Jean-Luc Godard, the daringly innovative director and provocateur whose unconventional camerawork, disjointed narrative style and penchant for radical politics changed the course of filmmaking in the 1960s, died by assisted suicide, having suffered from “multiple disabling pathologies.”

"He could not live like you and me, so he decided with great lucidity, as he had all his life, to say, ‘Now it’s enough,’” his longtime legal adviser, Patrick Jeanneret, said in a phone interview. Godard wanted to die with dignity, Jeanneret said, and “that was exactly what he did.”

A master of epigrams as well as of movies, Godard once observed, “A film consists of a beginning, a middle and an end, though not necessarily in that order.”

In practice, he seldom scrambled the timeline of his films, preferring instead to leap forward through his narratives by means like the elliptical “jump cut,” which he did much to make into a widely accepted tool. But he never tired of taking apart established forms and reassembling them in ways that were invariably fresh, frequently witty, sometimes abstruse but consistently stimulating.

As a young critic in the 1950s, Godard was one of several iconoclastic writers who helped turn a new publication called Cahiers du Cinéma into a critical force that swept away the old guard of the European art cinema and replaced it with new heroes largely drawn from the ranks of the American commercial cinema — directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks.

When his first feature-length film as a director, “Breathless” (“À Bout de Souffle”), was released in 1960, Godard joined several of his Cahiers colleagues in a movement that the French press soon labeled la nouvelle vague — the new wave.

For Godard as well as for new wave friends and associates like François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer, the “tradition of quality” represented by the established French cinema was an aesthetic dead end. To them, it was strangled by literary influences and empty displays of craftsmanship that had to be vanquished to make room for a new cinema, one that sprang from the personality and predilections of the director.

Although “Breathless” was not the first new wave film (both Chabrol’s 1958 “Beau Serge” and Truffaut’s 1959 “400 Blows” preceded it), it became representative of the movement. Godard unapologetically juxtaposed plot devices and characters inherited from genre films and emotional material dredged up, in almost diarylike form, from the filmmaker’s personal life.

The film tells the story of a small-time Parisian crook (Jean-Paul Belmondo) as he commits muggings to collect enough money to run off to Rome with an American student (Jean Seberg), who seems indifferent to his romancing despite being pregnant by him.

“Breathless” is an artistic hybrid that seemed to capture the discontinuities and conflicts of modern life, half in the artificial public world created by the media and half in the deepest recesses of consciousness. In Godard’s later, more radical phase, he came to suggest that there was no real distinction between the two realms.

