Near the end of episode five of the new Amazon Prime show Mirzapur, two very drunk friends have a conversation about the romance and poetry of killing with a razor blade as opposed to a gun. “Iss se maarna kala hai” (“Killing with this is an art”) one of them says, caressing his weapon of choice as he dreamily describes splatters and patterns of blood.

Just a few moments after this, such a murder is depicted in grisly detail (though the scene is shot in dim light). And though the men who slit their victim’s face and throat certainly do find poetry and pleasure in the act, we also see the brutality, the ugliness and the suffering up close.

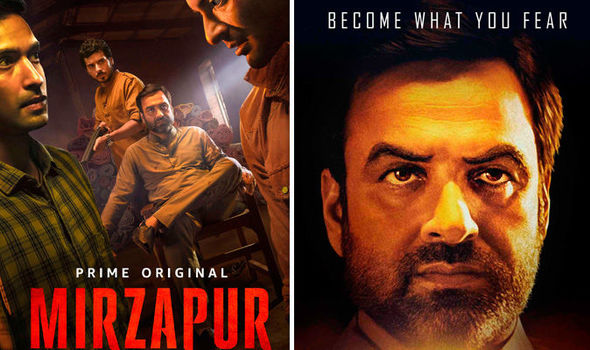

Both these views of violence – its seductive allure and its repulsiveness – run through this nine-part series, created by Karan Anshuman and Puneet Krishna, about the Uttar Pradesh underworld: more specifically, about the life and crimes of Mirzapur don Akhand Tripathi (Pankaj Tripathi), known as Kaleen bhaiya because he runs a carpet business (as a front for the gun and opium trade). The other important characters include Tripathi’s restless second wife Beena (Rasika Dugal), his psychotic heir Munna (Divyendu Sharma), and two outsiders, the brawny Guddu (Ali Fazal) and his contemplative brother Bablu (Vikrant Massey), who become closely involved with this “business” despite the fact that their own father is the one upright lawyer in town.These and many other lives intersect in a story about the difference between being “family” and being “wafaadaar” (loyal), how the need for izzat (respect) can lead people into very dark corners, and the murkiness of student and adult politics (“Agar neta banna hai, toh goonday paalo – goonday banno nahin”).

On the whole, though, Mirzapur blows hot and cold. It has slack moments and detours where we spend too much time away from the really interesting characters (and actors). I couldn’t work up much interest in the distant flashbacks which reveal that even the frail old “bauji” – played by Kulbhushan Kharbanda, sitting in a wheelchair watching macabre nature documentaries on TV –was very much part of this cycle of violence. Most problematically, Munna, who is such a central character with so much screen time (the series both begins and ends with a close-up of his face), rarely moves beyond the gangster-film stereotype of the insecure, entitled, beast-like “prince” of a kingdom he has done nothing to make himself worthy of. Too many of his scenes felt tediously caricatured.

Thankfully, his nonstop seething is somewhat offset by the presence of a few good women– strong, aspirational, desirous. This is something we are increasingly seeing in socially conscientious films that are on the face of it set in very macho, male-dominated spaces. In such stories and settings, there is a special thrill attached to the idea of the outwardly demure, tradition-bound woman reducing a powerful man to jelly with a sharp word or gesture, or through sexual aggression. And while this can sometimes feel like tokenism (you might wonder if a film is erring on the side of being slyer and more progressive than the society it depicts), it also works very well when the actresses involved are of the quality of Dugal, Shweta Tripathi or Shriya Pilgaonkar.

Amid all the hurly-burly, their quieter scenes stand out – such as the one where Golu tersely asks her school principal to get to the point during a rambling conversation; or the one where Kaleen bhaiya’s dinner-table sermon to his son – “Yaad rakhna, aurat ki khushi hamesha aadmi se upar hoti hai” (“A woman’s pleasure should be above the man’s”) – is undercut by a barely audible snort from his wife who has never had an orgasm because he comes too soon.

These are the deflating little moments that Mirzapur could have had even more of, moments that free it from its burden of testosterone and masculine self-importance – much like the gun that explodes (prematurely) in the hands of its excited owner in one of those gory scenes.

I didn’t have high expectations of Mirzapur after watching the first 30 or so minutes. Everything seemed a little too on-the-nose, too underlined. Shortly after Munna beats someone up in a classroom, we see him making a vote-canvassing speech about how violence in classrooms won’t be tolerated (and two students exchange smiles). When an obsequious cop who is in the pay of a high-profile don arrives with bad news, we are promptly told he is just a “postman”. After a man tells his son “You are my family” and leaves the room, the son mutters to himself “Family hai issiliye toh virasat milne ka intezaar kar rahe hain” (“That’s why I am waiting for my inheritance”). The effect is that of over-expository conversations being held purely for our benefit, so we can quickly define characters and relationships.

In fairness, this could be because many people have to be introduced and established within the first few scenes. And things do get better: while the series never fully ditches the “tell, tell, tell” mode, it becomes more assured as it continues – and the starting point for this is a tense confrontation scene in the episode-one climax, which moves from ominous silences to an explosion of violence that somehow works despite a few cartoonish elements. With most of the central characters involved in the fight, it’s here that the narrative threads coalesce, all that exposition finally giving us a payoff.

And the scene ends with another of those poetically gruesome shots – drops of blood on the dining-table cutlery. Which brings us to an inevitable talking point: Mirzapur probably has more gore than any other Indian film or show you've seen recently.

Nor does it waste any time in telling the squeamish viewer to stay clear. Within the show’s first 10 minutes, a rowdy wedding celebration has ended with the groom (still on horseback) with a hole in his eye; another man has had his hand blown off; and a car tyre has squished a severed thumb lying on the road. In later episodes, brains are blown out with loving attention to detail; a man proves agonizingly hard to kill even when shot in the chest at point-blank range. Without giving away any details, the final act of the last episode provides a catalogue of murder, mutilation and psychological torture that will test even the most hardened nerves. And an old question rears its head: is this glut of violence 'necessary' to the film's purpose, or is it gratuitous – perhaps an enthusiastic overreaction to the greater freedoms that are (for the time being) available to web content in India?

The answer is probably somewhere in between. Watching Mirzapur, there were moments where I thought 'Well, did that face-exploding or innards-spilling shot have to be SO explicit for the point to be made?' (And I say this as someone who enjoys both gore and gratuitously amoral cinema if I feel it's well done.) This question is bolstered by the fact that the show sometimes marries brutality with slapstick, or has the soundtrack doing comedy while violence unfolds. In one cringe-making scene, while a boy is being kickedhard in the balls, his Accounts teacher, looking intoa textbook, mutters to himself: “Iss deal mein toh Sharma ki donon FD toot gayi.” (“Both of Sharma’s fixed deposits were broken.”)

The counter-argument might be that it's essential for this series to show us the thrill of violence, given its subject matter (Tripathi grows his business by encouraging people to use guns for both attack and defence) – and also given the trajectory of one of its most compelling characters, Guddu, a startling performance by Ali Fazal.

That Mirzapur is full of fine actors doing fine work should be no surprise to anyone who has watched these performers in indie or low-key films in recent years. Pankaj Tripathi has a well-earned reputation now (though he might soon be in danger of being over-used in a certain type of laconic, wry role), but there is also Vikrant Massey (who was outstanding as the gentle Shutu in A Death in the Gunj), Shweta Tripathi (who does bookish indifference very well here, as a girl named Golu who runs for the college elections) and Rasika Dugal, delicious as the frustrated wife who calls her stepson “Munna bhaiya” but perks up on hearing stories about his sexual stamina.

Given these riches (and I haven’t even mentioned the supporting cast), it feels like a child's game to pick a performance as the 'best', but Fazal was the pleasantest surprise for me. He is a revelation as the droopy-eyed,Big Moose-like oaf whose brain, we are told in an early scene, is as thick as the rest of his body. Whether he is drinking “ma ka doodh” from a baby’s bottle (while also taking supplements to buff up his body) or telling a girl – when she flirtatiously says she looks forward to seeing more of him than just his biceps – that he’ll invite her to the Mr Purvanchal contest in which he is participating, or simply cocking his head and hunching his shoulders, he is funny and endearing. Yet this is also what makes his transformation into someone who gets drunk on crime and power (“Shuru majboori mein kiye thay, ab majaa aa raha hai”) so troubling. Mirzapur’s most engaging narrative tracks by far are the ones involving Guddu and Bablu as they negotiate their new world and eventually face the consequences. Even as they transport blood-soaked carpets past the eyes of suspicious policemen, their story threatens to sweep the kaaleen out from under the viewer’s feet.

That Mirzapur is full of fine actors doing fine work should be no surprise to anyone who has watched these performers in indie or low-key films in recent years. Pankaj Tripathi has a well-earned reputation now (though he might soon be in danger of being over-used in a certain type of laconic, wry role) Agency picture

Rasika Dugal in a scene from Mirzapur The presence of a few good women– strong, aspirational, desirous -- frees Mirzapur from its burden of testosterone and masculine self-importance Agency picture

Munna (Divyendu Sharma), who is such a central character with so much screen time (the series both begins and ends with a close-up of his face), rarely moves beyond the gangster-film stereotype of the insecure, entitled, beast-like “prince” of a kingdom he has done nothing to make himself worthy of. Too many of his scenes felt tediously caricatured Agency picture