With her fiction feature debut, Payal Kapadia has travelled a path which no other Indian filmmaker has set foot on before. All We Imagine As Light — a richly observed inter-generational story of female empowerment in modern-day Mumbai, which is both melancholic and magical and hypnotic in many ways — won Kapadia, 38, the prestigious Grand Prix at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, the festival’s second-biggest prize.

Even before that, All We Imagine As Light had scripted history, becoming the first Indian film in 30 years to be screened in the Main Competition section at Cannes.

Kapadia is no stranger to Cannes glory. In 2017, her short film Afternoon Clouds was the only Indian film selected for the 70th Cannes Film Festival. In 2021, she won the Golden Eye award for best documentary film at the 74th edition of the festival for her debut feature A Night of Knowing Nothing.

However, it is All We Imagine As Light that has placed the filmmaker firmly in the international spotlight. Warmly received by audiences across the world and receiving unanimously positive reviews, the film — a co-production between companies from France, India, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Italy — was shot in Mumbai and Ratnagiri over a period of 40 days, and stands out for its theme, tone and treatment.

After inviting a fair bit of chatter for not being selected as India’s entry to the Academy Awards, to be held in March, All We Imagine As Light is now set to release in Indian cinemas on November 22. t2oS caught up with Kapadia, an alumnus of the Film and Television Institute of India, on the art and craft of her film, her love for Calcutta and more.

Over the last few months, with each accolade that All We Imagine As Light has received, you must have experienced a wide range of emotions. As the film nears its India release date on November 22, what is your dominant state of mind?

I keep saying that I am very happy. But then my mother called me a few days ago and said: ‘You are saying you are happy in too many interviews. You can’t say you are happy all the time!’ (Laughs) I told her: ‘But I am feeling happy! What else do I say?!’

Honestly, for me, it is always a feeling of discovery when the film is shown in a place where I haven’t been before. For example, we were in Ernakulam two days ago. A young girl saw the film and the kind of reflections she made about the story included a lot of things that I had thought about in the script but it was kind of subtle and not everybody was picking it up. But she got it in one watch. That really was a big high. It is nice to see the audience responding to All We Imagine As Light from so many perspectives.

When we showed the film in France, a viewer of Indian origin came up to me and said: ‘This is like my life. But how did you know about it?!’ Over the years, I had read interviews of filmmakers where they had cited instances of audience members telling them how much a film or a character reflected their lives. I always wondered what that would feel like. When that happened to me, it was a beautiful moment. I mean it is not so nice in a way because the film has a pretty sad story (smiles). But to just get that kind of a feeling as a filmmaker was special.

The film, of course, is very much Mumbai in look, feel and DNA, and yet it has connected deeply with audiences across the world. What do you think works in terms of the universality of the story?

There are some very fundamental things in the film, whether it is about loneliness or friendship or big-city life. These are universal themes, especially for people who have moved out of home, are living somewhere else, have forged new friendships in those places but have also felt alone. I think those are the universal themes that people do pick up, even though the kind of story that Prabha (played by Kani Kusruti) has, for example, will make many viewers outside India sometimes say: ‘Oh, why can’t she leave her husband?’ And I have to explain that things like these are more complicated in our country... most find it difficult to just get up and leave... that it is more of a societal and cultural thing here.

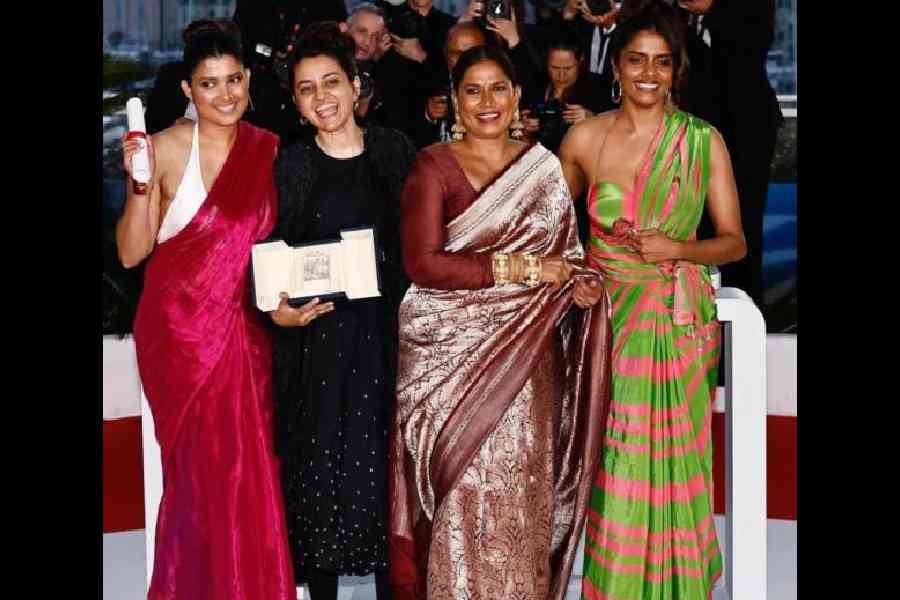

Payal Kapadia (in black) with Divya Prabha, Chhaya Kadam and Kani Kusruti after winning the Grand Prix for All We Imagine As Light at the Cannes Film Festival in May

But fundamentally, the themes are quite universal and they affect all people, no matter what perspective they are coming from.

Was there a moment of epiphany that made you want to make All We Imagine As Light?

I was quite clear from the beginning what I wanted in this film and intergenerational friendship was certainly one of them. It was something that I had been thinking about for a long time, because I am always surrounded by women of different ages. I am also growing older. And as I am doing so, I am reflecting a lot on how I respond to women who are older than me and also younger than I am. This question of intergenerational camaraderie has always been on my mind.

Somehow those questions, those themes always come into your film, no matter what story you have. I also wanted to explore loneliness. Even my short film (Afternoon Clouds, the only Indian film selected in competition at Cannes in 2017) is about an absent husband and two people who are from different classes and also different ages... they are supportive of each other but in a very different way (from the relationship that Prabha and Anu, played by Divya Prabha, share in All We Imagine as Light). Over the years, we all perhaps have the same questions on our minds and one finds different ways to articulate them, film after film. My previous film, A Night of Knowing Nothing, was about an absent partner and also about friendship.

What was your relationship with Mumbai when you lived there and how has it changed after this film?

That is a very good question. I was born in Mumbai and I live there now, more than I live anywhere else. But my relationship with the city has always been that of an outsider. It is not like I had some para (locality) friends or something in Mumbai. I studied in Andhra Pradesh and I went to FTII in Pune, and so I don’t have that kind of a very local relationship with Mumbai, even though my family is from there. Which meant that when I came back to Mumbai after FTII, most of my friends were those who I met at FTII. So it was a new way to look at Mumbai, which was about struggling in the film industry, finding a roommate for your 11-month lease and things like that.... It was what everybody around me was talking about, though I was privileged enough to have a place to stay. Yet I understood their concerns. I think my relationship with Mumbai has changed now more and more because of my friends and how they see the city.

While making All We Imagine As Light, we did a lot of research regarding the history of the city. There is a very clear visual history of Mumbai. You see Lower Parel and then you see Dadar, which used to be the cotton mills when I was a kid but now has very swanky buildings. It is a totally different world. It is like a whole erasure of that past. Now it is happening more and more. I have always wondered what it means to the people who live there and what did it mean to the people who once lived there. I don’t have that much knowledge, but meeting different people, going to some meetings of people who used to live there and fought for the rights of their housing, taught me a lot about this history.

Is that why All We Imagine As Light shows the city through a lens that is free of stereotypes?

I was very sure that I wanted to show the train tracks... the going up and down on the Central Line and the Harbour Line... the two very internal train lines that are there in Mumbai. For me, having that in the film was the most iconic thing about Mumbai because that is what most people living in Mumbai see every day. You don’t always get a chance to go to the sea... that is a special thing.

Also, I wanted to show the skywalks. It is another thing which has become very common in Mumbai. Everybody has to climb that skywalk at some point or the other and it has become a place where you will also see people chilling. Some will be selling things on it. It has also become a place for couples, which is reflected in my film in Anu and her boyfriend’s (Shiaz, played by Hridu Haroon) need for privacy. I wanted to explore the concept of people finding solace in the city even in some not very nice-looking places.

That is why I wanted the love story between Prabha and Dr Manoj (Azees Nedumangad) to not be in a stereotypical place like a park. A park is pretty but how do you make a skywalk a memory of romance?

Also, I didn’t want to show the sea in Mumbai because I wanted that feeling of freedom and vastness of space to only come only in the second half when Prabha and Anu travel to Ratnagiri, which is a port town. We have that revealing shot of the sea where the camera pans to the sea and then to Prabhu and Anu’s expansive gaze as they stare at it. Their eyes have been waiting for it for so long.

Is there a little bit of you in all the three women in the film, including Chhaya Kadam’s spunky Parvaty?

I think only a woman can ask this question (smiles). It is true that there is a bit of me in all three characters. I desire to be more like Parvaty but I find myself oscillating between Prabha and Anu.

When I started writing the script, I was closer to Anu’s age. But it took me seven years to go from the first page to the final film and now, I am closer to Prabha’s age. So the way I look at my younger self or at the characters has changed.