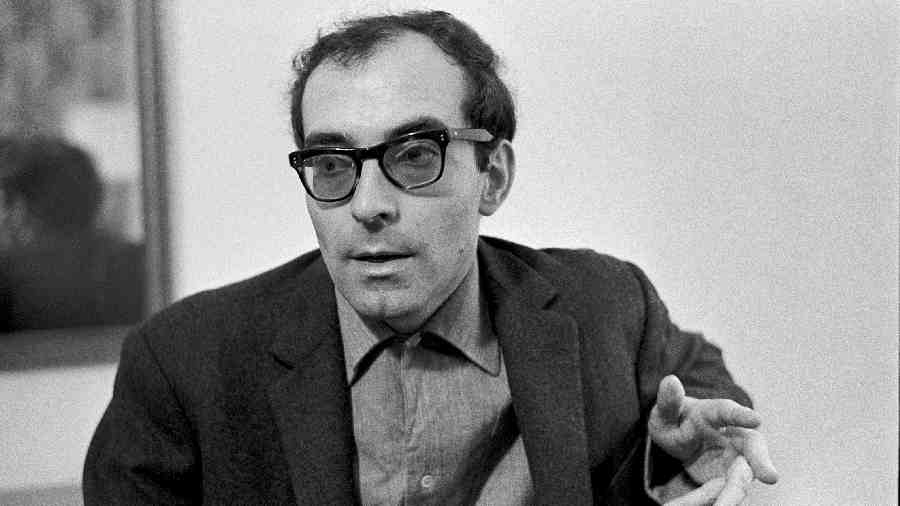

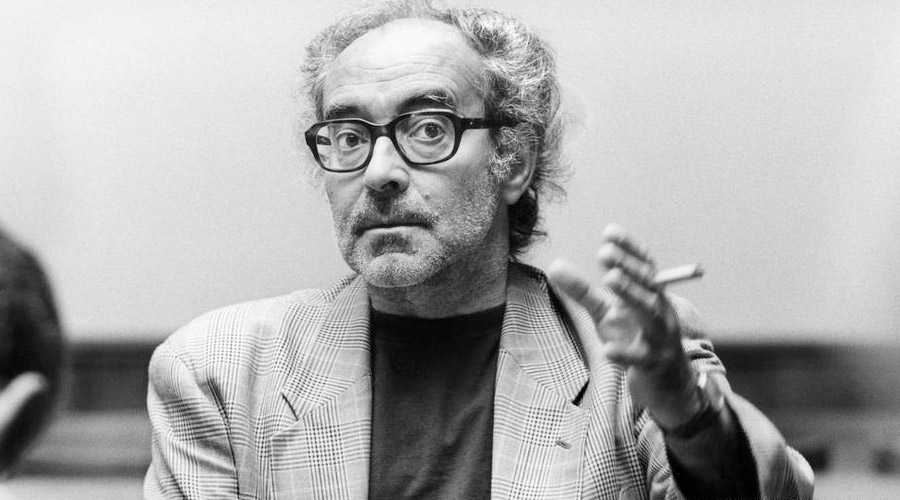

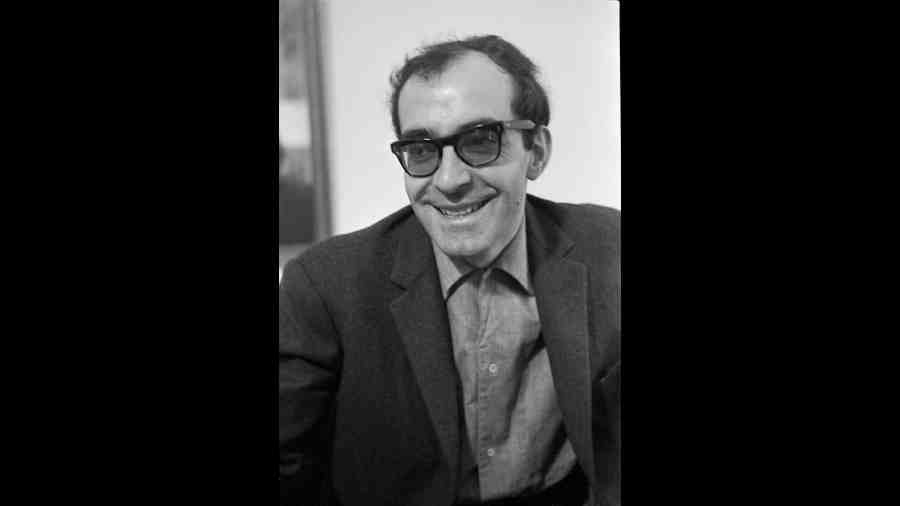

A short, slight, often scruffy man with heavy-rimmed black glasses and an ever-present cigarette or cigar, Godard rarely gave interviews. When he did, he typically deflected probing questions about his life and art.

A journalist’s query in 1980 about his decision to move out of Paris in 1974 to Grenoble, in the French Alps, and then to Switzerland, elicited several contradictory explanations — including an assertion by Godard that on a sudden whim one day, he had “just jumped into the car and took the highway.”

It was a description of a famous scene in “Breathless” in which Jean-Paul Belmondo impulsively steals an automobile in Marseille, France, and drives off into the countryside without a plan.

“The problem of talking to people is that I have always confused cinema with life,” Godard said in that interview. “To me life is just part of films.”

In 2010, Godard, long at odds with Hollywood, was awarded an honorary Oscar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for lifetime achievement, but not without controversy. The award revived long-simmering accusations that Godard held antisemitic views.

He did not attend the ceremony, and when an interviewer afterward asked him what the award meant to him, he was blunt.

“Nothing,” he said. “If the academy likes to do it, let them do it.”

Godard, the daringly innovative director and provocateur whose unconventional camera work, disjointed narrative style and penchant for radical politics changed the course of filmmaking in the 1960s, leaving a lasting influence on it, died on Tuesday, Sept. 13, 2022 Sam Falk/ The New York Times

Born into wealth

Jean-Luc Godard was born Dec. 3, 1930, in Paris, the second of four children in an extravagantly wealthy Protestant family. His French-born father, Paul-Jean Godard, was a prominent physician, and his mother, Odile Monod, was the daughter of a leading Swiss banker. Jean-Luc Godard credited his parents with instilling in him a love for literature, and he initially wanted to be a novelist.

