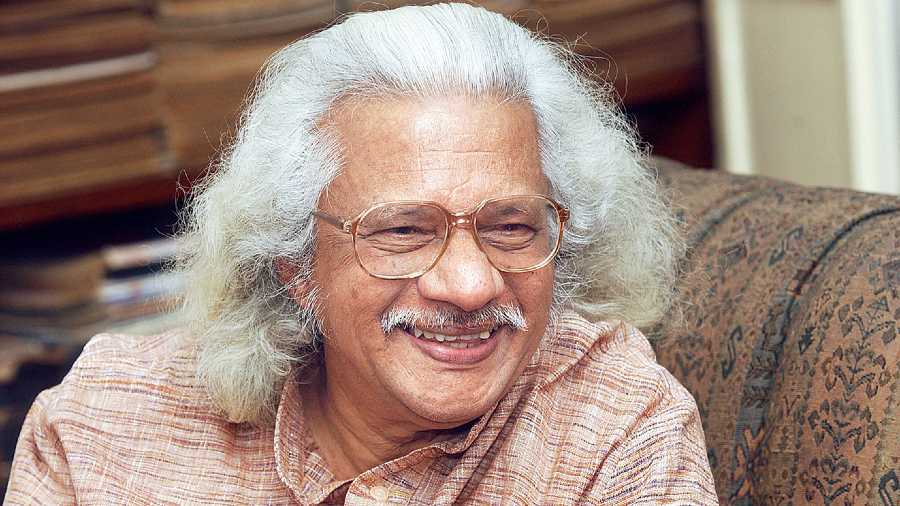

Adoor Gopalakrishnan needs no introduction. One of the leading lights of Indian cinema, a man who has taken our films to the biggest platforms globally, the film-maker ushered in the new wave of Malayalam cinema in the 1970s, but in a career spanning five decades, has only made about a dozen feature films. But each film — from the almost one-man Mammooty show in Mathilukal to Kathapurushan, which traces a metaphorical journey of 45 years, from Nizhalkuthu, that explores the recesses of the human consciousness to the striking monologue-film Anantaram — has been discussed, debated, lauded and feted across the world. Nearly all of his films have premiered at Venice, Cannes and the Toronto International Film Festival, with the film-maker having won the National Award 16 times, and the Kerala State Film Awards 17 times.

Honoured with the Padma Shri and the Padma Vibhushan, Gopalakrishnan received the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 2004. Besides being on the jury of many an international film festival and winning laurels worldwide, the film-maker has held many important posts, such as heading the National Film Development Corporation of India and the Pune Film and Television Institute of India. The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee has established an archive and research centre named the Adoor Gopalakrishnan Film Archive and Research Center where research students have access to 35mm prints of the feature films and documentaries made by Gopalakrishnan.

Gopalakrishnan, who last made a film in 2016, turned 80 yesterday. But the man has lost none of his sense of humour or the spark that makes him one of the greatest film-makers alive today, as we discovered during this freewheeling chat, peppered with laughs and truths.

Let’s first talk about Calcutta. You have always been vocal about your fondness for Calcutta. You have, of course, always had a firm friendship with film-makers Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen. For you, does the city mean them?

In the early years, whenever I would visit Calcutta, I would make it a point to go and visit Ray. He was my main connection to your city. I would spend a lot of time with him. When I had a film, I would invite him to the screening. After the screening, he would invite me to his residence the next day to talk about the film. That was our regular thing.

Once Ray was gone, then it was Mrinal Sen... Mrinalda... I had the same kind of relationship with Mrinalda as I had with Ray. It was, in fact, for a longer period because Mrinalda lived much longer, though he and Ray were almost of the same age. Just a few months before he died, I was in Calcutta. There was a retrospective of my films being held, and I went to see him. Now that he’s also gone, there is very little attraction for me in Calcutta.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan with Mrinal Sen in Calcutta

Calcutta has been a very important city for me. I feel at home in Calcutta. It’s not like Bombay or Delhi... it’s not like any other place in the country. It’s very Indian and rooted. I still have a few friends in the city.... It’s been a very important city in my life as a film-maker. It’s a city of great film lovers, it’s a place which has nurtured all these great film-makers. Calcutta featured so prominently in their films. Both Ray and Sen made many films on the city. But they had completely different approaches. Even when they spoke about the common man, their approach was very different. Reality was shown in the same way, but the approach was personal and subjective. That is what makes cinema the art form that it is.

