Smriti Mundhra almost does the impossible with The Romantics. Over its four-episode runtime, I almost bought into the Yash Raj Films (YRF) magic. I, who had always dismissed the production house as makers of ‘namby-pamby’ films – Shah Rukh Khan uses that term, referring to his first reaction to the film that catapulted him and the production house into the stratosphere, Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge – was suddenly looking up their website, checking what I had missed. And I was actually nodding at and agreeing with Aditya Chopra, who gives the word ‘reclusive’ a whole new meaning, whose reluctance about facing the press makes the likes of Greta Garbo and Suchitra Sen seem hungry for the paparazzi.

I have never been a fan of the Yash Chopra school of romance. Its woman-in-white dance of distress, its strawberry and ice cream world, its fair-and-lovely women in the flimsiest of chiffons and its well-groomed men in turtlenecks and leather jackets always left me cold. Silsila epitomised a ‘dishonest’ film with a climactic resolution that even a first-time director should be ashamed of. Chandni was a pretentious overwrought work with an atrocious Sridevi performance that I never managed to sit through again after the first time I watched it. The former at least had some of Hindi cinema’s finest songs; the latter not even that.

Even Kabhi Kabhie failed to move me, though I admit that watching it the first time, in the impressionable teens, the unconsummated love between Amit and Pooja did strike a chord. However, in repeat viewings, the characters and their responses came across as mannered (barring Waheeda Rehman, and a couple of fraught sequences involving Shashi Kapoor, Amitabh Bachchan and Rakhee).

As the megaphone passed from father to son, I could never forgive the makeover they gave the Shah Rukh Khan I adored, robbing him of the edge of Darr, Baazigar, Anjaam and Kabhi Haan Kabhi Na, even Yes Boss and Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, deep-sixing all rebellion in cinema for a generation, replacing it with saccharine inanities like ‘it’s all about loving your parents’. Horror of horrors, even Amitabh Bachchan, who symbolised the anti-establishment and dismantling the status quo in Yash Chopra’s Deewaar, Trishul and Kala Paththar (come to think of it, these were as much Salim-Javed films), became the upholder of stifling maryada, niyam and anushashan in Aditya Chopra’s Mohabbatein.

In short, I had no love lost for either YRF or Aditya Chopra. I regarded all the media speculation on the latter’s blanket ban on any public appearances as much ado about nothing. What’s the big deal? I thought. The Romantics, at least over its four-hour narrative, made me wonder if it really is.

Aditya Chopra, someone you who can’t help admiring

The Aditya Chopra of The Romantics is someone you cannot help admiring. Here is someone who breathes cinema. Someone who has actually altered the landscape of the movies in this country. You get a palpable sense of the revolution he has wrought in the entertainment space. Not one aspect of filmmaking – the production, distribution, casting – has been left untouched by what he has done.

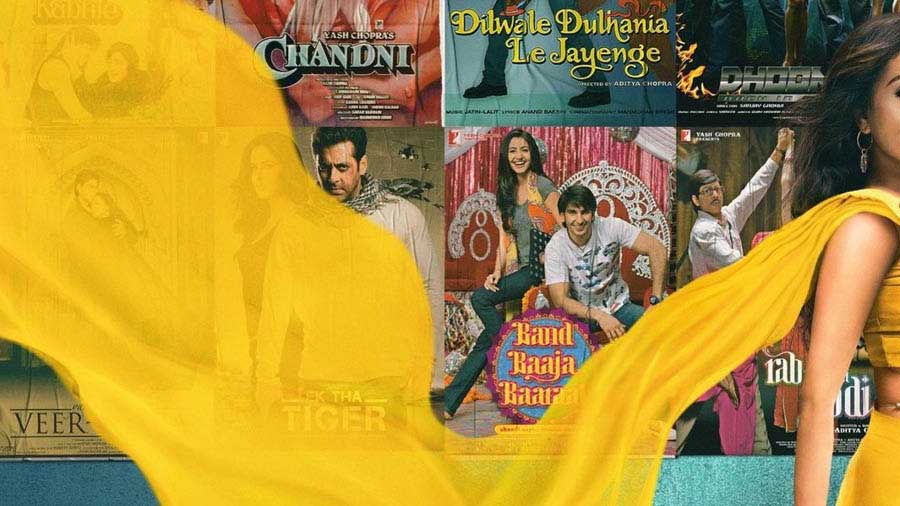

And you cannot help going along with him as he articulates his vision, his drive, his indefatigable energy, and the way he backed films that one does not quite associate with YRF – little unheralded gems like Titli, Aurangzeb, Rocket Singh, and the more celebrated ones like Chak De India!, Band Baaja Baaraat, Bunty Aur Babli and Dum Laga Ke Haisha. So complete had been my identification of YRF with films like Hum Tum, Salaam Namaste, Ta Ra Rum Pum and Fanaa, and that particular brand of cinema, that these others seldom registered as YRF productions.

