The subdued interiors of a shop in filmmaker Faraz Ali’s short film Obur (Cloud) are a cold mixture of shadows and icy colours. In command of his craft, he injects an eerie tension as a teenage boy is on the verge of losing his memories of his ailing mother. He pawns off his iPhone to a pharmacist in exchange for his mother’s medical aid.

As the films — the other three being Archana Atul Phadke’s Mirage, Saumyananda Sahi’s A New Life and Prateek Vats’s Jal Tu Jalaal Tu — unrolled on the big screen in Mumbai, viewers felt that the filmmakers had complete confidence in their material, their performers and their camera, which has turned out to be the iPhone 15 Pro Max.

In another short film, Crossing Borders, Saurav Rai’s camera ping-pongs between a woman, who smuggles simple everyday items like saris and umbrellas across the Indo-Nepalese border, and two children, besides the picturesque mountains of Darjeeling. His camera often builds intensity in scenes by maintaining some distance.

Be it actors facing each other across a small room, a close-up or scenes packed with fast movements, the audience became witness to a new fertile period in filmmaking, one that involves making diverse titles using the iPhone.

(Left to right) Vishal Bhardwaj, Rohan Sippy and Vikramaditya Motwane at the screen of the films selected for the 2024 MAMI Select — Filmed on iPhone programme

The five filmmakers were selected by the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) to create short films for the 2024 MAMI Select — Filmed on iPhone programme. Mentoring them were industry icons Vikramaditya Motwane, Rohan Sippy and Vishal Bhardwaj.

‘Completely changes the psychology’

“All of us are familiar with this camera,” said Sippy, pointing at an iPhone. “When a film camera is used, you might get conscious but somehow this is now part of our landscape. So I think that really is something that helps them. You don’t come with the convention of 100 people sitting on the other side of an actor, which is how we approach filmmaking. But if it’s just a couple of people there, and it’s (the iPhone) something that actors are used to… they probably would post on Instagram or whatever and they are used to shooting videos of themselves… that completely changes the psychology and allows for a whole new way of getting other kinds of faces and talents on the screen.”

Rohan Sippy, the director behind a number of Bollywood classics, mentored Faraz Ali and Saurav Rai while Vikramaditya Motwane mentored Archana Atul Phadke and Saumyananda Sahi. As for Vishal Bhardwaj, he mentored Prateek Vats.

The five filmmakers used the iPhone 15 Pro Max to shoot their films and they also used MacBook Pro with the M3 Max chip, allowing them to edit in even the most remote locations under varying climatic zones.

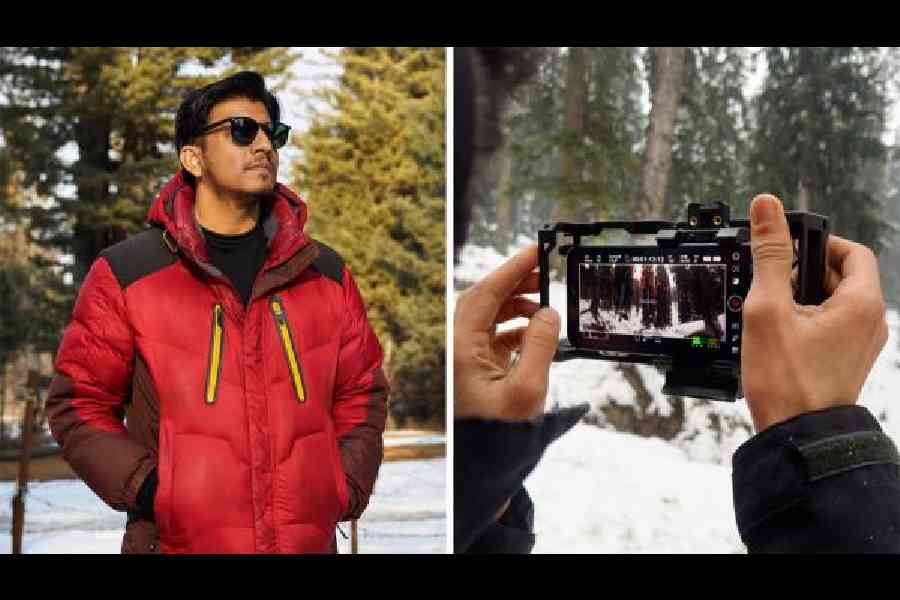

Picture left: Working with mentor Rohan Sippy (left), Saurav Rai let hyperreality define his style and prioritised simplicity in his process. Picture right: Rai (centre) sets up a shot on iPhone 15 Pro Max

Even though the directors were working with what appeared to be “unconventional” cameras at the moment, it didn’t change their approach, at least it didn’t for Faraz.

