While Mukherjee himself felt that Satyakam stood for something unalloyed and honest in his filmmaking career (it’s a grim, somewhat depressing film whose box-office prospects were always bleak), it’s possible to make a case that his other, more accessible work has a wider ranging view of human nature. They feature protagonists with a greater sense of fun and play than the dour Satyapriya—people like the title character in Anand, or Gol Maal’s Ram Prasad, or Manju in Khubsoorat. These characters are never so hung up on a narrow view of truthfulness or “Zero Compromise” as Satyapriya is (those are qualities you see in some of the more hard-headed older people, played by Utpal Dutt or Dina Pathak, who are usually chastised by the film’s end). Satyapriya, on the other hand, lives in a black-and-white moral universe. There is little place in his world for “naatak” and “kalpana”, fantasy and imagination, which are such vital aspects of Mukherjee’s cinema. He is an outlier in a body of work that is often about deception, artifice and general tomfoolery being put to useful ends.

I loved Satyakam the first couple of times I saw it, and I still think it is wonderfully performed and structured, filmed with more care and attention to detail than most of Mukherjee’s later work, and with some scenes that still seem fresh and delightful today (note Satyapriya’s early interactions with his Dadaji, played by Ashok Kumar). And yet, I have come to feel somewhat ambivalent about it, and no longer think of it as clearly superior to the “fun” films. Happily, a movie buff doesn’t have to choose one or the other.

What goes on behind the scenes while a film is being made also has no relation to the effect that the final work might have on its audiences. The other anecdote I recall is an account by the writer and theatre director Ranjit Kapoor of how Satyakam changed his life. In 1969, Kapoor was a young man in bad company, tempted to step outside the law – “main galat raaste pe jaane wala tha,” he told me. Then he chanced to see the film and was so deeply moved by this story about an honest man struggling with the world’s harsh realities, it shifted his attitude to his circumstances.“I wept silently in the hall,” he said. “After that film, the world began to seem like a very different place – I had hit rock-bottom, but I picked myself up.”

Picking himself up meant going on to a respected career as a theatre director, and a sporadic one in cinema – the highlight being his co-writing of the script for the 1983 comedy Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro. The film has a huge cult following today, but not many of its fans realise how important Ranjit Kapoor’s contribution to it was – Kundan Shah, who directed it, once told me he considered Kapoor to be the film’s architect.

****

Kapoor’s story might seem dramatic, but that’s the sort of film Satyakam is if you get involved with it (and this may be less easy for a viewer of today, disconnected from the older, more mannered styles of filmmaking – but that’s another subject). Without getting into long-drawn plot summaries, it is about a man who refuses to compromise on his principles even if it imperils the people who depend on him; a man who says things like “Sach bolne waale ko agar dukh sahne ki himmat hai, toh dukh dene ki bhi himmat honi chahiye. (“If the truth-teller has the courage to suffer pain, he must also have the courage to give pain to others.”) In other words, not quite the most fun person at a party.

I was reminded of Satyapriya when I saw the title character in Amit Masurkar’s 2017 film Newton—an earnest government clerk who wants everything to be done as per protocol, is sent for election duty in Naxal terrain, and discovers that the world is much less ordered and more complicated than he thought it was. At the centre of both stories are two men whose inflexibility is a source of frustration to everyone around them.

But here’s a proposal: neither film is unconditionally supportive of its protagonist. Newton is more detailed and multilayered at a surface level, as our current cinema tends to be, and it offers alternate perspectives—notably that of the chief of security Aatma Singh, who understands realpolitik better than Newton does. Or the local girl who tells the well-intentioned Newton, “You live only a few hours away, but you really know nothing about us.”

Satyakam, though a more clearly moralistic film in some ways, also has telling scenes where the protagonist has a mirror held up to him – in one case by a man who might otherwise have been stereotyped as a slimy villain – and is made to see how self-defeating some of his idealism can be. But more than looking only at this film itself, I think it’s worth looking at it in the larger context of Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s career.

As we arrive at the fiftieth anniversary of Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Satyakam – still one of the director’s less-seen films, even though he repeatedly called it his own favourite – I am reminded of two Satyakam-related anecdotes I heard first-hand. One was from Sharmila Tagore, who starred in the film; the other from someone who was intensely influenced by it and would go on to a career in the arts.

During a chatty panel discussion at a Kolkata literature festival in 2016, Tagore recalled an incident during the Satyakam shoot near Jamshedpur where a group of youngsters tried to disrupt the shoot. Dharmendra pulled one of them across by his collar, Tagore told us (“and have you seen the size of Dharam’s hands?”), and gave him a couple of slaps.