I was brought up on great literature written in Bengali and translated into Malayalam. I read Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Durgeshnandini in translation during my schooldays. Sunil Gangopadhyay’s works have been a big favourite. I knew him, of course.

How much did the cinema from Bengal influence and shape you as a film-maker?

In my younger days, the most important film-makers from Bengal were Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, and Mrinalda came into prominence later. Ray had instant recognition everywhere, right from Pather Panchali. Once Mrinalda made Bhuvan Shome, he shot into the limelight. Mrinalda was a rebel in the real sense, and he didn’t fear experimentation. Often, it was at the cost of his popularity. I admired his integrity, in his character and his work.

He would lecture at the Film and Television Institute of India long after I had finished studying there. He would tell the students there that to become a good film-maker, one had to dream cinema, one had to live cinema.... It’s very true.

Cinema can’t be a casual affair, it’s not something that you do along with various other things. It has to be a single-minded passion. Cinema used to be, but not today, the most complex form of art. That’s because it’s a very strange mix of art and technology. So you had to master the technology to express your art. If your knowledge of technology is poor, then your art won’t come across.

Ray, Ghatak and Sen were the troika of our cinema... the great masters. Today, it’s become all digital. But we are yet to find our digital masters.

Which is what my next question is. Your 2016 film Pinneyum was your first digital film. Was it a difficult transition?

Not at all. What I feel bad is that many technicians lost their jobs because they couldn’t cope up with the technology. In my case, since I studied cinema in a formatted and academic way, adapting to a new technology was not that difficult. In fact, technology has become so accessible to the common people, that everyone is a film-maker now (laughs). Literacy has become widespread, but does that mean that everyone who writes is a writer? (Laughs) It depends on what you are doing with the knowledge that you have. Film-making, at least in the past, required a whole lot of preparation. Today, it’s on your mobile phone. Everything is made-to-order. You just have to press the button and it is there. Technology is now available at a click. That has also given people the impression that it’s very easy to make films.

In the older system, one had to give serious thought to the subject one chose, then how to develop it into different stages — one had a theme, synopsis, treatment, script, breakdown.... The preparation went on for months, sometimes even for years. And even when one shot a film, so much planning was required. And in those days, when we shot a film, we couldn’t see it until the film was processed and a negative was made. From the negative, we had to print the rushes or the positive print. That took a long time. And then after that, we had to sit down very patiently and start editing it.

All that has been made easy now. Now you can immediately see what you have shot. You can do a hundred takes if you aren’t happy. Technology has made film-making look easy, which I think is very misleading. At the end of the day, technology or not, you need to make a good film and be assured of a good audience. Technology doesn’t get you that... a good story does. That’s the real test. You have to communicate to at least some people who think like you do. Even in the past, there used to be the Super 8 technology but that disappeared.

Your style of film-making has always been about never revealing your script in entirety to your cast and crew. How has that served you as a film-maker?

I tell them about their roles very briefly, but not before. Only when they come on set, I tell them the basics of their roles. I tell them, ‘This is your character and this is what you will do now in the scene that is being shot’. But I don’t tell them anything more than that. It doesn’t help...

In an age where actors insist on bound scripts and extensive preparation, is that still possible?

As a director, one has to have a total vision of what you want your film to be and everything has to then submit to that vision. Everyone should single-mindedly work towards realising that vision. That’s why I don’t want my actors to independently interpret the film in their own way. That can be a disaster! (Laughs) Also, most actors, when they are not specifically told what to do, they have only one way of doing it. That’s what they are used to. As a director, one has to mould them into what you want them to do.

I do take several rehearsals, it’s not that I don’t. Even established actors turn to me and ask me, ‘Sir, I am not able to do this. Can you please show me?’ So I have to show him. Also, I tell them that I am not trying to tell them that they are useless actors (laughs), but the thing is that I want to get the best out of them. That may be one reason why six of my actors have won National Awards. So, as you can see, my method works!

