He was 58. I was 26. He was a giant of Indian cinema, having brought the New Wave. Celebrated in the biggest European film festivals. The year before he had won the Silver Bear at the Berlinale for Akaler Sandhane.

I was a desperate theatre actor and director, whose Bengali adaptation of Weiss’s Marat/Sade, sponsored by Max Mueller Bhavan, was pulled off the stage by the audience for being promiscuous and perverted.

I received a call from the newspaper where I used to work a year ago, saying that Mrinal Sen was looking for me. As a journalist, I had briefly met him two years ago. I called back. He came over to see our rehearsals. He ended up casting me in the lead for his film Chaalchitra.

So began a 43-year-old relationship. The most cherished friendship I’ve ever had. Funny, wacky, compassionate, argumentative, filled with differences, and deeply human.

He was, as he claimed, a private Marxist. I was and still am an individualist.

Mrinal Sen is the most modern man I’ve ever met. I’ve met quite a few legendary souls at home and abroad. Quite a few giants of cinema, theatre, and other arts. Yet, Sen or “da” as I called him, is still the most exciting, most contemporary, unabashed human being I’ve encountered, who despite our differences, taught and influenced me in such a unique way. If you know him closely it’s impossible not to love him.

The only Indian filmmaker whose entire body of work is consistent in attempts to break his own style and method. In a world constantly trying to reach perfection, he stands out as the sentinel of that which is “beautifully imperfect”. His characters are always flawed. His narrative constantly challenges the prevalent paradigm. His style differs radically with each film. Stubbornly non-conformist, definitely disturbing. Thus he earned numerous labels — “maverick”, “gimmicky”, “crow film-maker”, “pamphleteer”, “non-committal”, “too abstract”…

As we in 2023 celebrate his 100th birthday, we all know that this planet is damaged and nothing can ever be perfect, least of all a story or a film.

Very personally, his package from Bhuvan Shome in 1969 to Chorus in 1974, is his most exciting contribution. The phase for which he was severely criticised yet which brought the Indian New Wave and got him international acclaim. All six black-and-white experiments (including Interview, Ek Adhuri Kahani, Calcutta 71, Padatik) will remain milestones in Indian cinema for their highly radical structure. Perhaps too dynamic in style to be inherited, in a nation that still gropes to tell perfect, antiseptic stories. They reflect a Master way ahead of his time, who dared to challenge the audience with his style and structures. Despite having reservations towards Left partisan politics, I am still enamoured by these radical structures. The wit, the humour, the sheer joy of watching cinema that provokes you. They are not rounded stories but comprise moments of absolute brilliance.

His Chaalchitra, for which I bagged the best maiden acting award at Venice in 1981, is a freak. The producer turned bankrupt and the film was not released. Yet to me, it’s Sen’s most underrated, most modern film, which was ignored for having too thin a plot. Much later in his retrospective at La Rochelle in France, it was hailed for being a modern extension of neo-realism. To me, it’s a film about searching for a film. The protagonist Dipu searches for a story. When he finds it, he has to compromise. This idea itself is uniquely modern and deeply existential. It’s here that I connect with him.

This “searching” has been the unique aspect of all of Sen’s films, which set him apart from all others. When I joined him, he was “soul searching”. His anguish against the world outside had been replaced by a deep anguish at his own class, his own kind. During Chaalchitra I was swept away by his wit, humour, flamboyance, his sheer physical energy. I was a trained and too desperate an actor by then to have any qualms about the camera. Rather I sometimes misused much of the freedom he gave me and had a ball. I was all set to leave for Germany to work in a theatre company. Returning from Venice, I was practically pushed into a role almost 10 years older than myself, in Kharij. I had to work hard at putting weight on my scrawny, gawky physique and become a settled-down Anjan Sen. Mrinal Sen’s heavy turtle neck, his shawl, lots of beer, and the moustache I grew, somehow helped me pass.

