Probably no other political leader anywhere in the world has been part of popular culture — films, songs, music videos, animation shows, graphic novels — as much as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Newsreels on him run into hundreds of hours. A China-based journalist, A.K. Chattier, put together one of the first celluloid versions of the Mahatma’s life and times from archival material available, sourcing rare footage. Unfortunately, both the print and the negative have been lost.

Beginning with the American feature documentary Mahatma Gandhi: Twentieth-century Prophet in 1953, to The Gandhi Murder, a conspiracy theory film on the assassination, in 2019, he has been part of at least 30 films. Even the Marvel film Age of Ultron has his footage. As many as 17 actors have played him on screen: J.S. Casshyap, Ben Kingsley, Sam Dastor, Jay Levey, Yashwant Satvik, Annu Kapur, Rajit Kapur, Mohan Gokhale, Naseeruddin Shah, Surendra Rajan, Mohan Jhangiani (voiced by Zul Vilani), Dilip Prabhavalkar, Dr Shikaripura Krishnamurthy, Avijit Datta, S. Kanagaraj, Neeraj Kabi and Jesus Sans.

Of these, Sam Dastor featured as the Mahatma in Lord Mountbatten: The Last Viceroy (1986) and Jinnah (1998), while Surendra Rajan has donned Gandhi’s garb as many as six times, in Veer Savarkar (2001), The Legend of Bhagat Singh (2002), Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero (2005), the TV movie The Last Days of the Raj (2007), the short film Gandhi: The Silent Gun (2012) and Srijit Mukherji’s Gumnaami (2019).

Gandhi and early Indian cinema

It was common in the 1930s and 1940s for film hoardings to have life-size pictures of Gandhi over the photographs of the stars. The protagonist of Kanjibhai Rathod’s mythological Bhakta Vidura (1921), the first film to be banned in India, resembled Gandhi, cap and all. Ajanta Cinetone’s Mazdoor (1934), written by Munshi Premchand, too, was banned, and promoted as ‘the banned film’, as it dealt with Gandhian principles. Produced by Imperial Film Company and directed by R.S. Chaudhary, Wrath (1931) had a character called Garibdas who fights untouchability. The censors cut out many of its scenes and renamed it Khuda Ki Shaan. Vinayak Damodar Karnataki’s Brandy Ki Botal (1939) took up Bapu’s campaign against liquor and referred to Gandhi as ‘azadi ka devta’.

The feature biopics

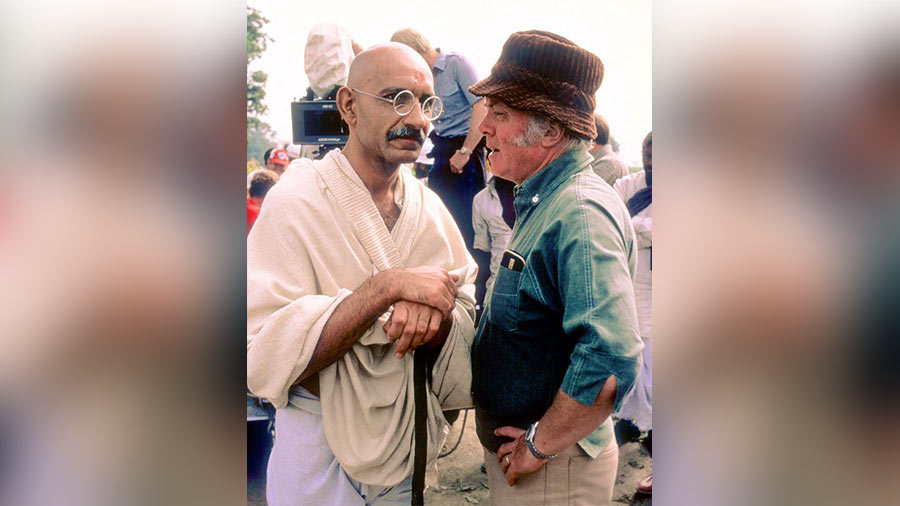

The most well-known of these is Richard Attenborough’s 1982 film. In the making for over 20 years, Attenborough’s Gandhi remains, warts and all, the definitive film on Gandhi. And though Attenborough made the cardinal error of falling prey to what Nehru had warned him against at the outset when the director had met him with the proposal in 1963 — “Whatever you do, do not deify him… that is what we have done in India… and he was too great a man to be deified” — there is no doubt that this is an epic labour of love that delivers a series of spectacular setpieces of great emotional heft.

The filmmaker himself observed, “It took me 20 years to get the money to get that movie made. I remember my pitch to 20th Century Fox. The guy said: ‘Dickie, it’s sweet of you to come here. You’re obviously obsessed. But who the f***ing hell will be interested in a little brown man wrapped in a sheet carrying a beanpole?” As it turned out, the whole world was, as was the Oscar committee. And Ben Kingsley set a benchmark for the onscreen Gandhi that has been impossible to top over 40 years later. So complete was the identification that a few years later a popular Hindi film, Peechha Karro (directed by Pankaj Parashar, 1986), had a character swear by Ben Kingsley instead of Gandhi.

