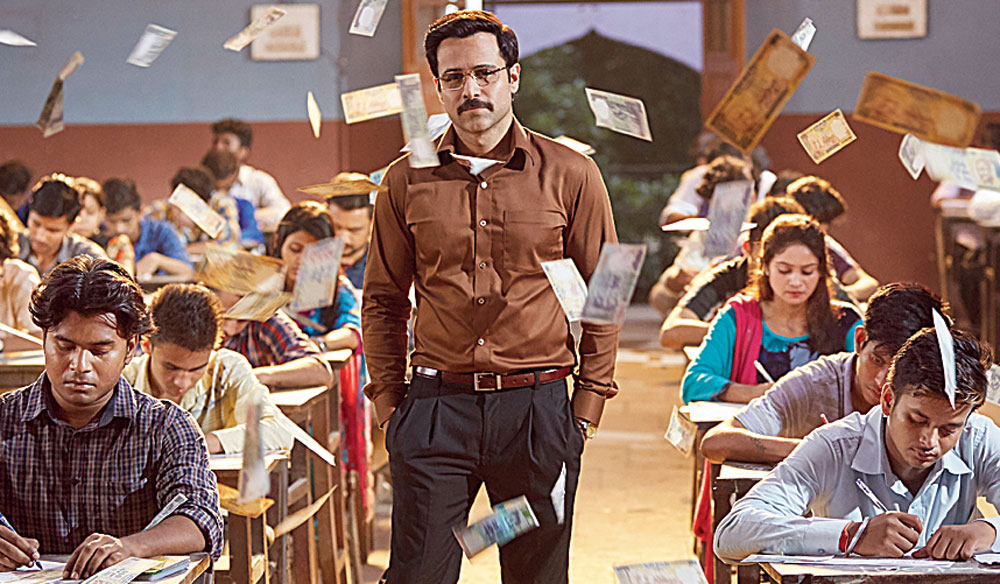

Because Rakesh is played by Emraan Hashmi, he’s also known as Rocky and often breaks into romantic songs that are more suited to a Bhatt film. And he kisses!

