Sholay, whose every mood and moment remains etched in the minds of moviegoers across generations, clocks 45 years today. Over a long chat with its director Ramesh Sippy, The Telegraph relived the iconic 1975 film, a larger-than-life cinematic experience that starred some of the biggest names of the time and was a nod to many a classic Western and yet embodied every aspect of the quintessential Bollywood movie.

Forty five years is a huge milestone. Does it feel like yesterday or does it feel like a lifetime?

Both! It seems like yesterday, but I know it’s a lifetime (laughs).

In a film this iconic spanning generations, what aspects of making Sholay still remain fresh in your memory?

The beginning to the end, every character, every mood and every moment. The moment with Mausi (Leela Mishra) is as memorable as Dharamji (Dharmendra) on the tank. It was a difficult film to make, it took a lot of time and effort... but it was an experience we all cherished. Not just the cast, but all the technicians — whether it was Pancham (RD Burman, who scored the music), Rafi saab (Mohd Rafi) and Salim-Javed (who co-wrote the film), of course — we all rallied together to make Sholay. The stereophonic sound was one-of-its-kind, recorded at the Twickenham Studios in London. The colour, the 70mm prints.... There was so much input into the film and from so many different quarters. We built a village (at Ramanagaram, a town near Bangalore) and had so many people living there for months. It was an unbelievable and a mammoth task and we did it for a year-and-a-half.

I went from moment to moment and tackled each thing as it came. Of course, there was planning... but if I had thought of the whole in advance, in terms of each and every thing that I would do, I don’t think I would have been able to do it. I would have constantly thought, ‘Oh, how can I do this?! It’s going to be impossible!’: Ramesh Sippy Sourced by the Telegraph

Sholay was made on a larger-than-life scale at a time when you didn’t have any of today’s technology and logistics at your disposal. Did you, at any point of time, feel you had taken on too much? You made the film when you were only 29...

No. In fact, if I had decided to make Sholay today, it would have been even more difficult because everything would have to be planned in advance, otherwise the studios of today wouldn’t have parted with the money! (Laughs) I went from moment to moment and tackled each thing as it came. Of course, there was planning... but if I had thought of the whole in advance, in terms of each and every thing that I would do, I don’t think I would have been able to do it. I would have constantly thought, ‘Oh, how can I do this?! It’s going to be impossible!’ But because I overcame problems as they came, it was possible to get through with it. Something about that way of working worked for the film.

We had budgeted the film for a crore and it went on to cost (Rs) 3 crore. If I had thought of the pressure of three crore at that time, I would have possibly not been able to go ahead. If someone had told me that this money might not be recovered, then I would have had to think and say, ‘Well, then let’s not make it’. Or I may have had to say, ‘Okay, we won’t do this and we won’t do that’. Thank God, that didn’t happen!

When you were making it, did you have a gut feeling that it would become what it became? Or does one mostly stand to lose perspective when one is in the process of making a piece of art?

If you think that what you are making is out of this world and is a phenomenon, then you are a mad man! (Laughs) Most importantly, you won’t be able to do it. A phenomena is what happens... you can never plan it. You do your best, you do all the work that is in your hands... your craft and your imagination comes into play. But you can’t really think, ‘Oh, this is going to be remembered for 50 years and beyond’. Who would have thought that every line of Sholay would become iconic and would be repeated close to 50 years down the line? There have been so many tributes, so many spin-offs, so many takes on Sholay... who could have thought of that? We were just focused on making a good film. Technology has changed, platforms of entertainment have changed, but Sholay endures.

It’s been widely documented that Sholay was declared a flop in the first weekend...