“I personally didn’t want to change the process; I wanted to treat the process of shooting on the iPhone to be as complicated, as beautiful, as simplified as I treat rest of the technology that we use. Unless and until I believe in it, I won’t be able to pull it off. And there’s always a first time. There was the Lumiere brothers who believed in it. One thing about cinema is that it comes from curiosity. Unless we take the camera and think what if it all starts with a what-if. So I felt that it needed the what-if, it needed the curiosity, the same amount of curiosity that we have by holding a bigger-format camera,” said the director of Obur (Cloud).

He said that he was excited about the level of naturalism and realism the iPhone offers. “The moment we would take a bigger camera and put it in front of people, they will get intimidated. They’ll never be their natural self. Away from the camera, they’ll be speaking in a different body language. The moment you put in the camera, they’ll feel like there is histrionics to cinema. So they’ll speak in a certain vocabulary, they’ll be like… it has to be dialogue-ish and it will be very caricature-ish. The moment there was a phone, they were more of themselves, they were more comfortable, they thought that the stakes were low. And I feel that in cinema it can be opulent what you are shooting, but the process should feel like the stakes are low, the more you can camouflage, at least for the stories that we wanted to tell, the better it is, so hence this compact technology packed with producing 4K, shooting it on ProRes Log and all the good stuff the iPhone does. I think the biggest thing is it can help our actors perform and be themselves without being so intimidated.”

Obur captures a snowy Kashmir where colours wait their turn to take centre stage. The tragicomedy follows a teenage boy who goes to extremes to make his ailing mother feel comfortable, even if that meant trading in his beloved iPhone at the pharmacist to buy a medical aid, which ultimately she gets to appreciate for a few minutes only. Silently playing in the backdrop are developments in Kashmir that we read in newspapers every other day, like electricity problems and the Internet being — for the lack of a better word — wobbly.

Saurav Rai agrees with Faraz and takes the point forward. “The ease with which my team and I could move around is important. Traditionally, we have to do a lot of gear-shifting between scenes. With the iPhone it’s different and fantastic,” said the man whose debut film, Gudh (Nest), was an official selection at the 69th Cannes Film Festival in 2016.

In Crossing Borders, he was inspired by his aunt to tell the story of a woman who smuggles goods across the Indo-Nepalese border. On the way, she meets two children who also need to travel across the border and in the process themes of immigration and identity get explored. The smartphone helped simplify the shooting process. He shot on the iPhone 15 Pro Max and then came colour correction. “No fuss, no gimmicks.”

Archana Atul Phadke worked with cinematographer Amith Surendran, using the 120mm 5x telephoto camera of iPhone 15 Pro Max to add depth to the vast desert landscape setting

All sides to clouds

There is a high degree of viewer connectivity to each of the plots. Take the case of Obur and the idea behind storing data in the Cloud.

“For the longest time I was sitting with the idea of memories that we have. In the times we live in, memories often become data. I wanted to understand the data that we refer to and how we archive it on the Cloud, what happens if we lose it or what happens if it comes under a threat. Is it a luxury which is only exposed to certain people who can either afford it or have access to it living in cities? What happens to a person living in the village, who has backed up his data on the Cloud, and then there is no Internet or low Internet? Would he or she have access to the most precious memory that person has stored?” said Faraz.

Picture left: Filmmaker Prateek Vats (right) worked with mentor Vishal Bhardwaj. Picture right: Vats (foreground centre) shooting his film Jal Tu Jalal Tu

It’s exactly what happens to the young protagonist in Obur. After his mother dies, all he needs is a photograph of her and given the times we live in, all our memories are stored on the phone and the Cloud. It’s a thought we want to run away from but that’s Truth with a capital ’T’.

In the film there is a conflict. “And since there is a conflict, there is a story to tell.” And he chose a backdrop that’s beautiful but, at the same time, life can be harsh here. “Mounting the film against the backdrop of Kashmir, I saw so much of innocence in people and also there’s enough written about Kashmir and we have been feeling a certain way. I wanted to attempt a tragicomedy. I wanted the audience to laugh about it and have something really light as a subject to be explored in that milieu rather than saying something heavy about that place. Then everything fell into place, the moment clouds were in place and the harsh weather supported the story. We were able to execute the subject using the iPhone and in the milieu that we thought would work.”

Saurav Rai had his aunt on his mind while working on Crossing Borders. “I think for the longest time the concept of the film had been with me. It started from thinking about a distant aunt. I used to hear about her many experiences, some funny anecdotes. Working along the border and in certain terrains, it’s difficult to take big equipment. So having the iPhone was just perfect and it helped bring out the many dimensions to the characters you see in the film.”

