Philip Norman’s aptly titled biography called him ‘the reluctant Beatles’. Those who have watched Peter Jackson’s Netflix documentary Get Back would not have failed to see what years of living in the shadows of John Lennon and Paul McCartney had done to George Harrison’s ego. Despite his immense contribution to the group, he was always considered a minor Beatle, one whose talents were rarely acknowledged. Yet, Harrison composed masterpieces like ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ and ‘Here Comes the Sun’, and his solo debut album All Things Must Pass was the best-selling solo album by an ex-Beatle and appears on many lists of the 100 best rock albums ever.

But more than all this, what’s important to note is that without George Harrison, the Beatles might never have happened. As Ty Burr notes in his review of Norman’s book, ‘The band’s earliest iteration, the Quarrymen, had broken up until George reformed them for a key club date. Their initial 1962 meeting with EMI producer George Martin was going south until Harrison broke the ice by insulting Martin’s necktie.’

George Harrison was the one who goaded the Beatles to abandon live performances and work on their sound in the studio. He became the social conscience of the world of rock music, with his Concert for Bangladesh in 1971, the all-star charity event. And above all, he was the first musician in the West to explore eastern spirituality and played an important role in creating world music, with his discipleship with Pandit Ravi Shankar. He is the one responsible for the Indian sounds that we hear in some of the band’s iconic tracks.

The Beatles’ introduction to Indian culture came through a film which, with its politically and religiously ‘improper’ content, is impossible to imagine today. Richard Lester’s Help! (1965) is a whacky, irreverential slapstick that parodies all the cultural tropes of the era. There’s something rather disconcerting in its depiction of India as a land of bloodthirsty religious cults, including the goddess ‘Kaili’ and a Swami Klang. There’s even a royal Bengal tiger that loves Beethoven’s Ode to Joy!

However, in the midst of this rather unflattering and often grotesque take on Indian customs, George Harrison discovered India through a sitar held by one of the Indian musicians playing on the set of the film. As Lennon reminisced, ‘The first time we were aware of anything Indian was when we were making the film Help!. On the set in a restaurant we had three sitars… George kept staring at them.’ Harrison added: ‘We were waiting to shoot the scene in the restaurant… there were a few Indian musicians playing in the background. I remember picking up the sitar and trying to hold it and thinking, “This is a funny sound.” It was accidental.’

That accidental encounter changed the sound of the Beatles, and indeed gave us what came to be called world music.

Across the Universe (Album: Let It Be)

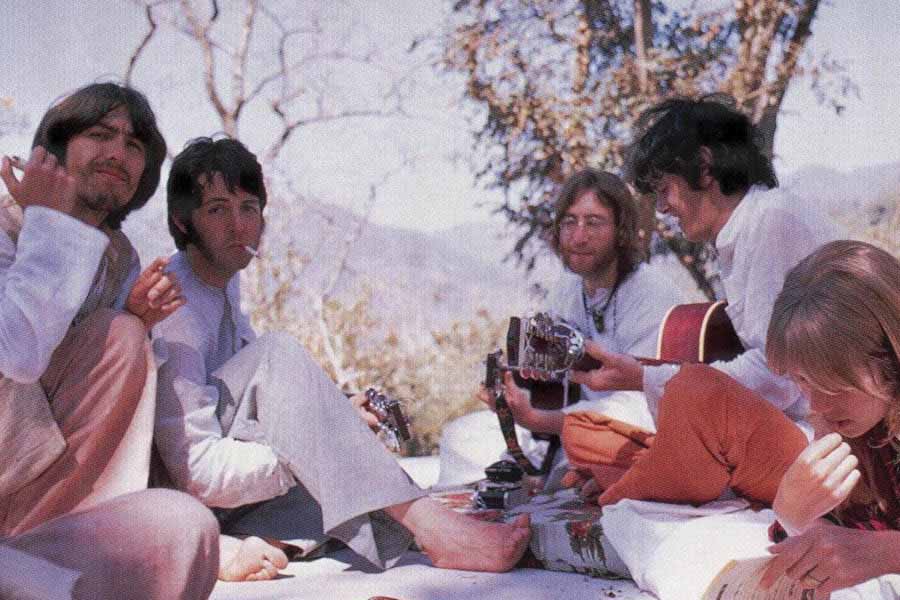

The oldest song on the Let It Be album, recorded in February 1968, which John Lennon frequently referred to as one of his favourite Beatles songs. The song was shaped by the band’s, especially George Harrison’s, interest in transcendental meditation in the late 1960s. The hypnotic phrase ‘Jai Guru Deva Om’ was added to the composition as a connection to the chorus.This phrase was commonly invoked by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in referring to his spiritual teacher.