During the shoot of Kharij it was a different Sen. A far more restrained, austere, intense Sen. Improvisations were still on, but much more intense and from within. I sometimes wondered whether it was the same man I worked with a year back. I had already bonded deeply with him. Just the next year, I rediscovered him. It was this constant rediscovery over the years that kept our bonding intact. Despite my political differences, our arguments, and my radically different choices, the space he and his family always offered was so dynamic that I could never, ever think of losing it.

When he took my play Dewal, which I wrote after the breaking down of the Berlin wall, and made a script from it, he completely changed the ending. I had celebrated the breaking down of the wall. He decided to lament the loss of all those young Naxalites who died for the Leftist cause. We argued over it. The basic story was too dark, so our arguments got darker. I gave in since it’s the basic right of any filmmaker to interpret any material his or her way. When it was showcased at the Berlinale in ‘91, Mrinal Sen could not go for health reasons. I presented the film as the actor

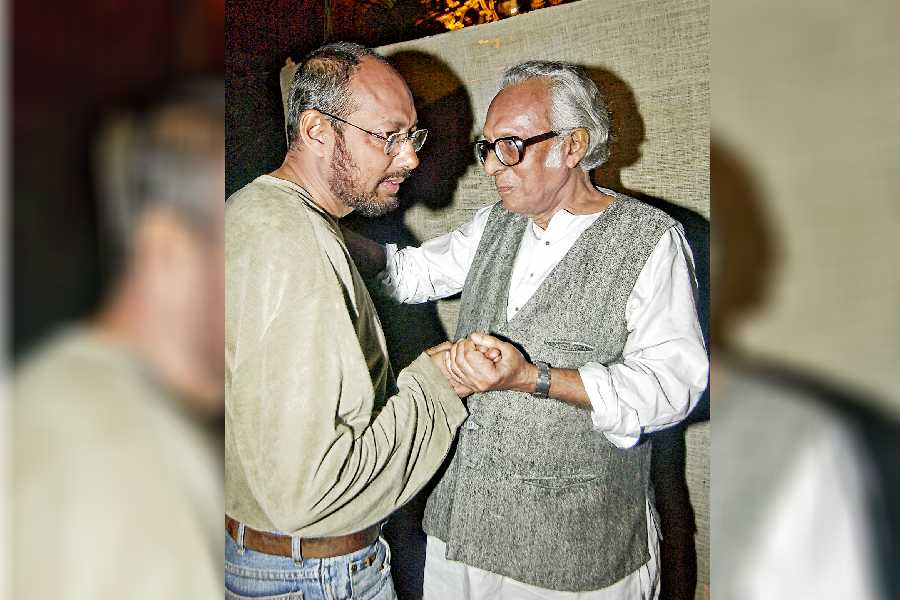

Anjan Dutt and Mrinal Sen

and story writer.

At the post-screening Q&A, I had to take a beating from a large section of the audience, once part of GDR, who vehemently questioned why the film did not celebrate the change. They were people who had suffered the Statsi. I had to argue back and almost unwittingly justified Mrinal Sen’s standpoint, claiming that with all respect for those who had suffered during the wall, I have the right to my belief, my tears. The non-communist that I was and still am, I ended up going against my own belief and convincing them that, “I accept change but also have the right to look at it critically. If you take away that right, you take away my history as well as yours!” A group of elderly audience, convinced of my ranting, took me for dinner. I was so alarmed at myself that I got drunk. Such was the power of Mahaprithibi.

The point is that Sen was and still is perhaps one of those masters who contradicted the so-called logical, simply because he had the inherent latent talent to contradict. He encouraged making mistakes, ‘cause, as always told me, “By making mistakes is how you learn. Don’t ever lose the rough edges of your film, or you will end up making antiseptic, bovine movies”.