Paul-Jean Godard, who became a Swiss citizen, opened a clinic in Nyon, Switzerland, and Jean-Luc Godard spent his early childhood there, visiting his family’s estates on both the French and Swiss sides of Lake Geneva and remaining there until the end of World War II.

After France was liberated, he returned to Paris as a teenager to attend secondary school, the Lycée Buffon, then enrolled at the Sorbonne in 1949, intending to study ethnology. Instead, he immersed himself in cinema, spending much of his time at the Cinémathèque Française, a nonprofit film archive and screening room, and in the film societies of the Latin Quarter.

It was at the Cinémathèque that he made the acquaintance of André Bazin, an influential film critic and theorist, and of the other young film enthusiasts in his circle, including Truffaut, Rohmer and Rivette. He began writing reviews for the magazine La Gazette du Cinéma in 1952 under the pseudonym Hans Lucas and later joined Truffaut, Rohmer and Rivette as a contributor to Cahiers du Cinema, which Bazin had founded.

When his parents refused to support him financially, hoping that he would take more responsibility for himself, Godard began stealing money — from his family members and their friends and even from the office of Cahiers du Cinema. This went on for five years.

He distributed some of the proceeds to fellow filmmakers, lending Rivette enough money to make his film debut with “Paris Belongs to Us.”

“I pinched money to be able to see films and to make films,” he told The Guardian in 2007.

After his mother secured a job for him with a Swiss television outfit, he stole from his employer and in 1952 landed in jail in Zurich. His father obtained his quick release, but only after Godard agreed to spend several months in a mental hospital.

He grew estranged from his parents, and when his mother died in a road accident in 1954, he did not attend the funeral.

A decade later, Godard paid homage of sorts to his mother in “Band of Outsiders,” a film about two thieves who romance a young woman living in a villa. The female lead, played by Anna Karina, a Danish model who was Godard’s wife (his first) at the time, is named, like his mother, Odile, and, like his mother, she detests movies.

Godard’s personal and professional lives intertwined throughout his career. His first marriage, in 1961, to Karina, ended in divorce in 1964. (She died in 2019.) In 1967, when he was 36, he married Anne Wiazemsky, an actress 16 years his junior who was starring in his film “La Chinoise.” Wiazemsky, who died in 2017, wrote two books about their marriage, which ended in 1979. Twelve years ago, he married Anne-Marie Miéville, who survives him.

Godard developed the outline of “Breathless” in 1959, inspired by a newspaper clipping given to him by Truffaut. For his stars, he chose Belmondo, the son of a well-known sculptor just at the beginning of his acting career, and Seberg, an American actress whom the Cahiers critics had admired for her performances in two Otto Preminger films, “Saint Joan” (1957) and “Bonjour Tristesse” (1958).

Godard remained best known for “Breathless” and about a dozen films he made in quick succession afterward, ending with “Weekend” in 1967. University audiences identified with the doomed romanticism of Belmondo’s central character in “Breathless,” a petty criminal who identified with the doomed romanticism of the characters played by Humphrey Bogart in the American films that Godard and his Cahiers colleagues admired.

On one level, “Breathless,” produced on a $70,000 budget, seemed to fulfill Godard’s famously dismissive dictum, “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun.” But the herky-jerky rhythm — with scenes sometimes out of sequence — fascinated and bewildered audiences.

Writing a few years after the film’s release, cultural critic Susan Sontag likened its impact on cinema to the effect the cubists had on traditional painting. And covering a 2000 revival screening of “Breathless,” essayist and novelist Philip Lopate said he felt as exhilarated by the film as when he first saw it 40 years before.

Other great avant-garde films were released about the same time: Michelangelo Antonioni’s “L’Avventura” (1960), Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” (1959) and Ingmar Bergman’s “The Virgin Spring” (1960). “Yet only ‘Breathless’ seemed a revolutionary break with the cinema that had gone before,” Lopate wrote in The New York Times. “It seemed a new kind of storytelling, with its saucy jump cuts, digressions, quotes, in jokes and addresses to the viewer.”

The film became an international success, one of the bigger commercial hits of Godard’s career. There would even be an American remake in 1983 starring Richard Gere.