That’s documented for sure, but it’s a misconception. It’s the trade pundits who slammed it and predicted doom, not the audience. It’s not like today where you book a ticket online and go into the theatre. People had to line up for hours and hours outside the movie theatre to get a ticket. In the opening weekend, there definitely was a crowd and it was actually the blackmarketeers who were lining up people, getting the tickets from the counter and outselling them! (Laughs)

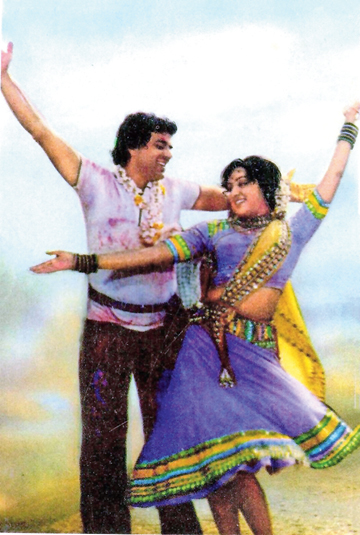

Dharmendra with Hema Malini, who played Basanti Still from the film

What I know is that the film released on Friday and by Saturday, the trade pundits completely slammed it. All of them... there was no exception! (Laughs) That brought on a pall of gloom over the whole unit and we honestly started doubting ourselves for a moment. ‘If everyone is saying it, have we got it wrong?’ is what we kept wondering.

When I went into the theatre to watch the film, there was complete silence. Something that one could interpret in two ways.

They were not reacting, but we later found out that it happened because they were stunned! (Laughs) They had not seen anything like this before, and that is why they were quiet.

On the fifth or seventh day after release, a theatre owner called me to pay a visit. When I went there, he pointed out the stalls where soda and popcorn were being sold, and they were empty. I thought he would give me yet another dose on the fact that the film was not working. But what he said is, ‘No one wants to leave the movie and come here to buy refreshments... they don’t want to leave their seats!’ (Laughs) So that was the first person who actually gave me the hint that Sholay was on its way to becoming a phenomenal hit.

By the second or the third week, we had started getting in a huge amount of repeat audiences. So it was just not that they were coming... they were coming, and coming back! They were repeating the lines and enacting the scenes inside the theatre. And then the critics started slowly admitting that it was the biggest hit (smiles). Or as they say, they started eating their words! (Laughs).

It’s also the stuff of legend that the negative reviews propelled the team to want to change the film’s ending...

There are two aspects to that. One was a censor (board) problem. The original ending that I had shot but didn’t make its way into the film was one in which Thakur (Sanjeev Kumar) kills Gabbar Singh (Amjad Khan)... but the censors didn’t allow that. It was the time of the Emergency... 1975 was the year of the Emergency... and there was no way to go to courts or battle the censor board. It would have been futile. Their argument was that, ‘How can a policeman do this? He can’t take the law into his own hands’. It’s another thing that Thakur didn’t have any hands! (Laughs) I had to accept that and we reshot the ending where Thakur is stopped from launching into that final thrust on Gabbar, and the police comes in and takes Gabbar away. So we had to follow the template of many films of that time... you know the ones where the policemen would come in after all the action was over!

The other thing was the story going around about Jai’s (played by Amitabh Bachchan) death. Yes, because of this initial pall of gloom and the self-doubt that was sown, we discussed things and we decided to change the ending and keep Jai alive, with Jai and Veeru (Dharmendra) fighting together. But that meant that all the sequences after that would also go to hell! (Laughs) That’s when we realised that it would become a huge task and we decided to leave it as it is. Everyone agreed that let’s stick to what we have, let’s stick to what we have believed in.... Of course, people went, ‘Ooh! Aah! Why did he have to die?!’ But then that was the whole emotion. That was the note on which Dharamji (Veeru) gets up and says, ‘Gabbar, main aa raha hoon!’ There’s something called story and screenplay and leading from one scene to another and we didn’t want to play with it.

In a film that has so many iconic scenes, one sequence that’s always stood out for me, though acutely tragic, is the one in which Gabbar kills Thakur’s family. I believe there’s a story behind filming that scene, a nod of sorts to the massacre scene in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West. Can you talk us through that?

