How far will you be willing to go to make your life better? To what extent can you push through when it comes to realising your ambition through your child? What happens when that ambition is born not out of a desire to ace the rat race but to cock a snook at decades of systematic marginalisation?

At a time when the ugliness of privilege vs non-privilege is palpable more than ever in the country, Serious Men, dropping on Netflix today, is a sharp and incisive look at caste and social construct through the eyes of a Dalit man. A man who is both more brainy and ballsy than the people whose egos he needs to massage on a daily basis, but one who is unable to rise above his lot in life because of what and where he was born into.

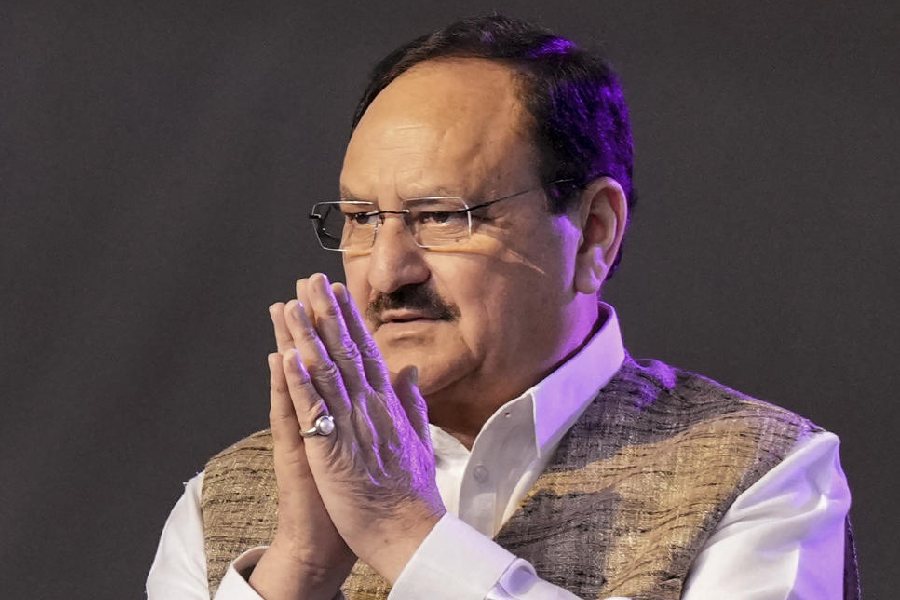

Nawazuddin Siddiqui is Ayyan Mani. We say that because no one else could perhaps have been Ayyan Mani. You see it in the eyes. You spy derision when the Dalit man in him sees the ‘serious men’ (a term Ayyan spits out often) at the scientific research institute where he works, including his Brahmin boss Acharya (Nassar), pulling off one public scam after another, including one where the latter claims he can prove the existence of microbes in the stratosphere, all the while conning the state for funds. You see tenderness and hope in those same eyes when Ayyan speaks to his wife Oja (Indira Tiwari) and outlines his ambition in life. “It takes four generations for someone to do nothing at all,” he tells Oja, while lounging by the side of a swimming pool at a five-star hotel that he’s used his street-smart slicks to gain entry into. Ayyan’s ambitions for his knee-high son Adi (Aakshath Das) are simple: he wants him to rise to become a ‘4G’ urban elite (he describes himself as ‘2G’), and perhaps one day go on to uncover the story behind some serious stuff, like the significance of dotted condoms.

It’s this consistent strain of humour in Serious Men, based on Manu Joseph’s 2010 novel of the same name and adapted into this film by Sudhir Mishra, that makes it a bold and biting satire that teases a smile out of you as often as it makes you sit back and think. Ayyan’s intent may be simple but his road to get there isn’t. Tired with living in a cramped one-room tenement in a Mumbai chawl, Ayyan hits upon the idea of projecting Adi as a child prodigy, making the young boy mug up and spit out complex mathematical equations and even more mindboggling scientific theories.

That provides Mishra ample scope to set up one engaging moment after another, which includes Adi, tutored by Ayyan, making the world sit up and take notice of his smarts. It brings the news channels to Ayyan’s door, as also a wily politician (Sanjay Narvekar) who wants to play the Dalit card through Adi in the upcoming elections, while the man’s daughter (Shweta Basu Prasad) aims to use the wunderkid to further her own ambitions with respect to a housing redevelopment project.

Mishra aces humour as well as makes an impact in that one scene where Ayyan declares himself as a ‘shudra’ in an English-medium school he wants Adi to enroll in, only to have the embarrassed man in authority shush him down.

What works for Serious Men is that it’s a collection of such winning moments (the scene in the art gallery towards the end is perhaps the most powerful in a film in recent times), all of which come together to make an almost compelling film.

Like Ayyan Mani, almost everyone is grey in the world of Serious Men. Some are driven by a sense of entitlement and some by desperation, as in the case of Ayyan, but they all manipulate the system to their advantage. So what is right and what is wrong? Who needs to be condemned and who should be let off? Serious Men lets the answers play out in between.

Serious Men is acerbic, but unlike some other films, most notably Nagraj Manjule’s Marathi gem Fandry, it lacks raw, searing, unbridled anger. Angst is good, so is acerbity. But in the times we live in, we need anger.

I liked/ didn’t like Serious Men because... Tell t2@abp.in