“Well, we did that sort of thing in those days,” she added drily, as the audience chuckled; it was an allusion, a mildly self-critical one, to a time when privileged people often engaged in “haatha-pai” without thinking too much about it. (Which is not to say that things have changed much in today’s India.)

The story is amusing if you’re the sort of person who easily confuses the tone of a film with the circumstances in which it was made – or if you confuse actors with the roles they play. (Think of all the commentaries lamenting that Amitabh Bachchan has become so much of an Establishment Man, in contrast to his star-making parts as the vigilante who took on the system –ignoring the fact that Bachchan was close to the “establishment”, the Nehru-Gandhi family, long before he became an actor.) In the context of Satyakam, the character played by Dharmendra, Satyapriya, is an unalloyed idealist, an incorrigible truth-teller, and probably conceived as a Gandhian; the film, based on Narayan Sanyal’s novel, was made in Mahatma Gandhi’s centenary year, and was intended partly as a homage. It’s impossible to imagine someone like Satyapriya getting physically aggressive over a mild provocation.

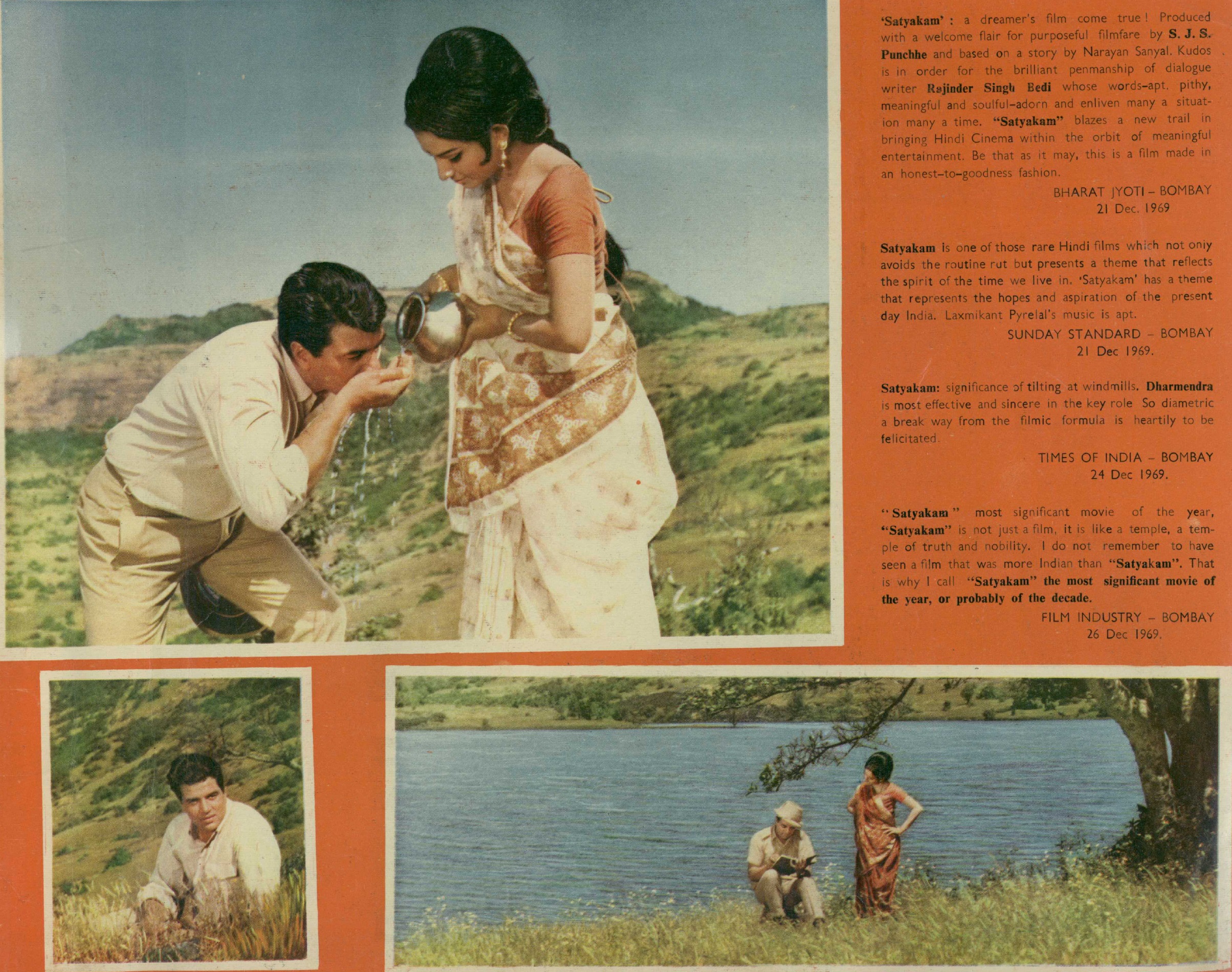

Satyakam is about a man who refuses to compromise on his principles even if it imperils the people who depend on him From the film's original 1969 song-booklet. Picture sourced by the author