We shot that sequence for a couple of days. And then the clouds came on. We waited a few days, but they didn’t go away. I was fidgety and I kept walking around and suddenly it struck me, ‘What if we shoot it in this weather?’ I felt that the weather would give the scene a kind of doomsday feeling, a feeling that something’s in the air. I asked my cameraman (Dwarka Divecha), ‘What if we shoot it like this?’ He was like, ‘Ya, but what if the sun comes out tomorrow?!’ But by the end of the day, the whole thing began to grow in my head... that this is the way I want it. I wanted this feeling of dread, I wanted the wind to pick up the leaves and signify the building up of the fury inside the man (Thakur) and that’s when he sits on the horse and gallops into Gabbar’s den. Once that picture emerged, I couldn’t get it out of my head. We started to shoot... and of course, the sun had to come out after two days! (Laughs) But then I decided to wait for the clouds. When there were close-ups, we would cover the top and shoot and when we had a cloudy day, we would take the long shots. It took 21 days to shoot that one sequence.

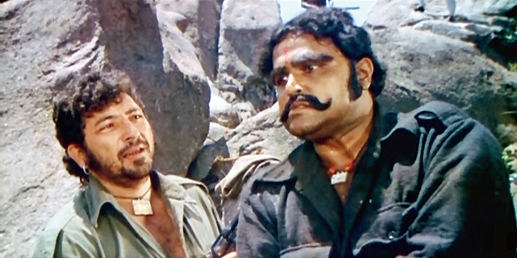

Amjad Khan as Gabbar Singh, with Viju Khote who played Kaalia Still from the film

So movie-making is sometimes about planning, sometimes about on-the-spot decisions and sometimes about going with the change. I took that chance, and my father (producer G.P. Sippy) was also a very large-hearted man. However much it went over budget, he didn’t say a word. I had that backing from him, and all the artistes and technicians stood by me... they put their hearts and souls into it.

Forty five years down the line, why do you think Sholay’s appeal endures?

I think because even if it was made for the theatre, people enjoy it today on any kind of screen. If you have a good screen and a good sound system, Sholay still feels like a theatre-going experience. You are immediately transported into that world. Also, Sholay is much more than just one line or one moment. ‘Kitne aadmi thhe?’ is as frequently used in everyday language as ‘Itna sannata kyun hain?’ The lines are so fabulous, but Sholay endures because it’s the impact of the film as a whole.

We had taken out a record of the dialogues after release. One fed into the another, in the sense that audiences saw the film, they bought that soundtrack, they would play it at home and reimagine the whole film and then say, ‘I want to see it again’. And when they came back from the film, they wanted to hear the dialogues again!’ (Laughs)

What does the younger generation, having watched Sholay much later, tell you about the film?

They all say they love it, but it surely cannot have the same impact as it did on the generation that first watched it in the theatre. Their parents say that when they sit down to watch it again, their children also want to watch it with them. Every generation will have its own favourites and its own heroes, so I really don’t know if Sholay is as popular with subsequent generations. But if we are talking about it 45 years later, then Sholay is still pretty much up there (smiles).

You’ve made many other iconic films like Seeta Aur Geeta, Shakti, Shaan and Saagar as well as the TV series Buniyaad. Would you consider Sholay to be the centrepiece of your legacy?

Even if I didn’t want to, it would still be! (Laughs) Sholay is a phenomenon, it’s beyond everything else. Sholay is also a story of so many things falling into place. The role of Gabbar was initially supposed to be played by Danny Denzongpa, but he was stuck in Afghanistan shooting for Feroz Khan’s Dharmatma. I had to let go of him. But today when you look back, Gabbar is Amjad and Amjad is Gabbar. Would it have had the same impact if Danny had done it? I really don’t know. But it’s almost impossible to imagine it in any other way.

We do, sometimes.When we meet, we talk about the film and also about other things. There’s always a feeling of nostalgia and it’s great to meet with the people who made Sholay what it is and relive some moments, and the good feeling that we were part of it. The pandemic is upon us right now, but we will try and have a 50-year celebration. Let’s see.

What does Sholay mean to you? Tell t2@abp.in