Jean-Luc Godard was born Dec. 3, 1930, in Paris, the second of four children in an extravagantly wealthy Protestant family Sam Falk/ The New York Times

Enter politics

But rather than repeat the winning formula of “Breathless,” Godard introduced an element of radical politics into his next film: the gray, somber “Le Petit Soldat,” which criticized French conduct in the Algerian war for independence. The film was banned from French theaters for three years, during which time Godard directed a candy-colored, widescreen homage to the Hollywood musical “A Woman Is a Woman” (1961), starring Karina, and the stark, Scandinavian-influenced “My Life to Live” (1962), which cast her as a Paris housewife who drifts into a life of prostitution.

In 1963, Italian producer Carlo Ponti offered Godard a hefty budget and the services of Brigitte Bardot, then at the height of her international popularity, to create a film version of the Alberto Moravia novel “Il Disprezzo.” The resulting film was “Contempt,” the story of a screenwriter (played by Michel Piccoli) who is hired by a venal American producer (Jack Palance) to punch up the script of an “Odyssey” being filmed in Rome by a veteran Hollywood director (Fritz Lang, playing himself).

The screenwriter struggles to maintain his integrity in regard to both his work and his wife (the producer appears to have designs on both) but finds his self-respect slipping away. Amid the usual Godardian fireworks — which include shots of Bardot’s nude backside, inserted to satisfy Ponti’s contractual demands — “Contempt” retains a quiet sense of human tragedy that for many critics makes it the masterpiece of Godard’s first period.

As the 1960s unfolded, Godard continued to work at a breakneck pace, turning out sketches for compilation films — including “RoGoPaG” (1963) and “Paris vu Par ” (1965) — alongside features like “Band of Outsiders” (1964), “Une Femme Mariée” (1964), “Pierrot le Fou” (1965) and “Masculin Féminin” (1966).

In “Alphaville” (1965), Godard plucked a character from the French popular cinema, private detective and secret agent Lemmy Caution, along with expatriate American actor Eddie Constantine, who had played Caution (or variations on the character) in many films, and dropped him into a dystopian future ruled by a giant computer.

Despite his stylistic innovations, at this point Godard saw the world in traditional Romantic terms: as a struggle of a heroic individual against the forces of conformity and oppression.

That changed in February 1968 when Godard, along with several new wave colleagues, stepped forward to protest the decision by the French minister of culture, André Malraux, to force Henri Langlois to resign as chief of the Cinémathèque Française, the film archive that Langlois had helped found in 1936.

Demonstrations filled the streets and quickly grew to embrace impatient demands for a general restructuring of French society.

By the end of April, the demonstrations had grown violent. Two weeks later, Godard joined with Truffaut, Alain Resnais, Claude Lelouch, Louis Malle and other film figures to close down the Cannes Film Festival. The protests of May 1968 were in full swing, and Godard was swinging with them, lashing out at his fellow filmmakers for failing to demonstrate sufficient solidarity with France’s striking students and workers.

For his part, Godard abandoned commercial cinema and plunged into radical politics, embarking on a series of films, financed on the fly and shot in economical 16-millimeter, that tried to leave fiction behind. After a pair of aggressively didactic films, “Un Film Comme les Autres” (1968) and “Le Gai Savoir” (1969), and an abortive project with the Rolling Stones, released against Godard’s wishes as “Sympathy for the Devil” (1968), Godard joined with filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin to create a collective they named the Dziga Vertov Group, after the Soviet filmmaker whose efforts to create a new form of political documentary they much admired.

The films of this period, which include “The Wind From the East” (1970), “Struggle in Italy” (1971) and “Vladimir and Rosa” (1970), did not find wide distribution or wide acceptance, although they remain valuable artifacts from a tumultuous time and helped open the way to the equally provocative but less ideologically confined films that followed.

A 1972 attempt to move the ethos of the Vertov Group into the mainstream with the 35-millimeter feature “Tout Va Bien,” starring Jane Fonda and Yves Montand, was not a commercial success, though it did yield a short film, “Letter to Jane,” which pointed the way toward the last third of Godard’s career.

As the camera scrutinizes a still photograph of Fonda taken in Hanoi, Vietnam, Godard, in voice-over, analyzes her expression and tries to situate the news photo within the context of publicity stills taken for Hollywood films, including a shot of her father, Henry Fonda, as Tom Joad, the hero of “The Grapes of Wrath.”

