Elton John is not a nostalgist. Neither is his songwriting partner of more than 50 years, Bernie Taupin, who supplies the lyrics that inspire John’s melodies. “I think one of the keys that has driven us all these years, it’s the fact that we never look back,” Taupin said.

But now the world can witness their history, thanks to Rocketman, the musical fantasy that traces John’s transformation from the piano prodigy Reginald Dwight, born in a hamlet outside London, to the over-the-top showman (played by Taron Egerton) with a slew of global hits. He met Taupin (Jamie Bell onscreen) by chance after both answered an ad in a British music magazine.

The film, directed by Dexter Fletcher and co-produced by David Furnish, John’s husband, is unflinching about John’s rise, his childhood trauma and subsequent addictions. “I’ve never been a half-measured person, and you can see that got me into a lot of trouble,” John said. (He’s been sober since 1990.)

The depiction of his life as a gay man has — to his dismay — led to the film’s censorship in Russia and Samoa. But, he said, “I didn’t want to leave any of the sex scenes out, because that’s very important — that’s why we went for an R film. It’s not Bohemian Rhapsody,” also directed in part by Fletcher. “My life is not a PG life.”

At 72, John remains artistically engaged — in the midst of a farewell tour, and still composing for films and theatre (the Lion King remake; a musical version of The Devil Wears Prada). He splits his time among multiple homes with Furnish and their sons, ages eight and six.

In separate phone interviews — Taupin, 69, from his home in California, and John from a tour stop in Copenhagen — the pair discussed putting their lives on film. Excerpts.

