Watching Mujib: The Making of a Nation, I was reminded of Dhritiman Chatterji’s iconic interview sequence in Satyajit Ray’s Pratidwandi.

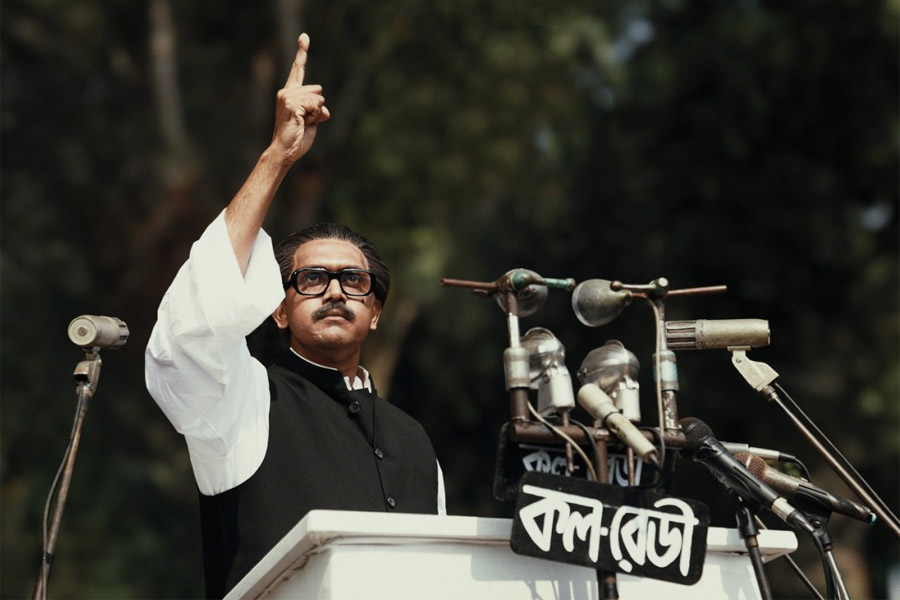

Ray’s film released in October 1970, barely a few months before the turmoil in East Pakistan arising out of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s speech on March 7, 1971 calling upon his countrymen in the east ‘to turn every house into a fortress’ [because] ‘this time the struggle is for our liberation! This time the struggle is for our independence’. It was just short of a year of the creation of Bangladesh in December 1971.

Between March 1971 and December 1971, as Pakistani armed forces unleashed genocide on its eastern wing and millions of Bengali refugees fled into neighbouring India, the world witnessed the formation of the guerrilla resistance group, the Mukti Bahini, and one of the most heroic struggles of the common man against the might of a military force stronger and better equipped than they were.

If Pratidwandi’s Siddhartha were asked the same question after the liberation of Bangladesh – namely, the most significant world event in the last 10 years – would his reply have been any different? Would he have said ‘Bangladesh’? The ‘plain human courage shown by the people of Vietnam’ that Siddhartha mentions is applicable as much to the people of Bangladesh. Particularly for a Bengali, long derided for his puny physical stature and lack of martial acumen (there’s an interesting speech in the film where Mujib refers to this and warns his countrymen in the west that the rice-eating Bengali does have the stomach for a fight), it does not get bigger than this. Also, the political, social and economic repercussions of the Mukti Bahini’s struggles and Mujib’s crowning moment would have appealed to Siddhartha’s intellect.

Watching Mujib: The Making of a Nation, however, I was also aware that such speculation was academic, because nothing about Shyam Benegal’s film even scratches the surface of the complexities of the formation of Bangladesh and Mujib’s role in it. As far as biopics go, this is as bland and hollow an enterprise as the recent Bengali release Bagha Jatin, with a strictly by-the-numbers Wikipedia feel to it.

There was a time when Benegal could imbue a biopic like Bhumika with cinematic flourishes that are still emulated. Or even in his later biopics on Bose and Gandhi, flawed, often didactic, but still made watchable through the sheer force of his filmmaking. There was a time when Shama Zaidi could render films like Garm Hava and Umrao Jaan veritable exercises in the art of screenplay writing. Mujib (scripted by Shama Zaidi and Atul Tiwari who also wrote Benegal’s film on Bose) is workmanlike at best and plain boring, even juvenile in parts.

Yes, a lot of the lack of frisson in the narrative has to do with the project being a government-sponsored one. In a film culture that has never quite done justice to biopics, retaining any objectivity in a government-backed project is a pipedream. However, what galls about Mujib is how the narrative and the filmmaking never look like even attempting to rise above the limitations imposed by the need for government sanction. Surely, with the budget at its disposal and all the amenities at their beck and call, the filmmakers could have crafted the general uprising, the guerrilla warfare sequences, the killing of civilians, and the final shootout more cinematically. For a film made in 2023, some of the action reminded me of our films in the 1970s and ’80s where both the shooter holding an automatic gun and the person shot shake as if in the throes of a bout of malaria.

The decision to frame the narrative in a voiceover by Mujib’s wife robs the film of all nuances, making it a simplistic and mechanical recounting of an extraordinary life – the first meeting between them, Mujib’s initiation into the politics of pre-partition Bengal, the rise of communalism in the days leading up to the partition in 1947, the language agitation, and so on and so forth. There are interesting throwaways about Mujib’s relationship with Fazlul Haq and more importantly Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. As also his approach towards Gandhi and his teaching which he recalls in the days of his struggle for independence and incarceration at the hands of the Pakistani army. There are also the nuances of cultural oneness trumping religion that was at the heart of the formation of Bangladesh.

But all these are just skimmed over. Particularly abysmal is the total lack of emotional heft to one of the most dramatic of events that shaped Bangladesh – the language agitation of 1952 and the killing of students on February 21, 1952, celebrated as Martyrs Day in Bangladesh and now also as International Mother Language Day. It’s a sequence lacking any power and momentum, and more or less sums up the lacklustre nature of the overall narrative.

Of course, in a government-sanctioned project there is no way one can expect an articulation of the events after 1971, and how a champion of freedom and human rights like Mujib ended up creating one-party rule, falling back on familiar tropes of ‘left ultras, foreign powers’ out to destabilise the nation, and the increasingly prickly relationship with India after the bonhomie of the year leading to the independence of Bangladesh.

Maybe this would have been a better film instead of an all-encompassing biography, if it focused on a certain period of the life of its protagonist. It is particularly galling that we have little insight about the man after 178 tedious minutes. Like many great political leaders, Mujib was a complex man. Shyam Benegal’s film sadly makes him one-dimensional, giving the viewer little to take away about the man behind the leader, barring an immensely lovable family man. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman deserved a better film. As does the era the film covers. The audience does too.

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer