When the New York Philharmonic honoured the work of the film composer John Williams this past spring, the director Steven Spielberg introduced a clip of the opening scenes of Raiders of the Lost Ark — without the music. The effect, he noted apologetically, was like something out of the French new wave.

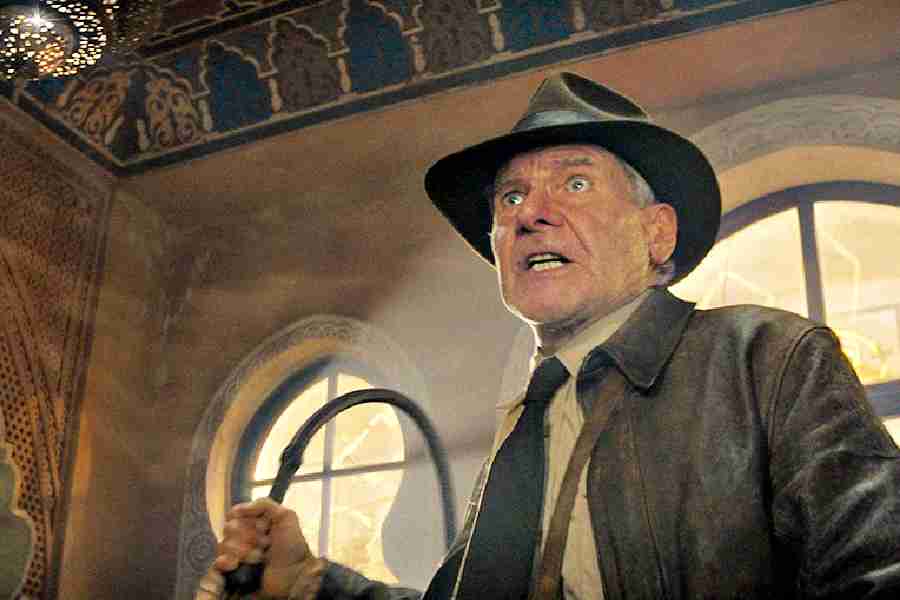

The clip was played again, this time with the orchestra joining in. Like magic, the adventuresome spirit of the movie was restored. On June 30, the rugged archaeologist at the heart of that film (played by Harrison Ford) will return for the fifth entry in the franchise, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. He’ll be accompanied, as ever, by Williams’s indispensable music.

The composer, who turned 91 this year, had said it would be his final film score. Speaking during a video call more recently, he walked back his retirement plans. “If they do an ‘Indiana Jones 6,’ I’m on board.” Ahead of the new film’s opening, Williams shared his thoughts — with contributions from others closely connected to this work — on milestone moments in an extraordinary career.

How to Steal a Million (1966)

Williams made some of his earliest contributions to movie music playing piano for the scores of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and West Side Story, among others. (That’s also him playing the chugging piano riff on the Peter Gunn theme for television.)

Under the name Johnny Williams, he gradually transitioned, as he put it, “from the piano bench to the writing desk,” composing several light, jazzy scores for comedies. How to Steal a Million, an art-heist caper starring Audrey Hepburn, was an early high point. “It was the first film I ever did for a major, super-talent director, in William Wyler,” Williams said.

With moments of comedy and tongue-in-cheek suspense, that score was an early clue of “just how versatile John Williams could be,” said Mike Matessino, a producer of numerous Williams soundtracks.

Many years later — long after his name had become synonymous with the sound of the cinematic blockbuster — Williams would channel his earlier, funnier work into the jazz-inflected score of Catch Me if You Can. That mode “had been residing there in the intervening decades, waiting to come howling to the surface,” Williams said. “It was the easiest thing in the world for me to do, and I was giggling while I was doing it.”

Images (1972) and The Long Goodbye (1973)

Working with the director Robert Altman produced a couple of the strangest entries in Williams’s filmography. The soundtrack to The Long Goodbye, Altman’s woozy neo-noir starring Elliott Gould as a laconic Philip Marlowe, consists of several cheeky variations on the title tune, including a bluesy nightclub number, a mariachi and a tango.

For the psychological horror Images, Altman gave Williams the kind of freedom he famously gave his actors. “‘Do whatever you want. Do something you haven’t done before,’” Williams remembers Altman saying.

The result was an eerie, fractured score that reflects the deteriorating mental state of the protagonist. The music was a collaboration with the Japanese percussionist Stomu Yamashta, who performed on sculptures by the artists François and Bernard Baschet. Williams said that had he devoted his career to composing for the concert hall rather than the cineplex, his work would have sounded most like his Images score.

When Spielberg was looking for menacing music to accompany scenes of dread in Jaws, he tried sounds from Images. But Williams believed the movie needed something more primal, less psychological, and eventually built a theme around two brutish bass notes.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

How to sum up the Williams-Spielberg collaboration? Beginning with The Sugarland Express and concluding (for now, at least) with The Fabelmans, the partnership has spanned 29 films.

Spielberg has described Williams’s score for Schindler’s List as “one of the most stunningly evocative gifts that John has ever given us.” It says something about the range of their collaboration that Jurassic Park came out the same year, featuring another towering Williams score — infused with an almost religious awe for the prehistoric creatures of the film.

In an interview, Emilio Audissino, the author of The Film Music of John Williams, made the case that Close Encounters of the Third Kind was the movie on which “the two fully realised the mutual advantage and compatibility of their partnership.” One moment in that film captures some of Spielberg and Williams’s alchemy: the musical dialogue between the humans and the otherworldly visitors, itself an artistic collaboration of sorts.

Williams remembers spending hours with Spielberg, listening to countless musical phrases. “We were waiting for that eureka moment.”

Many years later, Williams figured out why the phrase they ultimately chose (re, mi, do, do, so) feels so perfect. The “re, mi, do” feels musically resolved, he explained, after which “do, so” — the alien response — feels like an appropriately startling interjection. “I realised that 20 years after the fact.”

Superman (1978)

Remember when superheroes had memorable themes?

The score for Superman demonstrated one of Williams’s own musical superpowers: making the unbelievable feel thoroughly believable. His indomitable sounds are essential to audiences’ accepting — and being stirred by — the sight of a man in flight.

The director Richard Donner had a theory that the three-note motif in the main theme — the one that makes you want to punch the air in triumph — is a musical evocation of “SU-per-MAN!”

Is there anything to that? “There’s everything to that,” Williams told me.

Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace (1999)

Williams remembers feeling “a little bit insecure” on the first day of recording Star Wars in 1977. But Lionel Newman, the studio musical supervisor, “who was sitting there next to me, said, ‘This is really going to work very well — you’ll see.’”

The music for the central Star Wars saga was consistently extraordinary even when the films themselves failed to strike a chord. This is true of The Phantom Menace, which, despite its 51 per cent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, features some of the composer’s most exciting work. Today, the Carl Orff-inspired symphonic banger Duel of the Fates is the most streamed piece of Star Wars music on Spotify.

“It was pretty indescribable,” Maxine Kwok, a London Symphony Orchestra first violinist, said of the recording session. “I remember getting chills the first time the ostinato started.” Kwok joined the institution partly because she associated it with the music of Star Wars — the soundtrack to her childhood. “I grew up with those heroic trumpets and soaring strings. It had a profound effect on me.”

Scoring The Rise of Skywalker in 2019, after more than 40 years with Star Wars, Williams said he didn’t want it to be over. “My feeling was, ‘This is fun. Let’s go back and do nine more.’”

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023)

The Indiana Jones movies feature a number of Williams’s most recognisable character themes. They also feature swaths of swashbuckling music precisely calibrated to the action onscreen.

“I don’t see John as simply a genius of themes and tunes, which he is of course,” the director James Mangold said. “Rather, it’s John’s moment-to-moment scene work that astounds me. Film scoring is really a kind of duet between the director and the composer. It’s John’s sensitivity to this partnership that most defines his work for me.”

On the appeal of scoring a fifth Indiana Jones movie, Williams said, “I just thought, if Harrison Ford can do it, I can do it.” The movie features a new theme for the character of Helena, played by Phoebe Waller-Bridge. “I had a wonderful time writing a theme for her,” Williams said.

“When John first played that theme for me, with the orchestra, I was wowed, of course,” Mangold said, “completely knocked over by the music. But I was also a bit nervous that it was just too much — too damned lush. Too romantic. John just smiled, gently, and let me babble, because I think he knew it was going to work beautifully.”

Darryn King(The New York Times News Service)