Initially, I didn’t have so much empathy for Prabha’s character. Now I have much more. I feel that the film is a kind of self-reflexivity on how I feel I have behaved with people, especially women, and felt that maybe I had too much judgment then. I have tried to question myself a lot on that. That has kind of found its way into the film.

Dreams are a leitmotif in all your films. They are also often projected as reveries in your work. How do you explain this choice of narrative expression?

I think that dreams reveal something in the minds of the characters without spelling it out too clearly. You can create a visual ambiguity with a dream... whether it is an imagined visual or an actual visual from the film. That, for me, is very interesting. Dreams are an extra tool for a filmmaker, they present more possibilities to express the characters’ inner beings. That really excites me. Also, I am the daughter of a psychoanalyst. That has been very much a part of our lives and now makes its way to my films.

Your writing process in A Night of Knowing Nothing was largely organic. Was it also as non-premeditated in this film or did the presence of structured funding make you go in with more preparation and form?

It was much more structured, which was very new for me. I went in like a school student because they give you deadlines to follow. It is actually good because then no one will complain and say: ‘Oh I am not ready, my creative process is not there yet’.

Writing can be such a lonely thing... you could just go on and on. Having this kind of structure this time was really useful. But I also kept some of the quality of the first films’ writing in our process. Ranabir Das, who is the cinematographer on my films and who I work with very closely, and I would go out into the streets of Mumbai during the process of writing the scenes. He would shoot a lot of things — the rain, the way people are in the spaces of the city, the light which envelopes the city — and we would come back and rework the script with those new thoughts. So while scripting, it was kind of like a documentary. We also did a lot of interviews with strangers... like people we just met on the train. I operated from the point of curiosity of a documentary filmmaker.

That is also how the opening sequence of the film came about. We wanted to keep some of the stories we had found at that time in the film. That process is very nice because it allows the real world to come into your work.

Everyone is now looking at what Payal Kapadia will do next. Do all the firsts at Cannes — including winning the prestigious Grand Prix — put a wee bit of pressure on you?

Yes. I do feel a bit overwhelmed and nervous about how people in India will react to the film. When you make a film, you feel very fragile and vulnerable about it, no matter how many times it receives praise. The audiences are different everywhere. In India, it is different from one city to the next. I am nervous before every screening. I don’t think that ever goes away for any filmmaker....

You did get a taste of the Indian audience’s reception of the film when it showed at the MAMI film festival last month...

When you are showing a film at a festival, I feel that the audience is always very charged up. They are there to appreciate cinema, they are true lovers of cinema. The feel is very celebratory and everybody, at every film festival I go to, is in a very ‘cinephile mood’. That is an added advantage for any filmmaker, to be honest. A regular release in cinemas is different and also marks a first for me. I am definitely nervous.

Much has been said, written and debated about how All We Imagine As Light was short-changed and not picked to be sent as India’s entry to the Oscars. After the kind of journey that the film has had and will continue to have over the next year as it travels the world, do you think this whole focus on the Oscars is a little myopic?

Well, the Oscars are definitely up there. We all watch them, we root for the films and performances we like. It has a big role in the purpose of recognising and rewarding cinema. What I do feel is a bit pointless are the long debates about which film should have gone (as India’s pick) and which shouldn’t have gone. We don’t know on the basis of what these selections happen. I don’t think I have enough knowledge to speculate about a system that I am not very familiar with. Who really is, anyway?(Smiles) In India, we have so many films that never go to any festival but they are great films and they do very well with the Indian audience.

What are you working on next?

I am going to make another film in Mumbai, though I am very, very tempted to make a film in Calcutta. I have too many friends and family in Calcutta and I really love that city! Every time I am there, I feel that every little brick in that city is a story. But I think I will have to give Bombay one more chance and then hopefully I can make a film in Calcutta.

I am drawn to places where there is really good food and I think that is why I made a film in Malayalam! (Laughs) It gave me an excuse to go there all the time and eat lots of food and if I make a film in Bangla and it will be set in and shot in Calcutta, then it will give me another reason to eat! (Laughs)

What are your usual haunts in the city and which parts do you feel are very cinematic?

I roam around and go to Broadway (Hotel). I love that part (Ganesh Chandra Avenue) of the city so much. When my grandparents came to India from Pakistan during Partition, they settled in Calcutta. When I went back to Calcutta for the first time as an adult, I wanted to see where they lived. My grandmother has all these stories about going to Metro Cinema and Maidan. So I did an ode to my grandmother and visited a lot of these places from 1947 that are still around.

And then, as I said, there is the food. I love having the chimney soup at this restaurant run by a family. I cannot recall the name now. I really want to make a film in Calcutta because most people are cinephiles and I hope to get a big audience there for my films.