Tricks and treats with the iPhone

For Archana Atul Phadke, a young boy outside Jaisalmer gets the windmills of our minds turning. Titled Mirage, the film captures the life of a boy who spends most of his time on the iPhone, playing a game. But then he loses the phone (and his peace) to the desert. Each time he taps the shoot icon on his video game, our minds are triggered and that’s the power of sound while the empty desert landscape “makes people conscious about the fact that they’re breathing”.

The iPhone 15 Pro Max has allowed her to experiment with her visual storytelling skills. “With the default 24mm main camera, I explore wide shots in the beginning. Towards the end, the 120mm telephoto camera — which gives amazing depth — makes the boy’s world smaller and smaller,” she said. In fact, the final shot in her film offered a jolt strong enough to shake up buckets of popcorn in the movie theatre.

In the desert, she could handle the shoot with a completely wireless ecosystem: The Apple Watch was used to operate and monitor the iPhone camera, while an iPad served as a larger monitor, and AirPods allowed her to check the sound before she slipped into editing on her MacBook Pro with M3 Max.

In A New Life, the story plays out via video calls. “We’re shooting the video calls in real time, and iPhone is a part of the performances,” says Sahi

Saumyananda Sahi — the cinematographer behind the BAFTA and Academy Award-nominated documentary All That Breathes — is behind the camera on A New Life, which seamlessly shifts the action between Calcutta and Bangalore. A migrant factory worker is in Bangalore looking for a job while his pregnant wife has to accept the pitfalls of a long-distance relationship.

For him, the iPhone has turned out to be a wonderful camera. “I can peg exposure or shoot Log like I usually do on an Arri Alexa cinema camera. It’s amazing that iPhone 15 Pro Max can live up to all that,” said the director who at a young age fell in love with the films of Ingmar Bergman and Andrei Tarkovsky, and later trained at Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) where he met Tanushree Das, his future wife and co-director of A New Life.

Director Prateek Vats has been inspired by Anton Chekhov’s short story, The Death of a Government Clerk to shoot Jal Tu Jalaal Tu (You Are Water, You Are the All-Powerful). The layered plot captures the anxiety of a middle-aged factory worker who accidentally offends his employer by laughing at the wrong moment but it sets off a chain of reactions which moves from pleading for forgiveness to thinking why he needed forgiveness.

Set in a real garment factory in Sonipat, the iPhone 15 Pro Max helped Prateek and his co-director Shubham to capture the colours of the factory. The latest iPhone Pro models allow filming in Pro Res Log, marking a landmark shift in how films are shot on the smartphone. Footage captured in this format can be edited however a filmmaker wants, allowing them to precisely tune specific areas in terms of exposure and colour. The director shot the film in a 4:3 aspect ratio, taking viewers back to TV sets from the 1990s.

“When anyone with a vision — irrespective of their background — is empowered to make films, the storytelling potential of this country will really blossom,” he said.

Pushing the iPhone

Since Sean Baker filmed Tangerine on the iPhone in 2015, the device has come a very long way. In fact, techies have been left amazed by the level of innovation the iPhone has given the world since 2007. What has changed drastically is the number of genres the iPhone can take on, even if it involves a good deal of fast movements, like we saw on Vishal Bhardwaj’s Fursat last year.

From left to right: Filmmaker Faraz Ali believes that iPhone 15 Pro Max lets him go where filmmakers with bigger cameras cannot — like the snowy white peaks of Kashmir. Cinematographer Anand Bansal used ProRes video with Log encoding to enable range and flexibility for the postproduction of Obur

Rohan Sippy agrees. The veteran filmmaker tells t2: “The acid test is putting up (the footage) on the big screen and it has flawlessly passed that test as well. The technical challenge of shooting snow is difficult. Shooting the level of blacks that Archana’s film has is also a challenge… holding on to highlights… all the technical details that cinematographers have been talking to me about for around 35 years. And suddenly you see that you can still achieve a palette that is very pleasing and it also just disappears and lets you get immersed in the story. Whatever you’re trying to do in terms of art, direction, lighting, all of that you can do the way you would with the conventional stuff. But you’re doing it now with a tool that we are just about starting to understand and wondering how far we can push it.”

Faraz has been encouraged by the level of tech prowess the iPhone has to offer. “The encouragement comes from technology as well as the portability of it. So definitely it’s a tool that did justice to the five films you saw. The narratives are fictional. But I’m (also) saying that imagine this as a tool being used for non-fiction, for documentaries, imagine where all the small places this (the iPhone) can navigate, and we are shooting in 4K. The future is here, so there will be so many beautiful documentaries that we are all going to witness being shot on the iPhone. I think we have just managed to scratch the surface.”

Of course, it was Sippy who said it best: “Technology just opens up the imagination and boundaries simply disappear.”