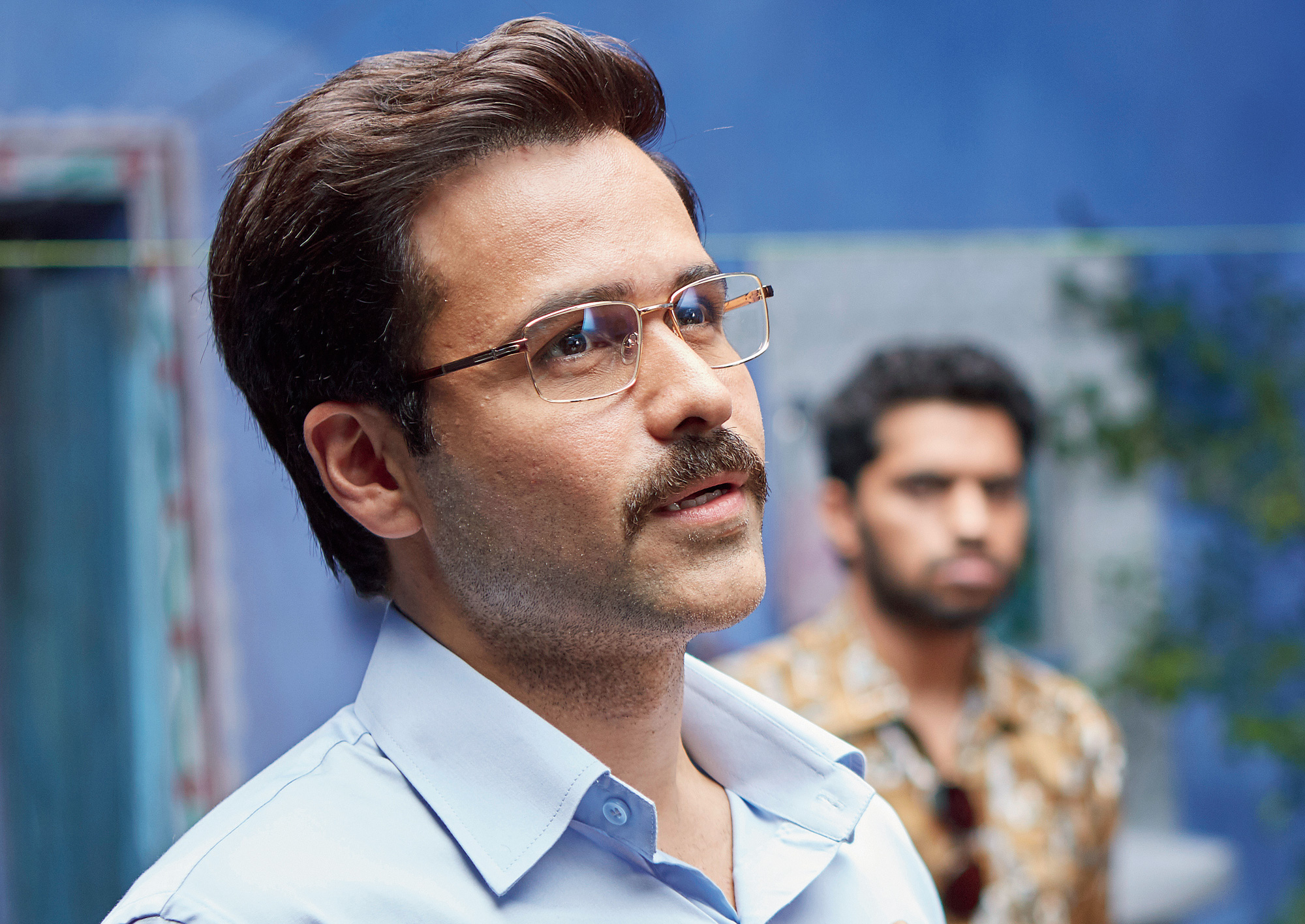

The biggest problem with Why Cheat India is that it cannot decide whether to project its protagonist as a hero or a villain. Rakesh launches a series of scams, but whenever he’s caught, he starts spouting long lectures on how he’s a Robin Hood-style character who is on a mission to cleanse the system. He pushes students into amoral practices, but his eyes well up every time he hears about a young life that falls prey to suicide. He may be morally corrupt but because he’s a Bollywood hero, this is a man with a conscience.

Why Cheat India is as confused as its protagonist. The disclaimer at the beginning describes it as “a hybrid of fact and fiction”. The film starts off well with familiar scenes of frenzied exam centres, coaching institutes duping students with the promise of guaranteed good results and young minds struggling to cope with the pressure of parents’ expectations. But what could have been a comprehensive look at the perils and pitfalls of the examination system becomes a superficial film about the mind and messy methods of its central character.

Calcutta boy Soumik Sen — who made his Bolly debut with the Madhuri Dixit-Juhi Chawla she-film Gulaab Gang and is in the director’s chair here — has an interesting idea to play with, but he fails to convert Why Cheat India from a promising one-line idea to a compelling two-hour film.

To be fair, the first half, powered by Emraan’s slickly acted artful dodger, is interesting in parts. It focuses on 18-year-old Satyendra Dubey (Snigdhadeep Chatterjee) who aces his engineering exam and becomes the hero of his native town Jaunpur by landing a plum seat in a prestigious college, but finds himself squandering it all when he takes up Rakesh’s offer of making a quick buck by writing exams for others.

Young Snigdhadeep’s wide-eyed performance helps to lift the film, but Sen wastes too much time in inane subplots and peoples his films with too many characters. Faces flit in and out of the film — all linked to Rakesh in some way or the other — with the plot failing to justify the presence of most of them.

The second half is a mess, and a twist at the tail does nothing to redeem the film. It doesn’t help that none of the side players — with the exception of debutante Shreya Dhanwanthary who shows promise despite a sketchy part — make much of an impact.

From the iconic Gordon Gekko line “Greed is good” to a poster of Satyajit Ray’s Jana Aranya — a film about a young man who resorts to malpractices after failing to find a job — the references are many in Why Cheat India. There’s a Breaking Bad-style scene featuring a room filled with cash from floor to ceiling and the film even quotes astrophysicist and author Neil deGrasse Tyson on the compelling reason that makes students cheat.

Why Cheat India ends with some powerful statistics — ranging from how only seven per cent of Indian college graduates are employable to the business of coaching institutes, at last count, being worth a staggering Rs 45,000 crore. There’s a story to be told here. Sadly,this film fails to tell it.

The existential crisis in Why Cheat India is not limited to its title. There is no clear reason why this film exists, what it wants to say and how it wants to project its central character.

Rakesh Singh is the man in the middle, a street-smart smooth operator who rebels against the system of examinations and learning by rote by putting his weight behind a scam that makes intelligent students proxy-write competitive entrance exams for the sons of rich fathers.

It’s a win-win situation for both parties with one making enough money to fund their own studies and the other securing seats in prime engineering institutes without lifting a finger.