Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.” That’s the first sentence of Little Women, and I’m happy to say that in the just-ended gloomy holiday season — when so much of humanity has earned Krampus or coal — the new movie version of Louisa May Alcott’s novel comes as an absolute gift.

A whole stocking full, really. Written and directed by Greta Gerwig, this Little Women — the latest of many adaptations — embraces its source material with eager enthusiasm rather than timid reverence. It is faithful enough to satisfy the book’s passionate devotees, who will recognise the work of a kindred spirit, while standing on its own as an independent and inventive piece of contemporary popular culture. Without resorting to self-conscious anachronism or fussy antiquarianism, Gerwig has fashioned a story that feels at once entirely true to its 19th-century origins and utterly modern.

Some of that freshness comes from the cast, a cornucopia of effervescent young talent ballasted by a handful of doughty old-timers. There is also an exuberance — an appetite for clothes, books, baked goods and adventure — that effortlessly links then to now. At the centre of the hullabaloo, as she was in Gerwig’s Lady Bird, is Saoirse Ronan. She plays Jo March, the second oldest of four sisters living in Concord, Mass., during and after the Civil War.

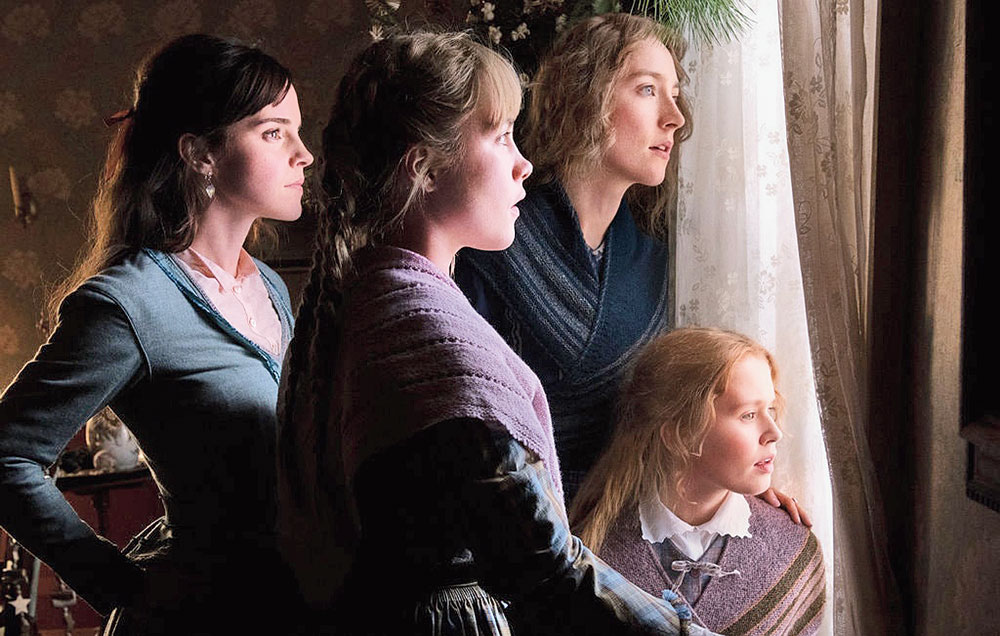

The foursome varies by temperament and talent, inviting a mix-and-match game of identification and infatuation. The oldest, Meg (Emma Watson) is theatrical and responsible; Beth (Eliza Scanlen) is musical and sweet. The youngest sister, Amy (Florence Pugh), and Jo are a painter and a writer who are frequently at odds. Before romance, tragedy and the ordinary pains of growing up complicate matters, they are an inseparable if not always harmonious troupe. Jo writes the plays that the rest of them perform for an audience that includes various toys, their mother (Laura Dern) and Hannah (Jayne Houdyshell), the housekeeper.

But the sisters live mainly to delight (and sometimes to torment) one another. The spectacle of their natural, affectionate, clamourous intimacy is a joy to behold, one we occasionally glimpse through the amused eyes of potential suitors, fond neighbours and a prodigiously judgmental and very wealthy aunt played by Meryl Streep. The girls’ nonjudgmental, non-wealthy father is played by Bob Odenkirk.

Rather than starting where Alcott does, during an austere wartime Christmas, Gerwig introduces us to Jo seven years later, an ink-stained scribbler paying a visit to a New York publisher (Tracy Letts). The rest of Little Women zigzags between two periods in the lives of Jo and her family. Whereas Alcott traces their fates in a straight line, Gerwig (aided by the deft editing of Nick Houy and the musical stitching of Alexandre Desplat’s score) proceeds by association and recollection. It’s as if the book has been carefully cut apart and reassembled, its signatures sewn back together in an order that produces sparks of surprise and occasional bouts of pleasurable dizziness.

This chronological shuffling jolts the story awake and nudges the viewer to pay close attention. Like any good novelist and every great filmmaker, Gerwig isn’t afraid to let her audience work a little. She trusts our intelligence and our curiosity, and also her own command of the medium. Reshuffling the plot is a way of making Little Women more cinematic without resorting to tricks or gimmicks.

As much as The Irishman or Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, this is a film that tackles the mysteries of time. In Gerwig’s hands, the specific magic of the medium — its ability to reorder the sequence of events, to slow down and speed up, to project memory ahead of experience — becomes a tool of philosophical and emotional inquiry. We observe the March sisters becoming who we have always known them to be, and also figuring out, for themselves, who they are.

Their simultaneous comings-of-age take place amid the constraints and opportunities of their time, place, class and gender. The publisher who buys Jo’s sensational tales instructs her that women in fiction must wind up either married or dead, and Little Women the movie obeys that imperative, though not in quite the same way that Little Women the novel does. Romance arrives in the person of young Teddy Laurence (Timothee Chalamet), the slightly dissolute grandson of a wealthy Concord widower (Chris Cooper). Laurie, as the sisters call him, seems at times more like a fifth March sister or an untrained puppy than like boyfriend material. He can’t even sit properly in a chair!

Meg, by consensus the prettiest of the four, falls for Laurie’s tutor (James Norton), which means that her wedding vow is also a vow of poverty. The more practical-minded Amy, counselled by Aunt March, grasps the economic implications of marriage. Jo, who catches the eye of both Laurie and a certain Professor Bhaer (Louis Garrel), might prefer not to marry at all. The question of freedom — in particular of a woman’s independence in a society that is both liberal and governed by tradition — is threaded through nearly every scene.

“I’ve been angry every day of my life,” Mrs March says matter-of-factly, and while Little Women is full of silliness and sorrow, sweetness and warmth, it doesn’t minimise or apologise for that anger. Nor does it mock or marginalise the March family’s commitment to social justice, civic responsibility and artistic excellence. All of those were, for Alcott, part of the mainstream of American culture. Gerwig knows that they still are.

And so is this kind of entertainment: generous, sincere, full of critical intelligence and honest sentiment, self-aware without the slightest hint of cynicism, grounded in the particulars of life and accessible to everyone. Don’t let the diminutive title fool you. Little Women is major. It seems fitting to finish with Alcott’s last sentence: “I can never wish you a greater happiness than this!”