Jean-Luc Godard shaped the French New Wave Sam Falk/ The New York Times

‘Becoming an Adult’

Godard would carry this minimalist approach and essayistic structure into the emerging realm of video art, with works like “Numéro Deux” (written with Miéville) and the six-part television series “Six Fois Deux/Sur et Sous la Communication.”

These radically discontinuous works use rapid dissolves and densely layered soundtracks to escape linear narratives and ordered, rational arguments, plunging the viewer instead into a barrage of conflicting impressions, wildly assorted quotations, elaborate puns and paradoxical observations.

Godard said of the series, which attracted a lot of publicity but few viewers, “It isn’t even a sketch. It’s the eraser, the paper to make the sketch.”

In 1979, Godard moved again, this time to Rolle, Switzerland, where he kept a home and production office — along with another on the outskirts of Paris — for the remainder of his career.

Beginning with his gingerly return to mainstream filmmaking in 1980, with “Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie)” (released in English as “Every Man for Himself”), Godard would move back-and-forth between feature-length theatrical films, often with major stars (“Détective” with Johnny Hallyday, “Nouvelle Vague” with Alain Delon, “Hélas Pour Moi” with Gérard Depardieu) and shorter, more casual film and video pieces intended for television and festival viewing.

Those works often featured Godard as himself, commenting on just-completed films (“Scénario du Film ‘Passion,’” 1982), rattling around his home in Switzerland with Miéville (“Soft and Hard,” 1986), interviewing celebrities (“Meetin’ WA,” 1986, with Woody Allen) or contemplating his own mortality (“JLG/JLG — Autoportrait de Décembre,” 1995).

In 1988, he began one of his most ambitious projects, a seven-part series on the history of film, “Histoire(s) du Cinéma,” which he completed in 1998. This maddeningly dense, allusive work is composed of film clips — everything from Hollywood classics to hardcore pornography and concentration camp footage — accompanied by snatches of classical music and Godard’s off-screen ruminations on the morality of image-making and the role of film in the 20th century.

“When I made ‘Breathless,’ I was a child in movies,” Godard said in a 1992 interview with the Times. “Now I am becoming an adult. I feel I can be better. I think that artists, as they grow older, discover what they can do.”

As he grew older, Godard seemed more intolerant of other film directors. He quarreled bitterly with Truffaut, once his closest friends among the new wave directors.

He was especially scathing toward Steven Spielberg. In the 2001 film “In Praise of Love,” he portrays Spielberg representatives trying to buy the film rights to the memories of a Jewish couple who fought in the French Resistance. Commenting on the film’s sourness, Times critic A.O. Scott wrote in 2002 that it “completes Mr. Godard’s journey from one of the cinema’s great radicals to one of its crankiest reactionaries.”

Godard’s personality was as difficult to warm to as many of his films were. Biographers filled page after page with details of his feuds and schisms. He and Truffaut got into a spat after the release of Truffaut’s “Day for Night” in 1973 and never reconciled before Truffaut died of a brain tumor in 1984. When a talk show interviewer reunited Godard and Karina in 1987, Godard’s indifferent response to a question about their romance caused Karina to leave the set.

As for the accusations of antisemitism, which surfaced at various times over his career, fueled both by his remarks and by some of his films, Godard gave a typically elusive response to an interviewer in 2010.

“All peoples of the Mediterranean were Semites,” he said. “So antisemite means anti-Mediterranean. The expression was only applied to Jews after the Holocaust and World War II. It is inexact and means nothing.”

Yet regardless of his personal flaws and the fact that few of his movies found a mainstream audience, Godard was and still is an important influence on aspiring filmmakers. Quentin Tarantino, for instance, named a production company that he formed in 1991 A Band Apart, after Godard’s film “Band of Outsiders.” (“Bande à Part” was the French title.)

“To me, Godard did to movies what Bob Dylan did to music,” Tarantino once said. “They both revolutionized their forms.”

Godard insisted that despite his disappointment with contemporary Hollywood, he remained enamored of the great American directors of the past.

“We thought we could do better than the bad films, but not better than the good,” he said in a 1989 Times interview. “Myself, I never thought I would do better than John Ford or Orson Welles, but I thought I could perhaps do what Godard was meant to do.”

The New York Times News Service