Jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, Netflix’s three-part documentary about the rise of Kanye West, does not dwell, or seek to correct the record, on the most well-known of the rapper’s celebrity blowups. George W. Bush, Taylor Swift, Donald Trump and Kim Kardashian hardly factor. There has never been a shortage of West analysing his own travails, after all.

Instead, relying on casual footage chronicling the lead-up to and immediate aftermath of West’s 2004 debut album, The College Dropout, the four-hour-plus film lingers on quieter, pre-fame moments: chats with his mother, Donda, about the difference between confidence and arrogance; the desperation of trying to play his demo CD for disinterested peers; a more respected artist being disgusted by West’s orthodontics retainer.

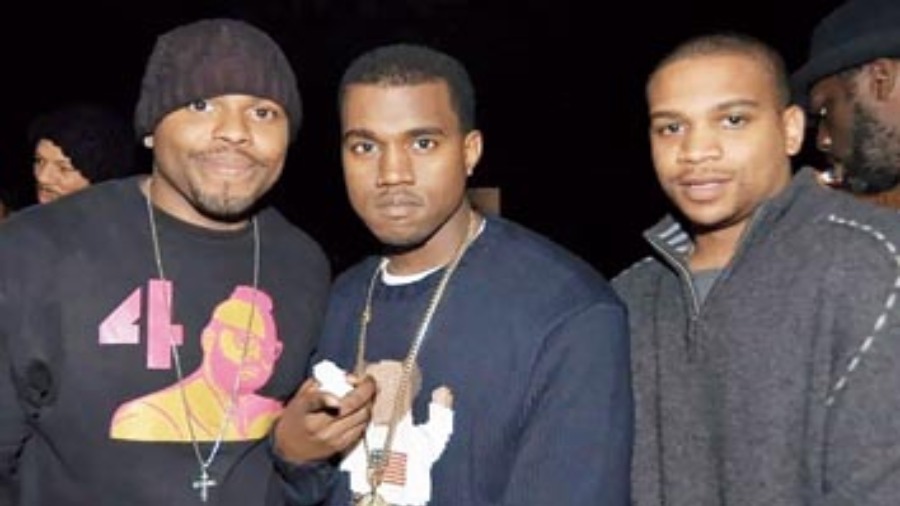

Behind the camera throughout was Clarence Simmons, a stand-up comedian-turned-director known as Coodie, who along with his creative partner, Chike Ozah, has been compiling video of West for more than 20 years. But that wasn’t always the plan.

Originally conceived as a Hoop Dreams-style feature, the documentary was supposed to end in the early 2000s, with West — who is now legally known by his old nickname, Ye — winning his first Grammy Award. But as West developed from a nerdy Chicago beatmaker for Jay-Z to a polarising, era-defining artist across music, fashion and more, he grew apart from Coodie, an old neighbourhood friend, and changed his mind about the project, leaving hundreds of hours of tape in limbo.

Following some false starts and brief reconciliations, the directing duo Coodie & Chike, as they are credited, finally found traction — and more time with West — in recent years, amid another uptick in controversy. West’s mental health struggles, disastrous 2020 presidential run and recent album named for his late mother all get some airtime in the third episode.

Yet the core of Jeen-Yuhs remains the verite depiction of West’s chrysalis years, with Coodie filling in the gaps in time by telling his own story of personal metamorphosis and creative ambition. “This is not the definitive story of Kanye West, this is the story told through the most unique perspective,” said Ian Orefice, the president of Time Studios, which co-produced the project.

Coodie and Chike discuss the long-gestating documentary, the ups and downs of living alongside mega-fame and West’s last-minute demands for final cut of the film. Excerpts.

Chike Ozah (right) and Clarence Simmons, known as Coodie, with Kanye West

The film begins with the premise that you always knew Kanye would make it big. What first convinced you that he was going to be a star?

COODIE: It started with his production. But then I would just keep running into Kanye, and I remember he was performing with his group, the Go Getters. He just commanded the stage. I was like, “This is the dude! The producer — he’s the one.” Then I saw how he loved the camera. He was loving the camera. He wanted to rap for anybody, and it was just like he was performing for a thousand people, but it’s just one person and he’s rapping to them.

What was Kanye’s original reason for not putting a film out back then? In the footage, he’s so excited to tell people you’re making a documentary

COODIE: He said: “Man, I don’t want nobody to see my real self.” He said, “I’m acting right now.” It was too intimate. But I feel like the reason why he was loving me filming him at the beginning was just because I was that dude, really. I was popular in Chicago — cool, funny.

