[This is the concluding part of a two-part article]

For a couple of years, in 1987-89, the power situation in Delhi was abysmal and theatres often cut corners by switching off the AC. So it was that I watched Vinod Khanna’s comeback vehicles Insaaf and Satyameva Jayate in Savitri, being cooked in the heat and humidity. Imagine a 1,000-seater full-house — the craze for Insaaf was unbelievable — with no fans and air-conditioning.

I remember one particular Friday vividly. The Anil Kapoor-Sunny Deol ‘Western’ Joshilaay and the Vinod Khanna-Raaj Kumar flick Surya released the same day. I booked the first day first show (12 noon) for Joshilaay at Savitri and the matinee (3.30pm) for Surya at Paras. It was to be a touch-and-go affair, but manageable, given that the two theatres were about 2 kilometres apart.

I emerged from Savitri and started walking towards Paras. Crossing the road, a bit under the weather (I am not sure if it was the film or the stuffy uncomfortable theatre that was responsible), I failed to see an oncoming scooter that rammed into me, knocking me down. Solicitous passers-by helped me on to my feet and to the nearby bus stop, where I sat for a while. A couple of them offered to take me home. How could one tell them that I had someplace better to go? One of them drove me to the Paras crossing where I said my home was. I walked the rest of the way, and made it in time to see the censor certificate come on for Surya.

By the time the film groaned its way to the interval, I could feel my leg swelling. Limping out to the foyer, I saw a trickle of blood flowing down my legs onto the floor. By the time the show was over, I was almost in tears (the film might have been responsible). Six hours in two theatres with no fans or AC, sweating profusely, bleeding from my injury and in tears with the pain – it was my version of blood, sweat and tears.

Qurbani to Octopussy, flinching in embarrassment

I would have a similar experience watching Where Eagles Dare at Chanakya. Trying to board the bus to the hall, I slipped, fell and blacked out for a few seconds. Concerned strangers held me by the hand and took me over to the bus stand, offering to walk me home. But that was out of the question when Chanakya, Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood beckoned.

The memories are vivid. Watching Qurbani in Savitri, flinching in embarrassment at the thought of Mom and Dad seated next to my brother and me. You really don’t want your elders around when Zeenat Aman croons Aap jaisa koi or Vinod Khanna is all soulful about her on the beach to the strains of Hum tumhe chahte hain aise.

A James Bond festival at Archana with hordes outside the booking window, a resourceful friend climbing on top of the mass of people and somehow managing to get his hand into the booking counter and coming out with the tickets. The cardinal error of watching Octopussy with your parents (this was my first experience of the spy I came to love so much, and I would not repeat the mistake). Making friends with the gatekeepers so that they would look out for tickets at the coveted first day first show. I still remember the bald and bearded hunk at Savitri who never smiled but invariably nodded in recognition and who would often warn me, particularly with films like Gangaa Jamunaa Saraswathi, ‘Kyon sir-ji, bekaar time barbaad kar rahe ho.’ Or the man at Regal, who told me, vis-à-vis Prem Aggan, ‘Paise zyaada ho rahein hain kya, sa’ab.’

Watching Shahenshah and Hum with the whole extended clan and more, including my grandmother who never seemed to mind the bad theatres and the worse films. The last picture shows — Raj Kapoor’s Sangam and Mera Naam Joker — at the once-majestic Regal in Connaught Place; majestic even in 1989 when I took my grandmother to a morning show of Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, now falling apart, without AC, and with the noise of fans whirring drowning the dialogues.

Booking tickets was no child’s play

And the excitement of the first day first show itself. No Bookmyshow. No Paytm. Booking tickets was no child’s play. You went through the ordeal because of the world they promised once you had them in your hands. Advance bookings would open on Mondays. And you had to be a really early bird to get tickets for the 12 noon show on Friday.

Even as late as 1993, I stood for over a couple of hours to get tickets for Jurassic Park. The buzz outside the theatre on opening day, with touts whispering black-market rates, and fights breaking out at booking windows. The sense of satisfaction one felt if one had tickets when a board outside screamed ‘HOUSE FULL’ and those not lucky enough to have gained admission approached you for a spare ticket.

The barely concealed anticipation as one stood in the foyer, waiting for the doors to open, making conjectures about the film from its promotional stills on display (‘Yeh film ka suspense hain,’ I still remember a friend telling me pointing to Amrish Puri’s memorable Loha get-up – he meant ‘villain’ but was too excited to get the word right). Then, as the ushers opened the doors, the frantic run. Because the middle- and front-row tickets often had no designated seat numbers, and so getting a seat a fair distance from the screen, thus sparing you a bad kink in the neck, often depended on how nimble-footed you were. And then magic that made all that has gone before worth it: the audience stomping its feet in the aisle and on the seats when Anil Kapoor went ‘One two ka four’.

The high-end Chanakya and falling in love with English cinema

Then there was Chanakya. Unlike the Savitri-s and Paras-es, Chanakya was high-end. While most theatres had a balcony, a rear circle, a middle circle and a front circle, Chanakya also boasted two elevated side wings hovering between the balcony and the rear circle. It also had the finest sound system. So that the audience shrieked as one at the iconic chestburster sequence in The Alien.

