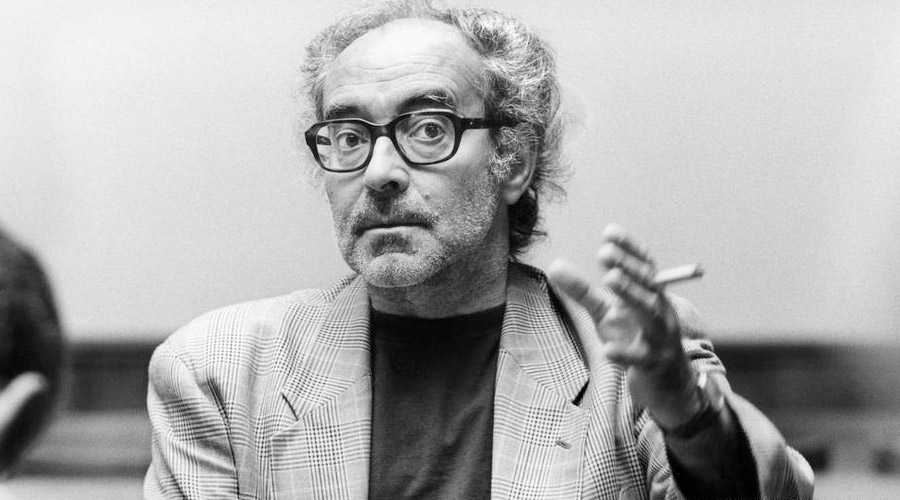

France has lost "a national treasure," said French President Emmanuel Macron. Godard was one of the most influential film directors and was often credited with revolutionizing cinema.

Franco-Swiss filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard has died at the age of 91, the French newspaper Liberation reported on Tuesday.

Godard was one of the leading figures of the movement. Critics rated him among the top 10 directors of all time, and he has had a direct influence on the likes of Quentin Tarantino, Bernardo Bertolucci, Steven Soderbergh and Martin Scorsese.

French President Emmanuel Macron said France lost "a national treasure" with Godard's death.

Interest in anthropology influenced filmmaking style

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a small group of French filmmakers turned the cinema world on its head. They called themselves the Nouvelle Vague — or New Wave — and they broke all the established rules of filmmaking.

Born in Paris on December 3, 1930, Godard moved to Switzerland with his family at age 4. For much of his youth he lived on the Swiss side of Lake Geneva, where his father, a physician, ran a clinic. He returned to Paris after the war, to complete his baccalaureate.

He studied at the University of Paris and planned to pursue a career in anthropology. Although he never completed his degree, his interest in ethnology informed his filmmaking style, as he would use documentary film techniques to create what became called "cinema verite."

His interest in films blossomed in 1950, when he joined the Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin. There he met Claude Chabrol and Francois Truffaut, who would also become influential members of the Nouvelle Vague. Initially though, his interest in films was purely as a critic. He wrote for the publication Cahiers du Cinema.

It wasn't until 1954 that he was inspired to make his first short film, while working as a laborer on the Grand Dixence dam in Switzerland. With a borrowed camera, he shot Operation Beton (1954; Operation Concrete). The construction company bought the film and used it for publicity purposes.

Breaking all the rules

A keen admirer of German playwright Bertolt Brecht, Godard wanted to translate Brecht's concept of "epic theater" into the language of film. Over the next few years, Godard, Truffaut and others worked to produce a series of short films. They developed a new take on filmmaking, using lightweight equipment, natural lighting, long takes, sometimes with improvised dialogue. The established rules of filmmaking and narrative continuity fell to the cutting room floor.

Then in 1960, Godard made his first feature film, A Bout de Souffle (Breathless). The film, produced by Francois Truffaut and starring Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo, was the turning point in his career.

A Bout de Souffle heavily referenced American film noir of the 1940s and 50s, but also combined the Nouvelle Vague's groundbreaking new techniques. The story of a car-thief who shoots a policeman and is then turned over by his girlfriend used hand-held camera work, incidental lighting, actor monologues to camera and jump-cuts.

It was the start of his most successful and influential period of filmmaking.

A new tsunami of creativity

Between 1960 to 1967 was a period of intense activity for Godard, in which he made the dozen films which form his Nouvelle Vague canon.

The most successful was the 1963 feature Le Mepris (Contempt), starring Brigitte Bardot. It was the most expensive film he made, and his only orthodox film, though it took Nouvelle Vague techniques and solidified them as the accepted way of modern cinema.

After Pierrot le Fou (1965), his second film starring Belmondo, he was asked to direct Bonnie and Clyde, but he knocked back the offer, saying he distrusted Hollywood.

Godard's political views had already appeared in films such as Le petit soldat, about the Algerian War of Independence. But in his final film in the Nouvelle Vague genre, Week-End, he delivered a scathing attack against consumerism and bourgeois society. Then in the closing credits, instead of simply "Fin," he screen lit up with "Le Fin du Cinema," or "The End of Cinema."

Political upheaval and militancy

Inspired by the May 1968 protest movement that shook Paris and other European cities, Godard became increasingly politically outspoken. With his longtime friend Francois Truffaut, he led protests that shut down the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, to show solidarity with the students and workers.

Godard's revolutionary and Marxist rhetoric pervaded both his films and his public statements. He openly criticized the Vietnam War. Between 1968 and 1973, he and Jean-Pierre Gorin made a series of films with a strong Maoist message. The best-known of them is Tout Va Bien (Just Great, 1972), starring Yves Montand and Jane Fonda. But towards the end of 1970s, Godard lost faith in his Maoist ideals.

Accusations of antisemitism

Although Godard's movie-making slowed down in the 1980s, later in life he continued to attract controversy. The Catholic Church accused him of heresy after Je Vous Salue, Marie (1985). Critics described his interpretation of Shakespeare's King Lear (1987) as "tired and labored," and "sad and embarrassing." Godard was accused of trashing his own legend.

Accusations of antisemitism dogged Godard since he traveled to the Middle East in 1970 to make a pro-Palestinian film, which he never completed; and remarks about Moses which he made on French television in 1981.

But in his book Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard, author Richard Brody argues that Godard's work treats the Holocaust with "great moral seriousness," and says that the Moses comments have been taken out of context.

His 2018 film, an avant-garde essay film called The Image Book (2018), was nominated for the Palme d'Or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. The influential director remained active into his 90s.