One of the most profound and nuanced explorations of caste discrimination and social

inequality in Indian cinema, Sujata directed by Bimal Roy, was adapted from Subodh Ghosh’s short story.

It tells the story of a young woman born into the Dalit community but raised by a Brahmin couple, Upen and Charu, played by Tarun Bose and Sulochana, respectively. Despite being loved and nurtured by her adoptive father, Sujata’s status as an untouchable remains an unspoken barrier between her and her adoptive mother, Charu, as well as her foster sister, Rama, a role essayed by Shashikala. The plot thickens when Sujata falls in love with Sunil Dutt’s Adheer, a well-educated young man from an upper-caste family, which forces the issue of her untouchable status to the forefront once again.

Set against the backdrop of post-Independence India, Sujata addresses the persistent realities of the caste system, despite the country’s growing movement towards modernity and equality. Bimal Roy, known for his socially conscious films such as Do Bigha Zamin and Biraj Bahu, uses Sujata to critique the hypocrisy of a society that clings to archaic notions of purity and pollution, even as it espouses democracy and progress.

The film’s emotional core lies in Sujata’s relationships with her foster family. Upen’s unconditional love for Sujata contrasts sharply with Charu’s internalised caste prejudices. Tarun Bose delivers a restrained yet powerful performance as Upen, embodying a progressive ideal that transcends societal norms. Sulochana’s portrayal of Charu captures the conflict of a woman torn between societal expectations and maternal instincts.

Her struggle is palpable, particularly in moments where she hesitates to embrace Sujata fully, despite her deep-seated affection for the girl.

Shashikala’s Rama, though secondary to the main plot, serves as a foil to Sujata. Rama’s carefree and privileged life as a Brahmin girl highlights the unjust differences in their upbringing, despite being raised in the same household. Rama’s eventual acceptance of Sujata symbolises the potential for change and the breaking down of caste barriers among the younger generation.

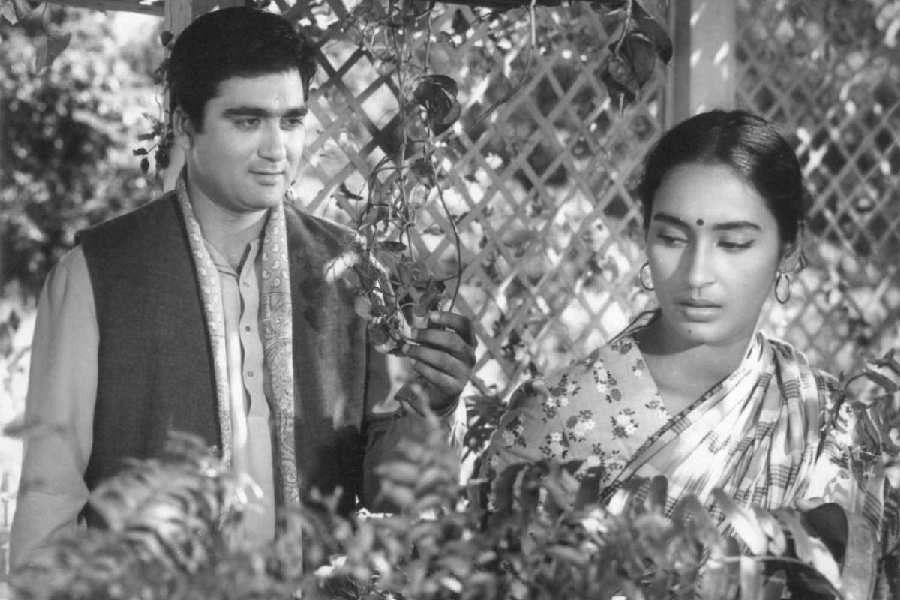

The relationship between Sujata and Adheer is central to the narrative, serving as a microcosm of a larger societal conflict.

Adheer is progressive, embodying the educated modern man who values human qualities over caste identities. Their love story is not just romantic; it is a radical assertion of equality and an open challenge to the caste system. However, their relationship also brings to light deep-seated prejudices, which continue to plague even those who consider themselves enlightened.

Nutan’s portrayal of Sujata is the film’s highlight. Her ability to convey Sujata’s inner turmoil through subtle expressions and restrained body language is a testament to her extraordinary talent.

The complexity of Sujata’s character is evident in her conflicting emotions — her deep love for her adoptive parents, her desire to be accepted, and her awareness of the societal stigma attached to her birth. Nutan navigates these emotions with grace, ensuring that Sujata remains a relatable and empathetic figure.

One of the most poignant scenes is when Sujata overhears a conversation about her untouchable status. Nutan’s silent yet powerful reaction in this scene encapsulates the pain of a lifetime spent on the fringes of society, despite being brought up in a loving home.

Roy’s direction in Sujata is marked by his characteristic realism and deep humanism. He uses simple yet effective cinematic techniques to heighten the film’s emotional impact. The use of close-ups, particularly of Nutan, captures the nuanced expressions that define Sujata’s character. Roy’s decision to avoid melodrama, even in moments of high emotional tension, allows the film to maintain its dignity and realism.

Roy also uses symbolism effectively throughout the film. The recurring motif of water — whether it is Sujata pouring water, washing or standing by the river — serves as a metaphor for purity and the fluidity of identity, challenging the rigid boundaries of caste. The subtle use of lighting and shadow further enhances the film’s thematic depth, with Sujata often shown in soft, diffused light, emphasising her innocence and inner purity.

The music of Sujata, composed by S.D. Burman, is integral to the film’s narrative and emotional resonance. The songs are not mere interludes but serve as extensions of the characters’ inner worlds. Tum Jiyo Hazaaron Saal, sung by Geeta Dutt, is both a lullaby and a poignant expression of Charu’s conflicted love for Sujata. Kaali Ghata Chhaye reflects Sujata’s longing and the storm of emotions brewing within her as she grapples with her identity and societal rejection.

The evergreen Jalte Hain Jiske Liye, sung by Talat Mahmood, is one of the most hauntingly beautiful songs in Hindi cinema. It encapsulates the unspoken love and yearning between Sujata and Adheer, and its melancholic melody mirrors the uncertainty of their relationship, burdened by societal expectations. Burman’s music, combined with poignant lyrics by Majrooh Sultanpuri, complements the film’s narrative, enhancing its emotional depth and timeless appeal.

Sujata remains a significant work in Roy’s filmography and in Indian cinema as a whole. Its exploration of caste and social discrimination is both sensitive and incisive. The film’s success lies in its ability to humanise the issue, making it not just a story about untouchability but about the universal desire for love, acceptance and dignity.

The film also holds an important place in the history of Indian cinema for its progressive portrayal of women and marginalised communities. Sujata’s character is a rare example of a strong, independent woman in Indian films of that era — someone who, despite her circumstances, retains her self-respect and moral integrity.

The film’s ending, which suggests a breaking away from traditional caste norms, was revolutionary for its time, offering a vision of hope and social reform.