Surprisingly, despite the many incarnations of the Mahatma in cinema, Gandhi is only one of two full-length feature films to deal with his life. The other one being Shyam Benegal’s The Making of the Mahatma (with Rajit Kapoor essaying the role), which, as its Hindi title, Gandhi Se Mahatma Tak, suggests, deals primarily with his experiences as a barrister and in South Africa. Several biopics on national leaders of the freedom movement feature Gandhi in important cameos. These include Sardar (d: Ketan Mehta, 1993, Annu Kapoor as Gandhi) and Jabbar Patel’s Dr B.R. Ambedkar (2000, with Mohan Gokhale as Gandhi), probably the first time the Mahatma was shown in a negative light. There was also the 2011 film Dear Friend Hitler, based on his correspondences with Adolf Hitler (played by Raghubir Yadav).

These biographical films include Gandhi, My Father, which deals with his tortured and tumultuous relationship with his son, Harilal Gandhi. Based on the latter’s biography Harilal Gandhi: A Life by Chandulal Bhagubhai Dalal, the film was directed by Feroz Abbas Khan, who had earlier helmed a stage version, Mahatma Vs Gandhi (based on Dinkar Joshi’s Gujarati novel Prakashno Padchhayo), starring Naseeruddin Shah and Kay Kay Menon as Gandhi and Hiralal respectively. The film version starred Darshan Jariwala and Akshaye Khanna as father and son.

The adversarial gaze

Existing with the eulogies are a handful of films that portray the world of his adversaries — people like Nathuram Godse and Veer Savarkar, in particular. Unfortunately, none of these have the rigour of the works of Richard Attenborough and Shyam Benegal, and have been rightly dismissed as sensationalist. Ashok Tyagi’s 2017 short film Why I Killed Gandhi, which released in early 2022, became controversial for allegedly showing Godse as a hero, forcing its lead actor to apologise for playing the role of Godse. In the same vein is Ved Rahi’s Veer Savarkar (2001). Kamal Haasan’s Hey Ram (2000), a fictional tale of the moral dilemmas facing a would-be assassin of Gandhi, is in comparison a more nuanced take, though Naseeruddin Shah is probably the healthiest Gandhi onscreen ever.

But by far the more interesting fiction came close to 60 years ago. In 1963, around the time that Attenborough was talking to Pandit Nehru about his film on Gandhi, Nine Hours to Rama created quite a flutter for its purportedly “sympathetic” take on Nathuram Godse. Narrating the last nine hours of the life of Gandhi’s assassin, this one is a strange beast. Dismissed by academic Ravinder Singh as “a heady concoction of a little history and too much fiction”, the film shows Godse involved in an affair with a married woman and even an encounter with a prostitute. It faced protests from both Congress and Godse’s supporters and an eventual ban.

A laughable enterprise in all respects — the only thing it probably gets right are the three bullets, and even that scene is followed by a ridiculous one where Gandhi forgives Godse who is shown as repenting his act immediately afterwards — what is surprising about it are the credentials of the people involved with the project. The director Mark Robson is well known for Hollywood blockbusters like The Bridges of Toko Ri, The Harder They Hall, Peyton Place and Von Ryan’s Express. The screenwriter Nelson Gidding scripted critically acclaimed ones like The Haunting and Andromeda Strain. And among the cast, we have respected actors such as Jose Ferrer (who essayed the definitive Cyrano de Bergerac on stage and screen) and Robert Morley.

What makes this somewhat of a curio are the smattering of Indian actors in cameos, including David as a policeman, Achala Sachdeva (as Godse’s mother) and P. Jairaj as G.D. Birla. By far the most interesting and innovative aspect of the film is its credit titles — comprising the ticking of an old-fashioned pocket watch — designed by Saul Bass, which is deserving of a full-length article.

The shadow of Gandhi: Gandhigiri

Gandhi’s life and philosophy have cast long shadows, particularly in Hindi cinema. Almost all films that show a police station invariably have his photograph up there on the wall as part of the background decor. However, it is in the subtle messaging of Hindi cinema that his influence is most strongly felt, particularly the way our films have for the longest time made a virtue of being poor, equating money with all evil.

Possibly the one film that epitomises the enduring legacy of the Mahatma and was instrumental in reintroducing him in popular discourse is Rajkumar Hirani’s Lage Raho Munna Bhai (2006). In a stroke of genius, the film’s makers have a goonda hallucinating about the Mahatma, who inspires him to “Gandhigiri” (the term caught on in a big way, leading to a 2016 film starring Om Puri, titled Gandhigiri) instead of gundagiri as a tool to get your way.

