Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse contains a vital element that has been missing from too many recent superhero movies: fun. Most of the better specimens of the genre, as well as the worst, assume a heavy burden of self-importance: the future of the planet, the cosmic balance of good and evil, the profit margins of multinational corporations and the good will of moody fans all depend on the actions of a gloomy character in a costume. Or a bunch of them. The alternative is an abrasive self-consciousness that pretends to be subversive but quickly turns sour and cynical. Either way, these movies can feel like a lot of work.

We can argue about that some other time. My point here is that this animated reworking of the Spidey mythos is fresh and exhilarating in a way that very few of its live-action counterparts — including the last couple of Spider-Man chapters — have been. Its jaunty, brightly colored inventiveness and its kid-in-the-candy-store appetite for pop culture ephemera give Into the Spider-Verse some of the kick of the first Lego Movie. The responsible parties (Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey and Rodney Rothman directed a screenplay by Rothman and Phil Lord) also hold onto the traits that have defined Spidey for more than 50 years. He is still a cerebral, introspective teenager from outer-borough New York, contending with existential confusions and merciless supervillains.

He isn’t Peter Parker, though. Well, he is and he isn’t. Playing with a conceit borrowed from theoretical physics — the hotly contested “multiverse” hypothesis — Spider-Verse proposes a multiplicity of web-slingers from different dimensions, all of whom converge thanks to disruption in the space-time continuum. There are a couple of Peter Parkers (voiced by Chris Pine and Jake Johnson). Also a futuristic anime heroine (Kimiko Glenn) with a robot spider, a cartoon pig (John Mulaney), a black-and-white film noir avatar (Nicolas Cage) and a canonical Spider-Woman, aka Gwen Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld).

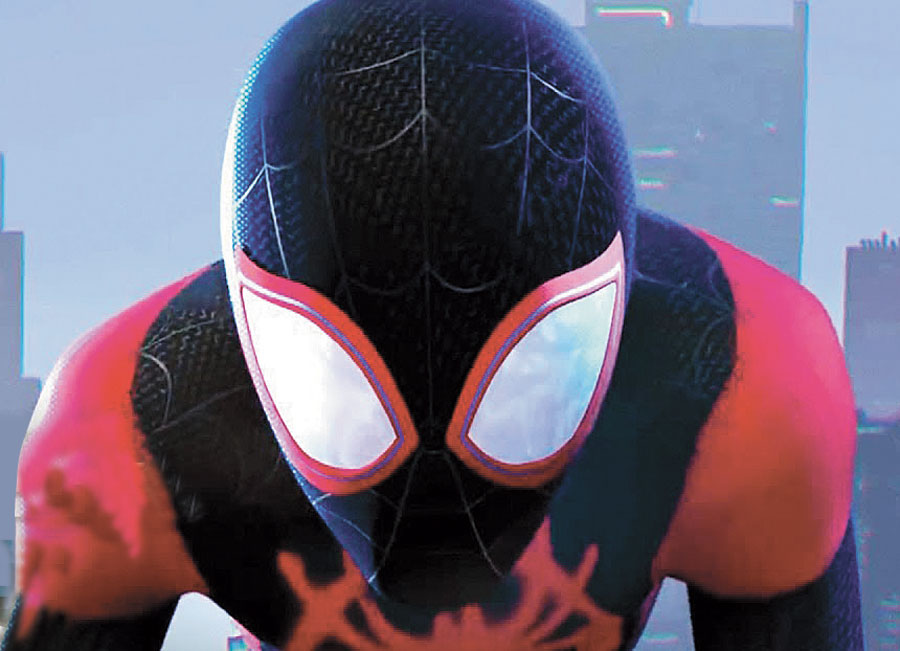

The main Spider-Man, in whose universe a variation on the familiar origin story unfolds, is a Brooklyn middle schooler named Miles Morales (Shameik Moore). The son of a hospital worker (Luna Lauren Velez) and a police officer (Brian Tyree Henry), Miles is a new transfer to an elite boarding school, where the side effects of the radioactive spider bite compound the usual humiliations and anxieties of adolescence.

We’ve heard that before, and also encountered most of the baddies who oppose that power. Doc Ock, Kingpin, Scorpion, Green Goblin. But we haven’t seen a Spider-Man like Miles onscreen, which is to say a Spider-Man who isn’t white. Part of the beauty of Spider-Verse is that Mile’s identity is both a very big deal and no big deal at all, at once a breakthrough and an affirmation of the ethos that has defined the character from the beginning.

The original Spider-Man, an upwardly striving, working-class New York kid, was also a child of the ’60s, a beacon to outsiders and rebels of every color and background, an instinctive democrat and a natural pluralist. More recently, Marvel, in print, movies and television adaptations, has tried to make inclusiveness a central aspect of fan culture and corporate practice. Spider-Verse accomplishes this without awkwardness, preening or preaching. It’s a movie for everyone.

And, as I was saying, a lot of fun. The story is clever and just complicated enough, moving quickly through silly bits, pausing for moments of heart-tugging sentiment, and losing itself in wild creative mischief. It is referential (and reverential) enough to Marvel traditions to please the geek armies, and perfectly accessible to new recruits or part-time warriors.

The characters feel liberated by animation, and the audience will, too. Old-style graphic techniques commingle with digital wizardry. Wiggly lines indicate the tingling of spider senses, while electronic bursts signal the presence of interdimensional static. The rules of visual coherence are tested and ultimately upheld, while the laws of physics are flouted with sublime bravado.

Even the climactic showdown — lately the dullest, noisiest, least imaginative part of any superhero movie — has a crazy, psychedelic intensity. In large-scale live-action filmmaking, digital effects have lost much of their luster, serving less as tools for innovation than as shortcuts to bombast. Spider-Verse, analog in sensibility if not in technique, finds greater imaginative freedom in venerable comic book traditions.

It finds realism, too. This may be the first Spider-Man feature to qualify as a great New York movie, drawn from the life of the city rather than outdated stereotypes. Streets and subways, apartments and schoolyards are beautifully and faithfully drawn, as are humans of all ages, shapes and hues. The people talk fast, the music is loud and sometimes hectic, and everyone is in motion all the time. Even the tourists from other universes are sorry to leave.