CHIKE: You brought value to his brand in Chicago instantly, just by deciding to have him on Channel Zero [Coodie’s original hip-hop show on public access television].

COODIE: The greatest ambition was for him to win a Grammy, and I wanted to follow him to see it. But it’s definitely, definitely a blessing that it didn’t come out, because I didn’t know what I was doing at all.

What was it like to watch the rest of his rise from more of a distance?

COODIE: I was so proud ??to see him accomplishing all the things he was accomplishing. But then I felt left out, too. Like when he went to Oprah, I’m like, “I want to meet Oprah!”

CHIKE: It’s not all peachy and clean. I think that’s the case with anybody that’s on the rise to stardom like this. Coodie and I definitely felt what it’s like when outsiders come in and start jockeying for position. We had that Bryan Barber and Outkast vibe for a minute — like we’ll rise together and do all these music videos. But as he got bigger, more people started coming into the fold and you just get pushed out. Luckily, Coodie and I had a relationship and a bond together and we were able to find creativity elsewhere.

At that point, did you believe the project to be dead or did you always assume you would return to it eventually?

COODIE: I felt like we would come back to it someday. I used to look at all the mini-DVs, and the bigger he got, I knew how much more valuable my footage would be: One day in God’s time, this is going to happen.

He sat us at the table at Kris Jenner’s house, right before Pablo [the Life of Pablo album in 2016], he was like, “Man, you know, I get misunderstood a lot.” He asked us to be his voice. We thought it was time for the documentary to come out, for people to see the real Kanye. He was working with Scooter Braun at the time and we were at HBO with it. Then all of a sudden, they had other plans for Kanye. We were right there and it just went to nothing.

It felt, to me, that Kanye was crying out for help at that moment. Right after, he went on the Saint Pablo tour and that’s when he had the breakdown — he calls it the “breakthrough.” I was really, really worried. I thought we were supposed to help him and we weren’t able to because of the powers around him. Not only did I feel worried, I was extremely mad about it.

On a practical level, how did you keep all those tapes safe?

COODIE: I really didn’t even. You’d just see it in a duffle bag, shoe boxes.

CHIKE: But it’s like bricks of gold in there.

COODIE: It’s in storage now, though!

When did you know that you finally had his full buy-in?

COODIE: When I showed him the sizzle. He called me out of nowhere and said he was working on an album about his mom and he wanted to use some of my footage. He asked for my blessing and I said, “Oh, for sure, but I need your blessing for something. I’ll fly wherever you’re at.” His security called me like, “Can you come to D.R. tomorrow morning?” When I finally showed him the sizzle, he was like, “We’ve got to put this out tomorrow.”

Once the film was in motion, how involved did he want to be and how involved did you want him to be?

COODIE: He said: “Let’s me and you do it,” and I told him, “You have to trust me on this.” Meaning no creative control. I said, “It would not be authentic if you have it.” He got all of that. And that was it.

Do you have favorite stuff from the cutting room floor that you just couldn’t squeeze in there, no matter how much you wanted to?

CHIKE: There’s a scene when Kanye goes back to Chicago to perform at a tribute to people who were lost in the E2 tragedy [a stampede at a Chicago nightclub]. When he gets there, he ends up having to settle up a beef with another rapper. He almost gets a bottle cracked over his head — it gets real ugly. It could’ve gone somewhere worse. And Kanye’s not even that type of artist! But he still can’t escape the street mentality. And it deals with a beat that Jay-Z ended up with that helped propel Kanye’s career.

COODIE: It was Never Change on The Blueprint. He sold Jay-Z the track that he sold to [the Chicago rapper] Payroll as well. Payroll wrote the hook — “out hustling, same clothes for days.” Kanye let Payroll know he was about to sell it, but he also did Payroll’s hook. Kanye took care of Payroll after that, but Payroll was like, hold on … He said, “Kanye you’ve got to give me more.” I’m telling them like, nah! But for them to crush the beef was good, too.

Kanye is back in the tabloids these days because of his divorce. When you see this celebrity hurricane side of his life, do you worry for him?

COODIE: I used to worry, but I know that God has his back. He almost died in a car accident a couple of times — he had a car accident in Chicago even before he moved to New York, flipped his truck over. A couple other incidents that I’ve seen — God is really looking out for him, for whatever reason. When I see this now, I’m like, it’s going to pass like everything else did.

The New York Times News Service