No wonder then that the best bits of The Romantics are the ones that feature Aditya Chopra talking. And he makes an entry worthy of the many hero entries of the films he produces. The last shot of the first episode ends tantalisingly on an empty chair placed next to a window, on which we see him materialising in the fifth minute of the second episode, asking ‘Where do I begin?’

How can you not take to someone who calls Dhoom a coming together of Manmohan Desai and Michael Bay? As you listen to him, you get the sense of being in the presence of an astute businessman who understands the world inside out. After ushering in the NRI romance with Bollywood in DDLJ, he is perceptive enough to go full tilt to the opposite end of the spectrum with Bunty Aur Babli, and films that explored small-town India. He mentions Indians being an aspirational people and he tapped into those aspirations at just the right time with both DDLJ and Bunty Aur Babli. And he is, at least comes across in the series, receptive enough to greenlight projects dealing with ‘worlds I don’t know anything about’. It is quite a revelation to hear Jaideep Sahni talk about how Chak De India! got Aditya’s nod and Maneesh Sharma narrating how he turned producer with Dum Laga Ke Haisha.

Uday Chopra’s reinvention owes a lot to nepotism

The filmmakers don’t dodge the N-word either, though it could have done with a little more incisive exploration. Here again, Aditya comes across as someone who has created an ecosystem with ‘outsiders’. Anushka Sharma, Ranveer Singh (who narrates a charming tale of Aditya persevering with him despite his atrocious audition), Ayushmann Khurrana, Bhumi Pednekar, and a whole line-up of behind-the-scene talents like Shanoo Sharma and Maneesh Sharma have all emerged from YRF and have no cinematic lineage whatsoever.

Then there’s Uday Chopra, the ‘child of nepotism’. Aditya is disarmingly honest in describing him as ‘an actor, not a successful one… the audience did not want to see him the way he saw himself’. Uday then becomes the litmus test of YRF and Aditya pleading not guilty of nepotism, though The Romantics merely skims the surface of the debate, with none of the other respondents — Abhishek Bachchan, Ranbir Kapoor, Karan Johar, Saif Ali Khan – asked the question. Also, the film does not address the very important fact that Uday getting the many chances he did and managing to reinvent himself owes a lot to nepotism.

Uday, however, is the film’s other strong suit. From the first time we see him, asking the anchor about the preferred accent (‘I can do an English accent,’ he says), he is the one voice who comes across as down-to-earth honest, analysing himself, his ambitions of making it as an actor and his battles with the constant ridicule he has faced, eventually making peace with what is not to be.

No independent, impartial take on YRF’s contribution

Unfortunately, most of the other 30-odd respondents add precious little to the narrative or understanding of either Yash Chopra or YRF or Aditya. We do have Abhishek offering a couple of nuggets (remembering Aditya as a ‘tyrant’ during their schooldays) and Karan Johar admitting that he hated Aditya when they first met. Most of the others are fawning so much, are so aware of the need to be on the right side of the production house that you get precious little that is valuable. Seasoned journalists like Anupama Chopra and Tanul Thakur are the major disappointments. Is there anything more stale than offering Amitabh Bachchan’s angry young man as the cinematic ‘backlash’ against the inequities of the 1970s? Are there no better, more incisive insights into what the legacy of Yash Chopra and YRF might be?

I used the word ‘almost’ in the first sentence of this feature for a reason. Once you dwell on the film a bit, once you are free of its immediate spell, you realise that there were no uncomfortable questions at all. The respondents are almost all people who have worked with YRF in various capacities, so there is no independent, impartial take on its contribution. It’s also later that you realise the absence of Javed Akhtar, Rakhee, Honey Irani – people who have made a substantial contribution to the cinema of Yash Chopra and YRF.

There’s also little engagement with big box-office duds of the past year. Aditya mentions the box-office failure of Befikre sheepishly, in passing, and dwells at some length on the commercial failure of Mujhse Dosti Karoge as a lesson, but there is nothing about the lack of any innovative or cinematic/artistic vision in clangers like Mohabbatein, Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi (what an atrocious premise the film has) and Befikre. Or for that matter in the latter films of even Yash Chopra. Here is someone regarded as a game-changer as a filmmaker. Do his last films even merit mention let alone being hailed like they are? Akira Kurosawa made films like Kagemusha and Ran, Dreams and Madadayo well into his 70s and 80s. Sidney Lumet’s final film, at age 83, is Before the Devil Knows You Are Dead. Do inanities like Veer Zaara, Dil Toh Pagal Hai and Jab Tak Hai Jaan deserve the applause they get, let alone being called ‘classics’? These are uncomfortable questions that no one is asking.

(Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer. The views expressed in this article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the website.)