Exactly midway through the just-released Season 2 of the David Fincher-produced show Mindhunter – a dramatisation of the FBI’s profiling of incarcerated serial killers in the 1970s and 1980s – the legendary Charlie Manson shows up. He begins his meeting with the two agents who have come to interview him by impishly sticking out his tongue at one of them, Holden Ford (who is something of a Manson fanboy). And he ends the encounter by signing a copy of a book Holden has brought with him: “Each night as you sleep, I destroy the world,” Manson writes, with all the confidence of a man who knows he is a celebrity, even though he will never leave jail.

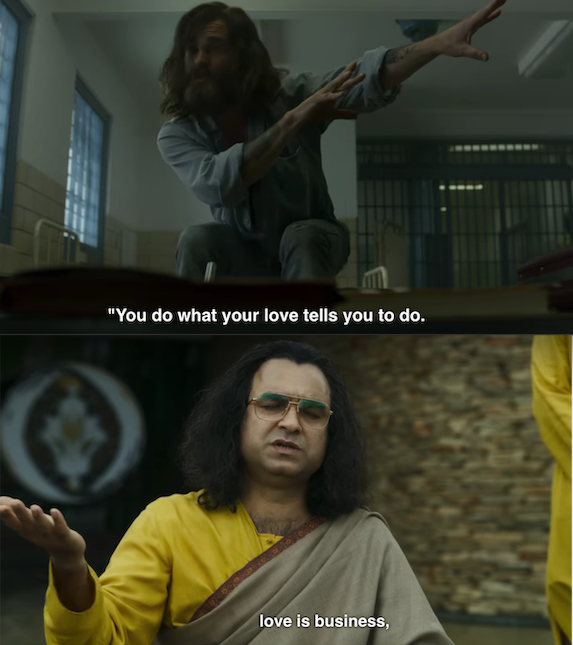

Manson – who mentored wayward youngsters into committing multiple murders in the late 1960s – is played by the same actor (Damon Herriman) who briefly plays the part in the new Quentin Tarantino film Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. And yet, when I watched this Mindhunter episode, I wasn’t thinking of Tarantino’s film. I thought instead of another mad prophet in another recent show: Khanna Guruji, played by Pankaj Tripathi in season 2 of Sacred Games.

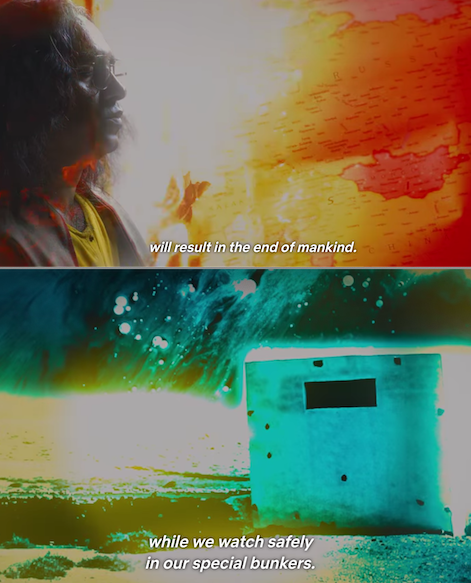

This omniscient-seeming godman runs an “ashram” in Croatia, becomes spiritual guide to the tormented Ganesh Gaitonde (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) – and eventually, speaking in the same benign tone as always, reveals his plans for the end of the current world and the emergence of a “pristine” new one. From the corrupt Kali Yuga that we are now living in, Guruji says, we need to return to the Satya Yuga of yore. In his view of things, Time will coil back on itself – like a Möbius strip, perhaps – but it might need a little push. So let’s detonate a nuclear bomb in Mumbai, and wait patiently in underground bunkers while the world ends. We’ll come out later.

The parallels between Guruji and Manson are striking, even if the scales at which they operate are very different. In Mindhunter, just before meeting Manson, the agents discuss another pseudo-godman who gave himself the name “Krishna Venta” and led a religious commune in California in the 1940s and 50s. “Krishna said he knew a secret place in the desert where he and his flock could wait it out. Then, when the war was over, they’d emerge and create a new civilization.” Manson had spent some time with this commune and probably got a few ideas from there – it is widely accepted now that he claimed the “helter-skelter” unleashed by his followers would help start a massive race war in America (though the Manson we meet in that Mindhunter scene has a grand time hedging and prevaricating about his activities).

So here are preachers who talk a great deal about love but promise an apocalypse – all the while ensuring that their own interests are safeguarded. They are charismatic, they have large followings, they succeed in brainwashing many apparently sensible people.

“What we need to find out,” says an FBI agent, “is how a diminutive, uneducated ex-con convinced a group of middle-class teenagers to brutally murder seven strangers.” There was clearly something in Manson’s personality that cast a spell on those youngsters, and it continues to be felt decades later: in online discussions of serial killers and serial-killer movies, he is often treated as a folk-hero. (Watching Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, during the intermission I heard a viewer telling his friends in a fawning tone, “That guy who came to the house was Charlie Manson, dude! Didn’t you get it?”) In Sacred Games too, Gaitonde is initially intrigued by Guruji when the latter makes an accurate prediction during a phone conversation – but later, he becomes a true bhakt because the guru’s spiritual mumbo-jumbo touches a chord in him, given the troubles and self-doubts he is going through.

Personality cults aside, perhaps there is something inherently seductive about the idea that the present time is just maya or illusion, that something much better, much “purer”, lies around the corner – and that in order to get to this utopia, a nasty storm will have to be weathered and there will be many fatalities (or sacrifices). It’s the sort of thought that combines idealistic yearning with a darker, destructive impulse in human nature.

A version of this idea also exists in the narratives created by many bordering-on-dictatorial governments around the world: whether in First World countries trying to keep out immigrants or the ongoing attempt in India to promote an extremist version of Hindutva and to shut down those who might be in opposition to this. We see it in the astonishing statements made by people in high places, including prime ministers and chief ministers who speak of how ancient India (an uncontaminated Hindu rashtra in their view) had made more scientific progress than the world has today. We had everything: planes, plastic surgery. Best of all, we had no Mughal invaders. We can return to that time! Even minorities – Muslims, Dalits, women – can come along for the ride… just as long as they know their place in the hierarchy and toe the line.

Sacred Games makes a few sly references to the ongoing political climate. “Internet ka istmaal karna seekho (Learn to use the internet),” Tripathi’s Guruji tells his followers in a scene that is set around the turn of the millennium – he believes that the then-nascent worldwide web will play a big part in his mission. It’s easy to see how this scene could be a comment on how shrewdly the BJP and its large IT cell have bent social media to their own purposes over the last few years.

Though it’s obvious that the real-life psychopaths portrayed in Mindhunter and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood did a lot of damage and caused untold grief, most of them at least got their comeuppance and were removed from spaces where they could continue to be a threat – only allowed to feel important in short bursts when FBI agents came to meet them or novelists wrote books based on them. On the other hand, when you look at people in positions of power around the world – including politicians and corporate honchos with their own agendas, promoting bigotry, fantasising about purity, pretending the climate crisis doesn’t exist – those serial killers start to look like very small fry. An old, always-pertinent question raises its head again: are the true lunatics in the asylum, or running it? And are we lemmings on a precipice, set to follow a dangerous new breed of gurus into the abyss?

The parallels between Guruji and Manson are striking, even if the scales at which they operate are very different Screen shot from Sacred Games 2 (above) and Mindhunter

Both Sacred Games and Mindhunter are available on Netflix

Jai Arjun Singh is a Delhi-based freelance writer and critic who writes mainly about books and films