One night, after the shoot during Antareen, he said that I was a rather good actor, that he ought to have cast me more. I said why not try a thriller with me? He knew about my love for detective fiction and started talking about a failed man who pushes someone off a cliff and takes his identity. The killer keeps returning to the scene of the crime to check whether he has left any trace or clue. He ends up jumping off the cliff. I told him that he was more an existentialist than a Marxist. He laughed it off. Later we discussed numerous ideas for films which never matured, but never the thriller. After watching my second Byomkesh he was severely critical, saying that they lacked the existential crises my comedies and musicals usually have. He suggested that I should try out his old idea and make it into a great detective film.

The genius of Sen lies in his ability to look at anything beyond the obvious. The older he grew, the less didactic he became. More and more urban. It was his sheer urbanity which attracted me towards him beyond words.

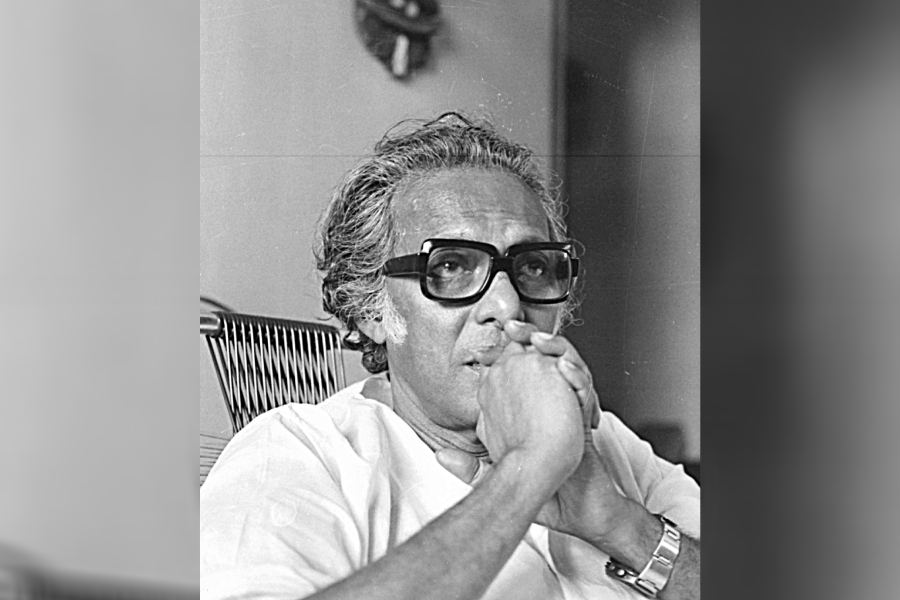

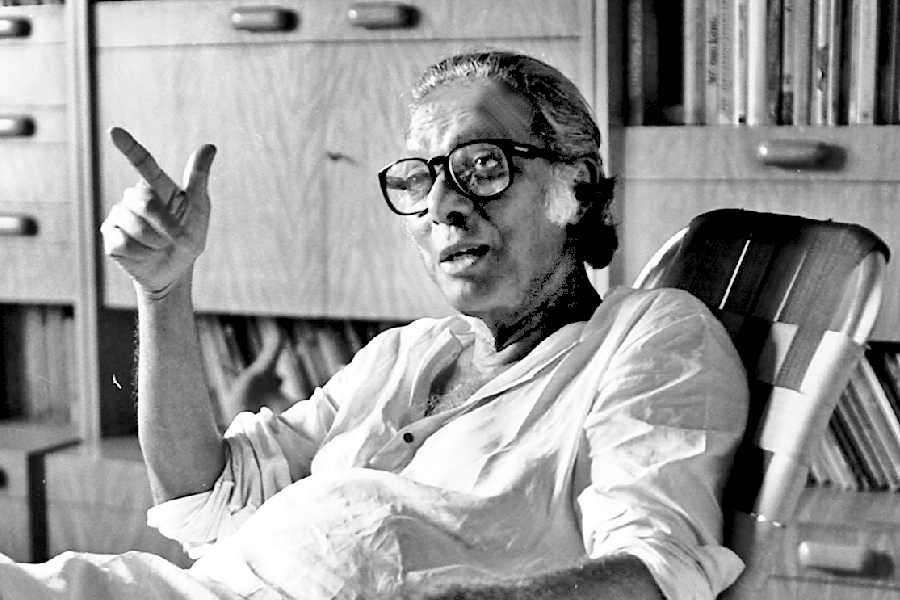

Mrinal Sen

Way back in the mid-’90s, I wanted to make a documentary on him. He agreed, claiming that it had to be personal. The New Wave German filmmaker, Reinhard Hauff had already made a highly exciting documentary on him called 10 Days In Calcutta. A Portrait Of Mrinal Sen. Sen gave me a book on the filmmaker Wim Wenders’ documentary on Nicholas Ray called Lightning Over Water. I read it. Managed to get a VHS and saw the great yet extremely cruel film about Nicholas Ray’s last stages of life. I told Mrinal Sen that it’s the wrong reference.

However, having not found my story, I decided to follow him around with whatever camera I could afford from time to time. Betacam, PD 150, handicam, Canon D… a two-camera set up. For years. I collected almost nine hours of footage. From a highly energetic Sen walking the Hiroshima rally in Calcutta, shooting his Amar Bhuvan, editing, dubbing, releasing, being celebrated at Nandan, giving lectures, at home, on the streets…. He broke his hip. I became bald.

I ended up conducting a one-hour interview, over two evenings. All for a 45-minute documentary. There was a lot of footage, but no personal story. I had stored some of the material in a proper air-conditioned set-up. The rest of it is at home. Sen started using a walker. I decided to stop shooting. I still hadn’t found my personal story. The footage got ruined. Sen asked me whether I was still making the documentary. I told him it’s just footage. I can’t find my story. He was a little disappointed with me. I was more disappointed with myself. Then he was gone…