Was there an epiphanic moment when you decided to dedicate your life to films and film-making?

For a long time, I wasn’t really aware of cinema and its possibilities. I was purely a theatre person, I was writing plays and also acting in those plays. Even after joining the institute (FTII), I produced a play... Waiting for Godot, I translated it into Malayalam. Even after joining the institute, I was still reading about and was engrossed in theatre production.

In my second year at the institute, I slowly turned towards films. That’s because I started watching a lot of films and then I was gradually drawn towards cinema.

And then I decided that I wouldn’t do anything else. Even when I don’t make films, I don’t do anything else. I have long intervals between my films, but that doesn’t mean I am doing anything else (laughs). I enjoy reading, living as a regular citizen....

I like my stories to come from the life I lead between my films. I take so much time between films because it allows me to get out of my previous film. I don’t want to make a film before the previous one is out of my system. I love this whole gestation process. I have to really feel compelled to make a film... then only I start my next one. People keep asking me, ‘What’s your next film about?’ I tell them, ‘I don’t know yet!’ I get very surprised when other

film-makers say , ‘I have two-three ideas in my head to make a film’. I tell myself, ‘I don’t even have one idea!’ (Laughs)

A young Adoor (centre) with Satyajit Ray (left) and Girish Karnad

But the world should have got many more films from you...

Ray asked me once, ‘Now that you have the recognition, why don’t you make at least one film a year?’ I told Manikda (Ray) that I wished to do so, but somehow it has never worked for me. In the beginning, it was very difficult to get funding to make my films. And then it became a habit for me to take my own time. I don’t like to hurry through anything. The result is that I don’t have any excuse to make for any film that I have made. I am happy with all of them. I tell myself at that time of my life I couldn’t have made a better film.

So you don’t revisit your films?

No. I don’t want to redo any of my films. Nor do I want to make a sequel to any of them. I don’t believe in sequels.

You don’t watch them at all?

Sometimes I am forced to! When there are retrospectives in other countries, and the venue of the screening is far from my hotel and I have a Q&A after the screening, then I have to stay back and suffer my own films! (Laughs) And by doing that, I have learnt something. That each film evokes a different response in different audiences. Some of my films did exceedingly well in France, while some did well in Germany but not in France. But I don’t get misguided by these responses. Because I make what I like... not what others would like.

Do you watch the films of today?

I try and see the meaningful ones... I don’t have patience for bad films, absolutely not! I respect film-makers who don’t compromise... they may not make great films, but they don’t compromise in what they believe... and that, in itself, is a value. I am sometimes called for previews and screenings and I go for some. But after the screening, I would be asked, ‘So how do you like the film?’ So I generally run away before the film ends, giving the excuse of some last-minute work! Once I ran away and the maker of the film ran after me! (Laughs)

There are some films in recent years that I have liked, though. It’s surprising how young film-makers are making such good films. In Malayalam, I like the work of Sanal Sasidharan. Then another director I like is Vipin Vijay.

I generally don’t watch Hindi films. But I do watch regional films. I really liked Court (by Chaitanya Tamhane). The Marathi industry is making some good films. In Hindi, many years ago, I liked Udaan (by Vikramaditya Motwane).

So what do you do when you aren’t making films?

I read a lot. I should have something to read all the time. I subscribe to a lot of newspapers, around five.

Do you watch anything on streaming platforms?

I don’t. In fact, I even removed my television set. I sold it for Rs 1,000!

We pick our favourite Adoor Gopalakrishnan films

Elippathayam (1981)

Elippathayam was Gopalakrishnan’s first film to be shot in colour. In this film, he conjures an episodic chain of events within a patriarchal household of Kerala in the 1940s. Mapping the last remains of feudalism through intricately drawn visual metaphors and recurring motifs, Elippathayam revolves around Unni (Karamana Janardanan Nair) and his three sisters, within their ancestral household. Captive to his unviable feudal outlook, Unni’s slow yet unavoidable disintegration forms the narrative crux that equates him to a rat in a trap. Enigmatic, lyrical and distinctly original, Elippathayam is Gopalakrishnan’s masterpiece that is as relevant now as it was then, in its intersection between distinct generational values.