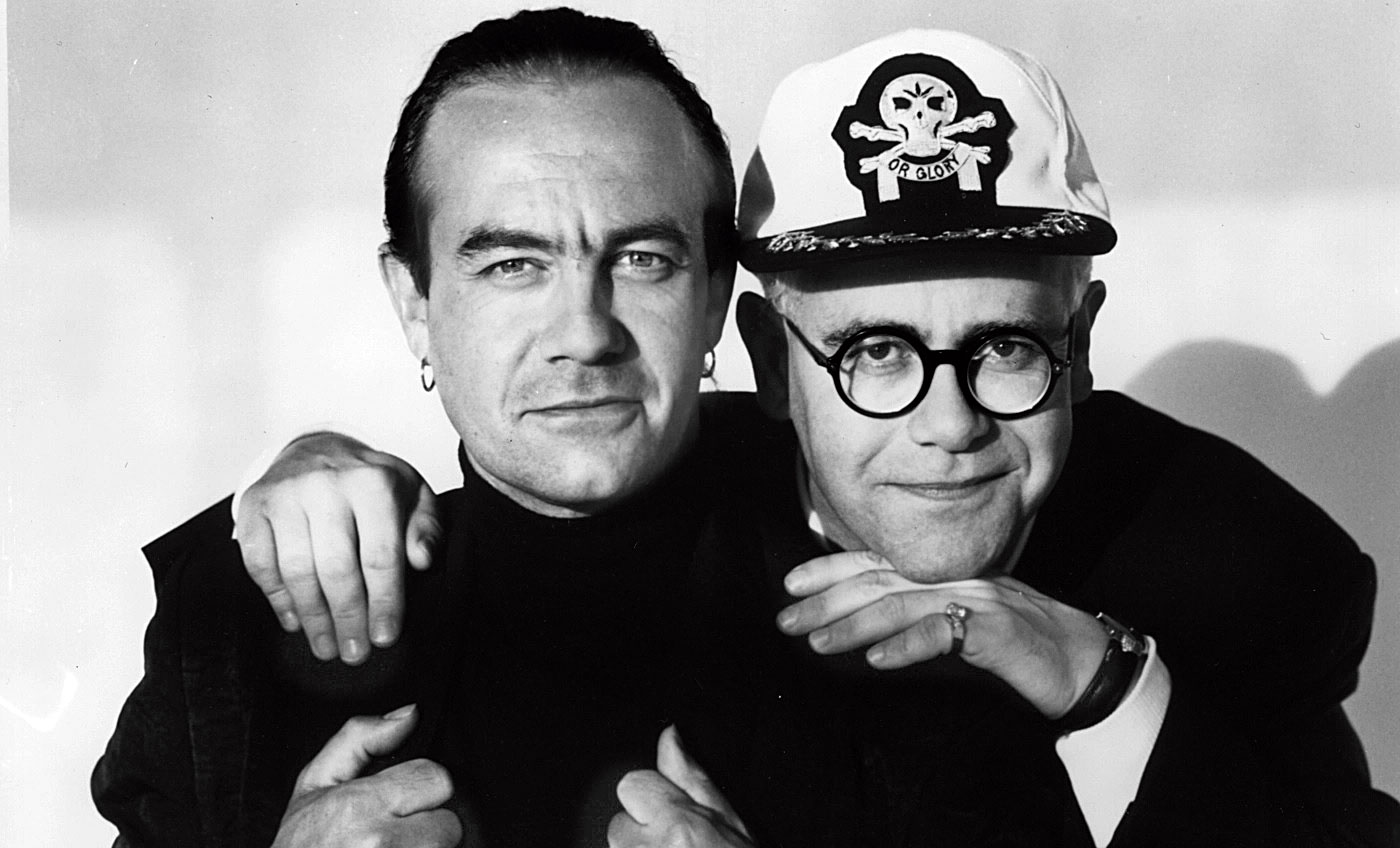

Elton John and Bernie Taupin. Picture: Herb Ritts

Is the movie hard for you to sit through?

Elton John: The first time I saw it was in January or February, a very rough copy, and that was when I got the most emotional, because I just didn’t know what to expect. It certainly had a huge impact on me, especially the family stuff and the Bernie stuff. It makes me happy and it makes me sad. I think the film eventually is about redemption, and how anyone can get redemption, if they try.

Elton, you spent your early career hiding your identity and your demons. Was it cathartic in a way to dramatise it so openly?

Elton: Of course. Even though it’s hard to watch what you’re going through and what you did to yourself, I find it cathartic. I’ve always tried to be as honest as I can, since I got sober. I think there’s no point in sugarcoating anything — this is what happened, this is how I behaved, this is a real sad story of someone who was trying to get to grips with his past, but was extremely famous — onstage is where I felt at home, and offstage, I didn’t.

The film could’ve started with your self-invention as an artiste. Why include the most painful parts of your childhood?

Elton: My childhood really shaped the way I became as an artiste, because I was determined to prove myself to my father, that I could be successful and I could do it my way. It shaped me into the performer that I am. I didn’t need to prove anything to myself; I just wanted to prove something to him.

I grew up in a very, very hostile environment between my parents. Basically — I’ve had years to reflect on this — they should never have married each other. They were unsuited and had miserable times together, and as a result I suffered from it, because they argued about me. It was the ’50s — divorce was deemed to be scandalous, and so I was stuck in the middle of two very unhappy people. As I look back on it now, I don’t blame either of them. I mean, they both lived a loveless marriage, and the nice thing about it is, when they did remarry, they both had very happy marriages. And I’m very happy about that for them.

Do you think you can be a great artiste without experiencing, or overcoming, early trauma?

Bernie: I would’ve had to have done it to know. We both had tremendous trauma in our lives, to be quite honest. I can’t think of any real major artistes that probably hasn’t. I had addictions of my own — I wasn’t any fairy tale prince. Sadly some of us don’t come through it. Certainly Elton was extraordinarily lucky to nip it in the bud in the right time.

Elton: My career mushroomed so quickly, from 1973 onward — I made two albums a year, different singles, B-sides, I toured, I did radio. I was on a high, but it wasn’t a drug high; I was on adrenaline, and sooner or later you crash and burn, and unfortunately the drugs helped me crash and burn. You know, two days before I was at Dodger Stadium [in sold-out concerts in 1975], I was having my stomach pumped.

How did you keep going onstage, and into the studio, rising to the creative moments during your addiction?

Elton: That’s what kept me alive. During the hard times, I still kept myself busy. I didn’t shut myself away and just do drugs, which a lot of people do and they disappear for two or three years. You can say that, initially, music saved me — the most incredible part of my childhood was the music. And then when I came to the difficult part of my fame, the music still saved me, because I still worked, and I still made records. And if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t be talking to you right now.

Bernie, when Elton went to rehab in 1990, did you think it would stick?

Bernie: I really did, because the thing about Elton is, it’s all or nothing, all the time. When he sets his mind to something, nothing can break that change. That scene in the film when I visit him [in rehab], and he’s mopping the floor, I remember how much he enjoyed doing his own laundry, mopping the floor, scrubbing the toilet. Once he was in that situation, he adhered to it 100 per cent, he totally embraced it. That shows his character.