Perhaps our bonding has been so close that I could not look at a particular story which would define my connection with Sen. He was one person I could open up my heart, my deepest, darkest secrets to. Our friendship was beyond cinema, about values, the sheer relish of sharing our city, its faults, our failures, our dreams…. His family comprised the most endearing folks who were always open-hearted. His wife Gita Sen easily became someone I could blindly trust. His son, Kunal, with whom I connected fleetingly, is still the most witty, sensitive, objective son of a legend, I have met. His friends, his associates, his cinematographer… were all an integral part of my fondness for the man. A house that is still so rare in its modernity. I have never seen sycophants in that house, nor senility. It was a place I could be myself.

He dropped in to see my performances of Galileo, almost every show in 2012, to tell me why it’s better than all the previous productions in Bengali. I told him it’s more raunchy, feisty. To my utter surprise, he said it’s more Brechtian and that I was becoming a Marxist.

When health got worse, he was bedridden, I used to keep going not out of any sense of duty but the sheer joy of being with someone I loved. Transcending the smell of antiseptic and gloom, we laughed and talked about my failures, Terrence Malick, the fun we had making Chaalchtira. During the final months, I was too tied up to visit him. I have no regrets since I believe he is there in me, in the lanes of my city, and in many of us.

It’s only about one-and-a-half years ago that I actually found the story I wanted to tell about him. My personal film about Mrinal Sen. It took years of distance and perspective. So as we step into his 100th birthday, I step into the final post-production of my feature film on Mrinalda. The fact that it’s totally self-financed made the work far more independent than anything that I’ve ever done.

Any birthday is meant to be a happy occasion. A celebration of loved ones. For me, it’s a celebration of a legend I will always love unconditionally, unabashedly. I hope the readers who love his work will look into them and find new meanings they perhaps did not find before. Let us all find a new need for Mrinal Sen. Not the old, hackneyed interpretations. Let’s relook at his cinema with fresh eyes and ears. Find new dimensions. Cinema is not essentially about telling stories. It’s about how you tell them. Sen was always bothered more about “how” and not “what” is being told.

Before writing this article, I looked into that “how” in Akash Kusum (Up In The Clouds) and found it to be “terribly beautiful” in today’s reality. Let’s celebrate that “how”.

Anjan Dutt has acted in several of Mrinal Sen’s films, including Kharij