Few experiences since have measured up to the thrill of watching an Alfred Hitchcock festival here – including Psycho (the collective audience gasp its sequences evoked is still fresh in memory), North by Northwest, Vertigo, Rear Window, 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes (for which my brother and I waded through torrential rain and knee-deep water at Chanakyapuri’s railway bridge). Or a festival of Westerns, including Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy (the romance of its rousing soundtrack multiplied manifold in the stereophonic ambience of Chanakya).

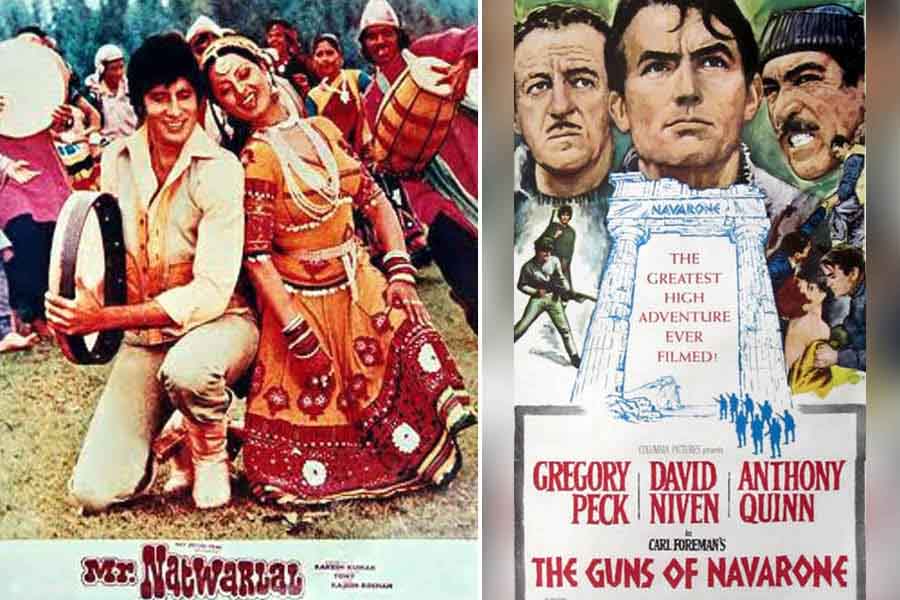

And of course The Guns of Navarone, which kindled my love for English cinema. Geraftaar had just released in the theatres and as an Amitabh Bachchan fan my excitement was palpable. One Sunday, we planned an outing at Paras to watch it. Except that Dad changed his mind after we left home, so that instead of the short walk to the theatre, we undertook the long bus ride to Chanakya which, in the words of Dad, was screening an unforgettable film with Gregory Peck and Anthony Quinn. Of course, as far as my brother and I were concerned, that was laughable. Unforgettable? Vis-à-vis Geraftaar? Who in the right frame of mind opts for Gregory Peck and Navarone over Amitabh Bachchan and Geraftaar? What was Navarone? Where was Navarone? Who was Gregory Peck? My brother and I muttered our disapproval and displeasure all the way to the theatre.

By the time we left the theatre, however, the two of us had been converted. On the way out, we pleaded with Dad to book tickets for the next change, To Sir with Love. And thus began my lifelong affair with English cinema. I dare say, the ambience of Chanakya, the grandeur of its screen and sound as we thrilled to that to-die-for cast played a crucial part in that. (I watched Geraftaar years later on the VCR and I have always thanked Dad for the change of plans that life-altering Sunday afternoon.)

Gone are the old familiar places

Today, watching Hera Pheri and Kaalia in a plush 200-seater with reclining seats, the air redolent of perfumes, it is impossible to imagine a theatre like Chandralok in C.R. Park, where I watched Mr. Natwarlal and Pratiggya. Where you could hear the dialogues even if you stood on the road outside the hall. Or hear a fight break out outside even as you watched a film.

Forget Dolby and Surround, the theatre wasn’t even soundproof. Sparrows twittered and hawkers ferried their wares (chai and jhalmuri) even as Amitabh Bachchan and Dharmendra went about plying their trade. Or that theatre in Kolkata a close friend often mentioned wistfully. One that had a municipality nullah flowing through it between two rows, so that when it rained outside, a legend would appear on screen: ‘Daya kore apnara chappal jooto tulay neben.’ (Please pick up your shoes.) Lest the nullah overflowed and took away with it the footwear the viewers preferred to leave on the floor while they tucked their legs on the seats.

Paraphrasing Charles Lamb, ‘All, all are gone, the old familiar places.’ Yes, nostalgia is always a bad judge of the experience one has had. It clouds rational appraisal. The past is always more sepia in our thoughts than it actually was. However, even as I watched the Lord of the Rings trilogy at the refurbished PVR ECX Chanakyapuri, my mind went back to those distant Chandralok afternoons. Even as I pass Paras every day on the way to my son’s school, I cannot help but feel a pang at a beloved crucible of my youth having given way to a handful of bland eateries.

(Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer)