‘Layakari’. That’s something that family, friends, colleagues and comrades often hear from Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury. A word which, in many ways, is more of an emotion than one which can be justified by a descriptor; it comes closest to being in a state of happiness and peaceful co-existence. It is perhaps Roy Chowdhury’s version of the Japanese concept of ‘Ikigai’, meaning a motivating force which gives one a sense of fulfilment and purpose of living.

Roy Chowdhury — popular as Tony to almost everyone who knows him — derives his life force from the art and craft of filmmaking. Ever since his first film Anuranan — a relationship drama that included a stellar cast comprising Rahul Bose, Rituparna Sengupta, Rajat Kapoor and Raima Sen — that released 17 years ago, Tonyda has carved a niche for himself with his brand of filmmaking, constantly delivering meaningful cinema arising out of an out-of-the-box idea. His films ride on powerful and poignant themes, his pulse on both relevance and relationship being their distinctive differentiator.

“I believe in the power of relationships and the ability of cinema to make the viewer think. I believe in films having a healing power, both as an audience and as a filmmaker. Cinema, for me, is life,” says the extremely likeable Tonyda, as we chat in his tastefully done-up home in South Calcutta.

At his “second home”, The Tollygunge Club

Popular in his circle, and even outside it, the man has always let his work do his talking. He has remained behind the scenes, allowing his films and his cast and crew to take their rightful spot in the limelight.

FORCE BEHIND HIS FILMS

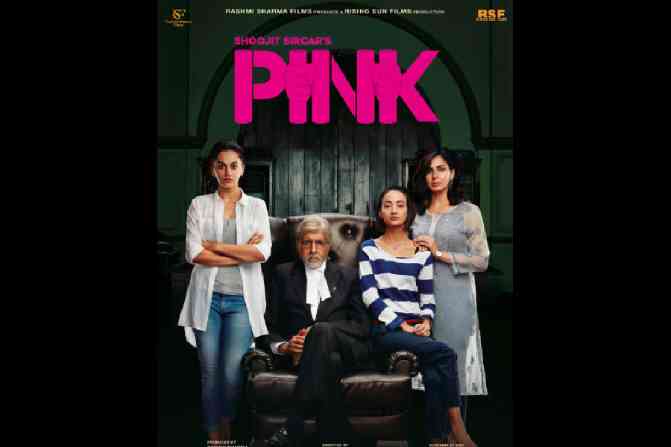

This was even when his Hindi debut Pink became a global phenomenon. Released in 2016, the film trained its lens on the casual as well as practised sexism that women are made to face and the unjustified ‘rulebook’ of right and wrong that society expects them to live by. The curiously titled Pink, which the director initially planned as a Bangla film, became a movement within a very short time, striking a chord with women and men alike. The film made a star out of Taapsee Pannu, gave a fillip to the careers of Vijay Varma, Kirti Kulhari and Angad Bedi and once again reinforced the power of Amitabh Bachchan’s acting. Its succinctly coined ‘No means no’ has organically made its way into our vocabulary.

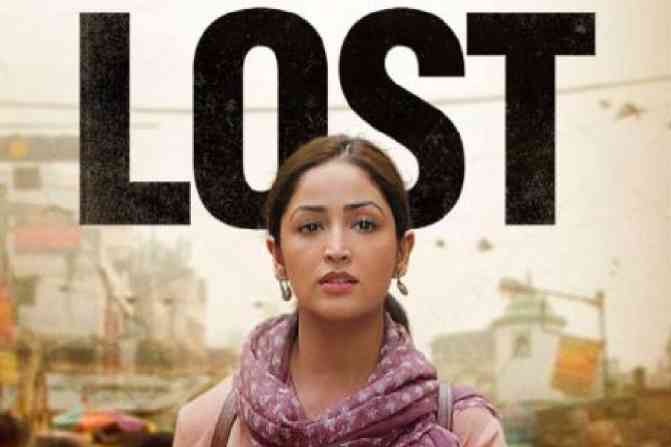

But Tonyda has never been in a hurry to cash in on success. His second Hindi film Lost, headlined by a career-defining act from Yami Gautam Dhar, released earlier this year, almost seven years after Pink. Movie-making for him, as he repeats often and lives by, has never been a money-making exercise. “I am not in any sort of competition. A film can’t be number 1,2 or 3. A film can just be a film,” he says. “I cannot make films very frequently. Ideas have to marinate in my head, a film has to grow and live within me,” he says.

HIS CINEMA, HIS LIFE

Almost all of Tonyda’s films have stemmed from his life experiences or derived their seed from his keen powers of observation. Antaheen, his second feature film starring Rahul Bose and a then relatively little-known Radhika Apte — a poignant human drama on two strangers connecting virtually — came from the director’s own email conversations with a female friend living abroad.

Pink was his response to the anger he felt at women being judged and derided by society. “My house in Lake Gardens had a tea stall below it where a lot of girls from the North-East would come, dressed in short clothes. They were inhibition-less and so beautiful and carefree. I would see how even educated people would judge them. I have seen a woman living alone in an apartment being judged when she would bring her male friends home for a drink. Who is anyone to judge what is wrong or right?” he asks, his anger still palpable, making Roy Chowdhury one of those dying breed of filmmakers whose investment in making a statement and bringing about change through cinema dominates over their desire to make money and chase after fame.

His early 2023 release Lost, starring Yami Gautam Dhar

Anyone who knows Tonyda will be aware of the fact that he loves telling a good story, even beyond the frame of 70mm. He talks about how Dev’s character — an immigrant who turns into a smuggler — in his 2014 film Buno Haansh came from his own life. “I was an avid film buff and many decades ago, I wanted to buy a VCR but I didn’t have the money. I was asked to carry a bag in return for a lakh of rupees, but if I was caught, I was told that I could face three years in jail,” he says. The desire to own a VCR had to wait, but Roy Chowdhury’s dream of making films was on its way pretty early on in life.

THE POWER OF IMAGES

“The power of images — both moving and otherwise — impacted me at a very young age,” he says. Anuranan was born out of an image of moonlight hitting a mountain while on a holiday in the hills, but Tonyda’s fascination for cinema had started much before that.

“Since childhood, I used to watch a lot of films... Hindi, Bangla and English. I also watched a lot of films which I was not even supposed to watch!” he laughs.

“We had the culture of movie-watching in the family. About 25-30 people in the family would go together to the theatre and watch films. There was a leaning towards watching films by Tapan Sinha, Tarun Majumdar, Satyajit Ray, films starring Uttam Kumar...” he continues.

Films of all kinds had a profound effect on him as a youngster growing up in Baranagar. “I would be intrigued by every aspect of a film, from the performances to the direction, from lighting to camera work. I would always read between the lines. I was taken in by the visual capability of a film to draw in a viewer.”

While Francois Truffaut and Ingmar Bergman had a huge impact on young Tony, he was also deeply affected by the power of music. “Classical music has always been a big part of my life. I always wanted to play a musical instrument. From class X, I would watch almost every classical music programme that would take place in the city. Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan-er programmes ey just dhuke jetam. My close friend Tonmoy Bose would give me tickets,” he says. “I would listen to a Sarod recital on my cassette player, I would listen to Kishore Kumar... I was drawn to everything.”

The fact that images form a big part of the filmmaker’s creative scape is evident by the space he inhabits. The walls of his home are adorned by paintings, each handpicked by him or gifted by those who appreciate his understanding of art. His conversations with friends revolve around film and music and most often about food.

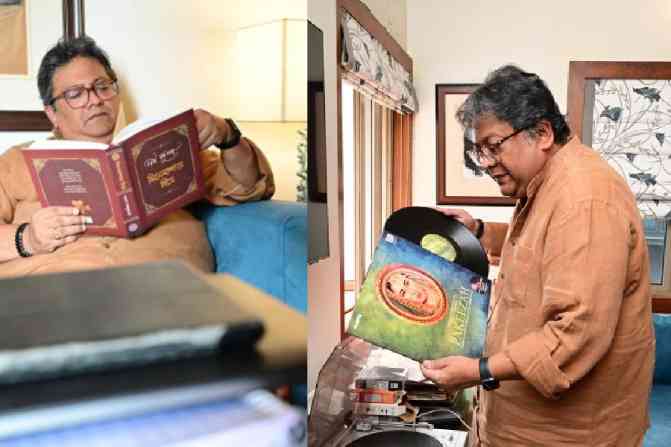

His den in his Calcutta home — as well as his pad in Mumbai — is full of books spanning a variety of subjects. Occupying pride of place is a record player and a collection of carefully collected vinyl records. Tonyda sits here every day, ruminating, writing, looking out of the window, reading a book or listening to music.

His state of Ikigai — brought on by what he claims is a life which is contented but not burdened by unnecessary demands — may be enviable today, but Roy Chowdhury didn’t have a smooth journey towards realising his dream.“My father was in the construction business. I stayed in Paschim Putiary and there were a lot of people involved in working in films living there, who struggled on a daily basis. My father saw all that and, of course, he was apprehensive about me joining this career. Money was important even then, at least to lead a comfortable life.

I actually worked in my father’s business for a few years. I have lived on the streets of Bhagalpur in a tent,” he smiles.

But even while he was working in a field which directly clashed with his ambitions, Roy Chowdhury never let the magic of cinema leave him. “While working in Bihar, I once walked to a stream where the light of the moon was falling on the water. I sat and stared at that sight the whole night. I don’t even remember now whether it was for real or a dream,” he smiles.

“I have dealt with notorious people. I have seen rifles. I have seen both gun and gaan culture... I have seen life. And all of that has contributed to the storyteller in me. I have interacted very simply, at the grassroots level, with simple, ordinary people,” he says.

He even worked as a salesman, selling room fresheners from door to door, but always keeping his antenna up in search of a story. “I would go from house to house and just speak to people. I have collected the life stories of so many people, I would always lend a patient ear even to strangers. I would manage to sell more than my target. An old lady didn’t have anyone to speak to. She would make omelette and bread for me and we would speak for hours. I believe that talking to people heals me,” says Tonyda.

THE FIRST STEP

He then stepped into the world of advertising which gave him his first shot at telling stories, though in a truncated medium. “I made a telefilm called Stepping Out Stranger for Doordarshan in the ’80s. I realised I could tell stories. But there was no money and I joined advertising. Advertising was doing well in Calcutta then. I did a lot of ads for Coke, Nestle and other brands. I started making four to five ad films a month,” smiles the man.

Rahul Bose and Raima Sen in Anuranan

Advertising — he has made 700-800 ad films so far — was the stepping stone to films. “Advertising gave me the platform to learn. Constant learning is very important in filmmaking. Film has to be learnt, it can’t be taught.”

Roy Chowdhury won a National Award on debut for Anuranan, but swimming against the tide in terms of idea and execution meant that he always had naysayers. “When I said I wanted to make Anuranan, people asked me: ‘Montage-r upor film banabe?’” In the case of Antaheen, no one thought that a film with two people interacting on the computer could engage an audience for two hours. Even when I took the story of Pink to many people, they asked: ‘Botal sar pe tod diya toh kya hua? Where is the conflict?’ But I stuck to what I believe in,” he says.

AWARDS AND APPRECIATION

The filmmaker’s belief in himself and his ideas has paid off rich dividends, even when some of his films haven’t worked commercially. “I don’t look at the result. I simply enjoy the process.” His films have won seven to eight National Awards, besides a host of other accolades. He also counts as special the prestigious Aravindan Puraskaram from Kerala for Anuranan, given to a debutant director and named after after filmmaker G. Aravindan.

His much-lauded Hindi debut Pink, led by Amitabh Bachchan

The appreciation and love from the audience have been no less. “After Pink, a lady came to my doorstep and asked me to give her Ankit’s (played by Vijay Varma) number because she wanted to hit him. A few months ago, I met Vijay at IIFA and he told me: ‘Tonyda, you started all this’ (his successful spell of negative roles).” He continues: “At a party in Mumbai, two young girls came up to me and gave me a tight hug and said: ‘Thank you for making Pink’.”

For the first time, Roy Chowdhury — who is poised to make a Bangla as well as a Hindi film next — has two films coming out in the same calendar year. Lost came out in February and his next Hindi film Kadak Singh — comprising the enviable cast of Pankaj Tripathi, Parvathy, Jaya Ahsan and Sanjana Sanghi — will stream soon on Zee5. However, the filmmaker believes that this is more of an aberration than a rule going forward.

“Every film is like a baby to me. I have to keep making films, irrespective of their fate. I take my own time. I don’t want to become a victim of the market. I don’t have the ambition to make 50 films,” he says. He cites one of his favourite dialogues from Manmohan Desai’s Amar Akbar Anthony as an illustration of how he approaches his work. In the film, Anthony (Amitabh Bachchan) tells Amar (Vinod Khanna): ‘Tumne mujhe bahut maara. Maine tumhein sirf do maara, lekin solid tha na?’ That’s what I also believe in life... less is more,” smiles Tonyda.

He says this as we are seated at The Tollygunge Club, which, over the years has become an indelible part of him as a person and his DNA as a filmmaker. “This is my second home. I actually live between Bombay and Tolly Club,” he smiles, digging into the club’s signature Chicken Roast on his ‘cheat day’. He wants to direct a Malayalam film one day, he tells us, talking about the kind of profound effect the cinema from that state has had on him. “It may take some time, but I will definitely do it,” he says determinedly, in between mouthfuls. It is at that moment that I take his leave, letting that idea “marinate” within him.