Jai Arjun Singh is a Delhi-based freelance writer and critic who writes mainly about books and films. His book The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee was published in 2015 by Penguin

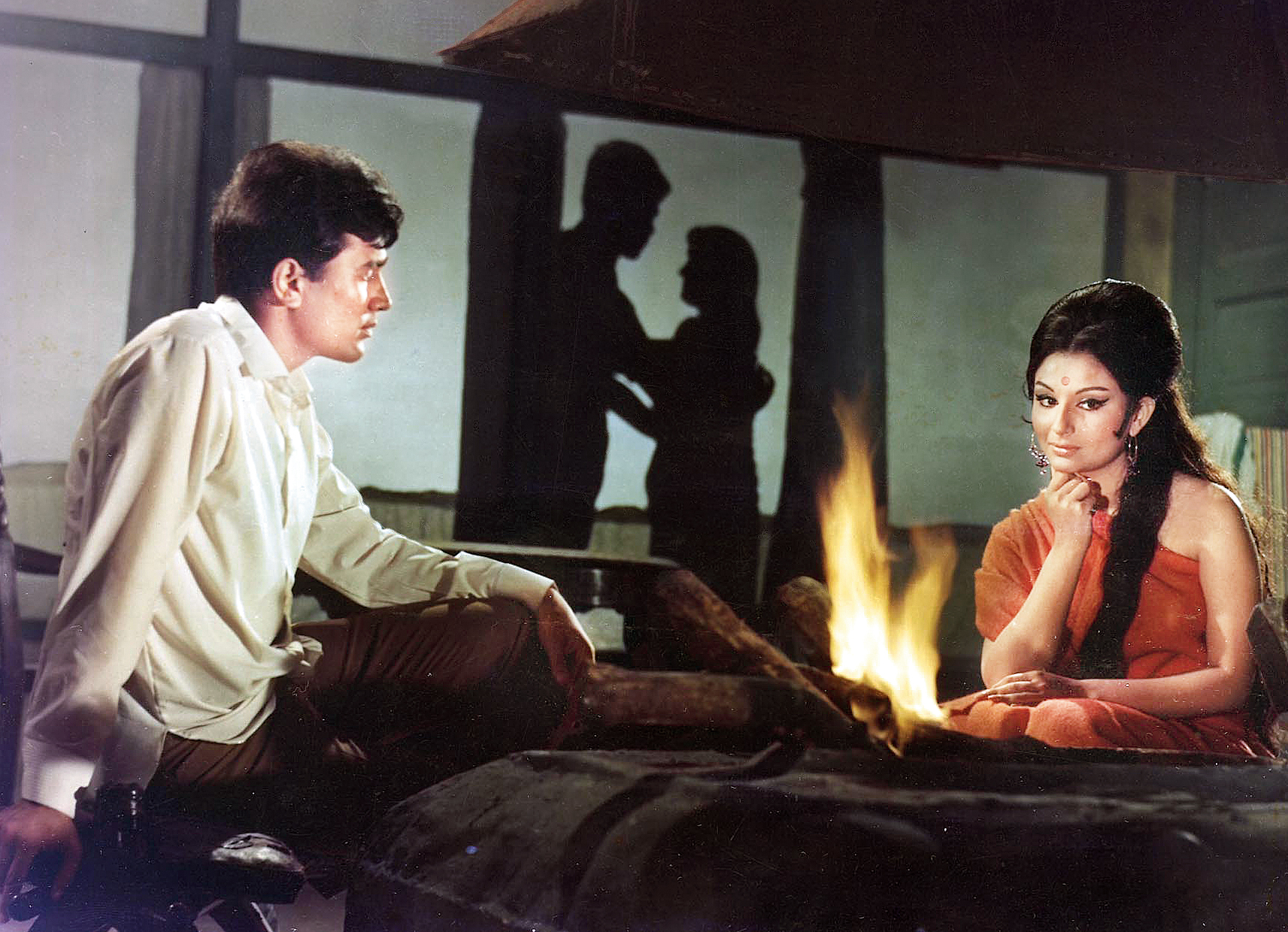

Dharmendra and Sharmila Tagore starred in the 1969 film From the film's original 1969 song-booklet. Picture sourced by the author