda, aka Pradosh Mitter, is a character created by Ray. He is a tall, lean man, wields the pistol with ease, and with still greater ease his agile mind. Much like his creator, he has a cigarette dangling from his lips and yet, if you look at Ray’s illustrations, the master sleuth seems to have been modelled on Soumitra and not Ray himself.

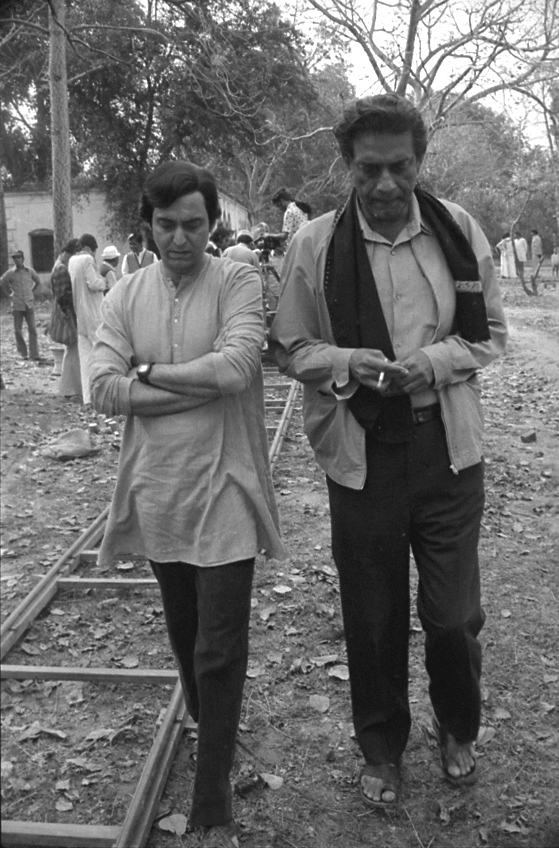

With Satyajit Ray Courtesy, Sandip Ray

By the time Soumitra played Feluda in his second film (Joy Baba Felunath), he was already too old for the character. Yet to most Bengalis, Soumitra is Feluda and all those actors who have come after him are just placeholders. Feluda is a character a whole generation has grown up with and idolises. Feluda is why the Bengali woman’s ideal man is sharp and erudite, brave and plainspoken. Feluda is also why so many of us love our cigarettes, to smoke or to passive smoke.

Of course, when my mother hoped to marry a tall, handsome man who smoked, it was Soumitra she was modelling her future bridegroom on, not Feluda. One of my aunt’s favourite stories to tell is about the time she and my mother suddenly met Soumitra at a friend’s house and my loquacious mother, who can speak seven languages and carry on a conversation all by herself, could not think of a single thing to say to the man she was a fan of. Unfortunately, my grandfather never asked her what sort of a man she would like to marry and so she ended up marrying my short, bald, never-smoked-in-his-life father.

I too have a met-Soumitra story. In the beginning of this century, I lived in a matchbox place close to Feluda’s two-storey house in south Calcutta. So close in fact that I had to pass his house on my way to the grocery store. One day, when the boyfriend and I were returning with our arms full of groceries, we noticed the star’s Fiat parked outside.

“Puluda something,” said the boyfriend-eventually-turned-husband invoking the dak naam of the film star in a loud voice. And what do you know, the car door opened and the man himself stepped out in slow motion. I distinctly remember the paralysing shame I felt, trapped under the gaze of the actor I adored. He must have heard us, but he took our overt familiarity in his stride and gifted us a smile, one of an indulgent uncle.

Nearly all stars look the best against a dark firmament, it is only a rare one and a big one that can twinkle on the ground, in broad daylight.