Though not as influential as the Munna Bhai film, Jahnu Barua’s Maine Gandhi Ko Nahin Mara (2005) is as important. The film, about a retired professor whose dementia-wasted mind begins to believe that he was accused of killing Gandhi, is a metaphoric exposition of what Gandhi and the values he espoused mean today, how he has been reduced to a statute, a road and a stamp. If Munna Bhai has the two goondas recalling Gandhi only from his photo on currency notes and on account of October 2 being a dry day, Barua’s film highlights how we remember the man only on two days — October 2 and January 30.

Gandhi’s influence on the national psyche has been part of many other films tangentially. The 2009 film Road to Sangam is the story of a Muslim mechanic entrusted with the job of repairing an old V8 ford engine, little knowing that the car had once carried Gandhi’s ashes to the Sangam for immersion. While Shah Rukh Khan’s character in Swades is named Mohan, and the film, according to Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson Tushar Gandhi, “epitomises Gandhi’s values”, A. Balakrishnan’s Welcome Back Gandhi (2012) imagines the leader returning to contemporary India and dealing with a country he barely recognises.

Girish Kasaravalli’s Koormavatara (2011) tells the story of a government employee who is selected to portray Gandhi in a TV series, owing to his strong resemblance to the leader. Having never acted before and not a believer in Gandhian principles, he resists before reluctantly taking up the assignment. Reading on Gandhi and his philosophies transforms his life as people start flocking to him and he must negotiate the tricky terrain of being regarded as a modern-day Gandhi.

Different strokes: Rapping with Martin Luther King to stand-up comedy

Imagine Gandhi and civil rights champion Martin Luther King Jr. engaged in a battle of rap! That is exactly what Keegan Michael Key and Jordan Peele did in the popular web series Key and Peele, which has Gandhi and King going the hip-hop way to decide who is the better pacifist.

While the inspiration behind the name of the Canadian punk rock band, Propagandhi, is not hard to ascertain, the animated TV series Clone High, made by Phil Lord, Christopher Miller and Bill Lawrence, imagined teenage versions of legends, among them Gandhi, who is shown as a ‘fun-loving, hyperactive teenage slacker’. In the TV series Family Guy, Gandhi shows up as a stand-up comedian while South Park has a character meeting Gandhi in hell.

Following in the footsteps of Mahatma Vs Gandhi and Lillete Dubey’s Sammy, from Pratap Sharma’s play (the title derived from the word ‘swami’ which was used by South African whites as a demeaning term for Indian workers), Danesh Khambata went the Broadway-style musical way with his theatrical production, Gandhi: The Musical. The play covers the leader’s life through 16 songs and a dozen dances, featuring a cast of over 40 dancers, introducing song-and-dance routines into the Mahatma’s life.

The impact that playing Gandhi has on an actor and the process that it involves also need to be explored at greater length as it provides insights on how influential he continues to be. Joy Sengupta, who portrayed Gandhi in Sammy, says, “It changed my perspective in life. I was all revolutionary and fashionably loathing Gandhi. I had even directed a play on Bhagat Singh, taking pot-shots at Gandhi. Sohail Hashmi told me not to do that, as Gandhi was the only and the most powerful secular symbol surviving in India. That kind of opened a few clogs in my head regarding what secularism is, whether it could coexist with spiritualism, among others. Ten years later, Sammy happened.”

“I gave up all mainstream work for four months to focus on the play. I went to every Gandhi institution I could, pored over every photograph to imbibe the body language, every film division reel to get his body rhythm. Recording of his speeches gave me his intonation and pitch. I switched to a Gandhian diet and lost 12 kg. I travelled by local transport. I took in all the hardships and drew strength from the Gandhian perspective of using your negatives by turning them into your strengths. This is something I had read when I was a kid in a school textbook, and it had remained with me. Now it became my full-blown philosophy – hardships and punishment can go on to make you a better man,” he recalls.

“I did not go for any complicated process – Gandhi believed in simplicity and executed everything in its simple organic form (something the intellectual Nehru found difficult to understand). It was simple. Be transparent, rely on truth, accept faults and do penance, forgive others, do it yourself, and always look at the poorest and most vulnerable as a consequence of your actions. Most importantly, listen to your inner voice for guidance. If you really mix all that, you get a simple childlike man who was always busy doing simple things to improve his inner being. I aimed for his essence, focusing on catching his spirit on stage and not mimicking him,” the actor adds.

Songs eulogising Gandhi are dime a dozen in India, of course. These include the reverential non-film ‘Suno-suno ae duniya waalon Bapu ki ye amar kahani’ (Mohammad Rafi) and ‘Gundham hamare Gandhiji’ (S.D Burman).

While the celebrated De di hame azadi bina khadag bina dhal, Sabarmati ke sant tune kar diya kamal (Jagriti, 1953) spoke of Gandhi as someone to look up to, to emulate, Lage Raho Munna Bhai’s sensational Bande mein tha dum made Gandhi cool, a buddy you can count on when in trouble, giving us a Gandhi for Generation Z.