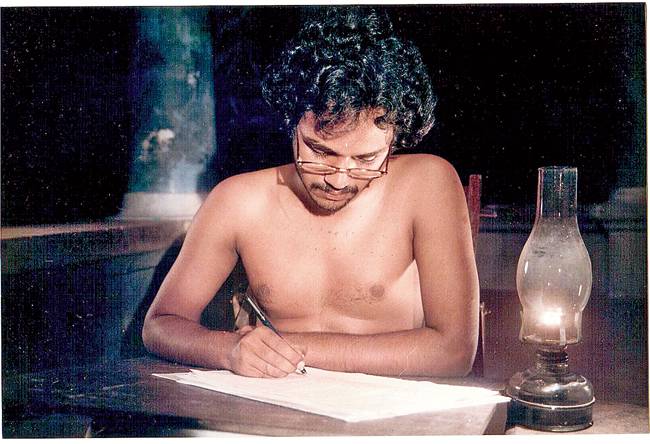

Mathilukal (1989)

In what is widely regarded as Mammootty’s finest screen performance, the actor starred as the celebrated writer Vaikom Muhammed Basheer in Mathilukhal, imprisoned in Trivandrum Central Jail for defying the salt laws. Gopalakrishnan details the daily routine of Basheer with tenderness and care, and accelerates the action only in the last quarter of the narrative when Basheer falls in love with a female inmate (K.P. A.C. Lalitha), communicating within the walls of the cell. We never meet her. They never meet each other too. Love blossoms beyond these borders. Compelling from the very first frame, Mathilukal is pure Gopalakrishnan magic, and feels unmistakably urgent in a generation where voices of dissent find themselves invariably behind bars.

Kathapurushan (1995

Fiercely autobiographical, Gopalakrishnan based Kathapurushan on his own experiences through the character of Kunjunni (Vishwanathan), as he stands witness to landmark events of India’s sociopolitical history, including the Independence, communist rule in Kerala, and Gandhi’s assassination. Kunjunni’s journey from Marxist philosophy to Naxalism, and then his subsequent imprisonment, spans decades, and Gopalakrishnan follows this journey with ruthless clarity of subsequence. Hauntingly beautiful and emblematic in its attention to detail, Kathapurushan is a definitive work in Indian cinema.

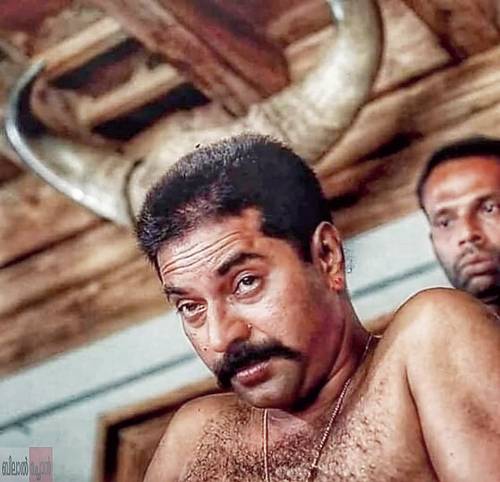

Vidheyan (1994)

Starring Mammootty and M.R. Gopakumar, this adaptation of the Paul Zacharia novella Bhaskara Pattelarum Ente Jeevithavum, builds up mostly through close-ups, setting the master-slave dynamic through static camera angles and visual metaphors. A meditation on the dichotomy between power and powerlessness, Vidheyan’s protagonist Patelar (Mammootty) revels in terrorising and oppressing the entire village, especially the meek migrant labourer (M.R. Gopakumar). Unlike his earlier films, Vidheyan is direct in the depiction of how power operates through terror and violence, without giving any space for understated elegance. Stark in its abject realism, Vidheyan is an unsparing film that holds a mirror to the current forces of religious fundamentalism and communal violence.

Mukhamukham (1984)

Seen as a pro-communist movie at the time of its release in 1984, Mukhamukham takes his viewer right into the minds of a revolutionary hero. Set against the backdrop of the rise and fall of Marxism in Kerala within the span of 25 years, Mukhamukham plays with fact and fiction, real and imaginary to present the left political discourse and its resultant collapse through the figure of Sreedharan (P. Gangadharan Nair). Gopalakrishnan’s critique remains sharp yet elusive, using cinema as a powerful medium of bringing the realities of a political ideology to life. No other Indian film has dared to walk the road that Mukhamukham did, in chronicling the chequered history of political activism.