The lyrics are image-based, consisting of philosophical concepts illustrated with phrases like thoughts that ‘meander like a restless wind’, words that ‘slither wildly’ and undying love that ‘shines like a million suns’. As he tried to sleep while arguing in bed with his wife, Cynthia, the phrase ‘pools of sorrow, waves of joy’ came to John Lennon and wouldn’t leave until he started writing.

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown) (Album: Rubber Soul)

With one of the most recognisable opening refrains in music ever, this is of course the song that introduced the sitar to the ‘rocking’ generation. It had a significant impact on the emergence of raga rock in the middle of the 1960s. Recorded in October 1965, it also assisted in making Indian classical music, especially the works of sitar maestro Ravi Shankar, well known in the West.

It was the first time the sitar had appeared on a western rock recording. Lennon wrote the song as a veiled account of an extramarital affair he had in London, and George Harrison chose to add a sitar part after becoming interested in the instrument’s exotic sound while on set of the Beatles’ film Help!, in early 1965.

Within You Without You (Album: Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band)

George Harrison became fascinated by ancient Hindu teachings after he and his wife, Pattie Boyd, visited Pandit Ravi Shankar in India in 1966. Harrison first joined other students of Ravi Shankar in Bombay, until local fans and the press learned of his arrival. Harrison, Boyd and Shankar next moved to a houseboat on Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir, where Harrison received one-on-one instruction from Shankar while studying spiritual works including Swami Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga and Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi.

Harrison composed ‘Within You Without You’ as his second piece in the Indian classical genre. Indian instruments including the sitar, tanpura, dilruba and tabla were used in the recording, which was done in London in March/April 1967. Written as a remembered conversation, this song promoted the idea that individualism is founded on an illusion created by the ego and that it promotes disharmony and division. Although the song’s point of view was inspired by Hindu teachings, it was similar to the thoughts that Lennon had previously articulated using LSD in songs like ‘The Word’, ‘Rain’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’. The phrase ‘gain the world and lose their soul’ was inspired by a warning Jesus gave which was recorded in two gospels (Matthew 16: 26, Mark 8: 36). It was one of the best expositions of the hippie mindset of the era and the song on which the group’s philosophy was stated.

Love You To (Album: Revolver)

It was the first song George Harrison wrote expressly with the sitar in mind, as the instrument was introduced to ‘Norwegian Wood’ as an afterthought. It was recorded in April 1966. Harrison had just joined the Asian Music Circle in London, which was led by musician Ayana Deva Angadi and had organised the first UK concerts for Ravi Shankar. He also included Anil Bhagwat on this recording, a tabla player whom Angadi had suggested to him. Harrison’s wife, Pattie Boyd, is the subject of some of the song’s lyrical themes but it also includes philosophical ideas influenced by experiments done with LSD.

The Inner Light (Non-album single)

Lennon and Harrison appeared as David Frost’s guests on The Frost Report, a live late-night television programme, in September 1967. This edition’s focus was Transcendental Meditation, and an interview with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was included. In the invited audience was Sanskrit scholar Juan Mascaró. Mascaró sent Harrison a letter the following month and enclosed a copy of Lamps of Fire, a compilation of spiritual knowledge from diverse traditions that he had edited. He advised Harrison to set some of the Tao Te Ching’s lyrics to music, particularly the poem ‘The Inner Light’:

Without going out of my door

I can know all things on earth

Without looking out of my window

I can know the ways of heaven.

For the farther one travels

The less one knows.

The sage therefore

Arrives without travelling,

Sees all without looking,

Does all without doing.

The song featured these lyrics and gave the band an opportunity to use Indian instruments including the sarod, shehnai and pakhawaj. Aashish Khan, Hanuman Jadev and Hariprasad Chaurasia are among the musicians on the song. It was recorded in Bombay in January 1968, making it the only Beatles studio recording to be made outside Europe. It was released as the B-side of ‘Lady Madonna’, and is the first song of Harrison’s to appear on a Beatles single.

(Shashwata Ray Chaudhuri is a student of Class XII at The Indian School, New Delhi)