Anantaram (1987)

A landmark film in terms of narrative experimentation, Anantaram is Gopalakrishnan at his enigmatic best, seamlessly weaving two stories through a single protagonist, merging character and setting. At the centre is Ajayan (Ashokan) who tells two personal stories in first person, becoming an unreliable thread to the chain of events that follow, and the audience is left to assimilate them into order. But Gopalakrishnan asks, is there any order in the state of experience?

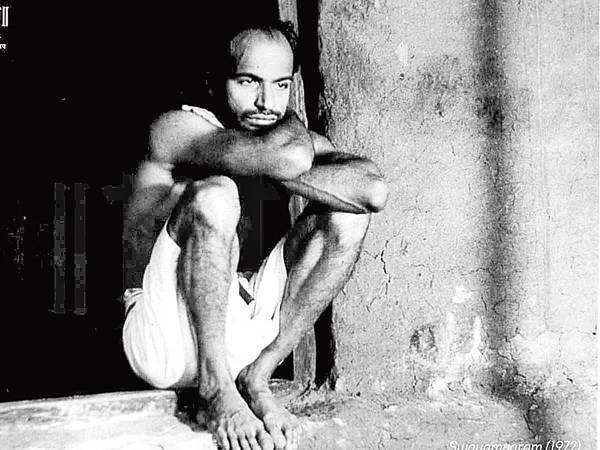

Swayamvaram (1972)

Gopalakrishnan won the National Award for Best Director for his remarkable feature film debut Swayamvaram, chronicling the marriage of two individuals, played to perfection by Sharada and Madhu. A pioneer in terms of introducing the new wave cinema movement in Malayalam cinema, Swayamvaram is also the first Indian film that uses sound as a leitmotif. Uncompromising in its neo-realistic approach and unforgettable for that haunting open-ended finale, Swayamvaram is an urgent film, palpable in its urge to preserve individuality in the modern age.

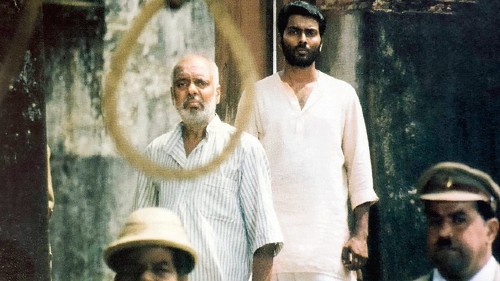

Nizhalkuthu (2002)

Set in the early 1940s, Nizhalkuthu tells the story of an executioner, Kaliayappan (Oduvil Unnikrishnan) who finds himself following the orders of the state. He questions his existence behind the performance, his guilt behind the deed, within a state that absolves itself of it. Graced with Gopalakrishnan’s trademark lyricism suffused with hard-hitting realism, Nizhalkuthu is an uncompromising piece of work, signalling the ways in which the individual finds himself chained to the regimes of the state machinery at work.

Naalu Pennungal (2007)

Divided into a series of four stories revolving around four women without any direct connecting thread, Naalu Pennungal is adapted from Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s short stories. Organically linked in its depiction of the conditions of women in a bygone era that have not changed for the better in the present, Gopalakrishnan creates an omnipresent cultural framework through the stories of the prostitute, the virgin, the homemaker and the spinster. Naalu Pennungal is an unusual, exciting film from a director who is constantly subverting the ways in which a subject is placed within the objective reality of a civilisation.

Kodiyettam (1978)

Gopalakrishnan’s character study of an irresponsible, careless man who transforms himself to be a sensible individual is particularly unforgettable for Bharath Gopi’s brilliant performance as Shankarankutty, for which he won the National Award for Best Actor. Sharp in its perception of a society that accepts individuals based on their merit, Gopalakrishnan hints indirectly at his audience to accept Shankarankutty based on his position or his morals.

Compiled by: Santanu Das (t2 intern)